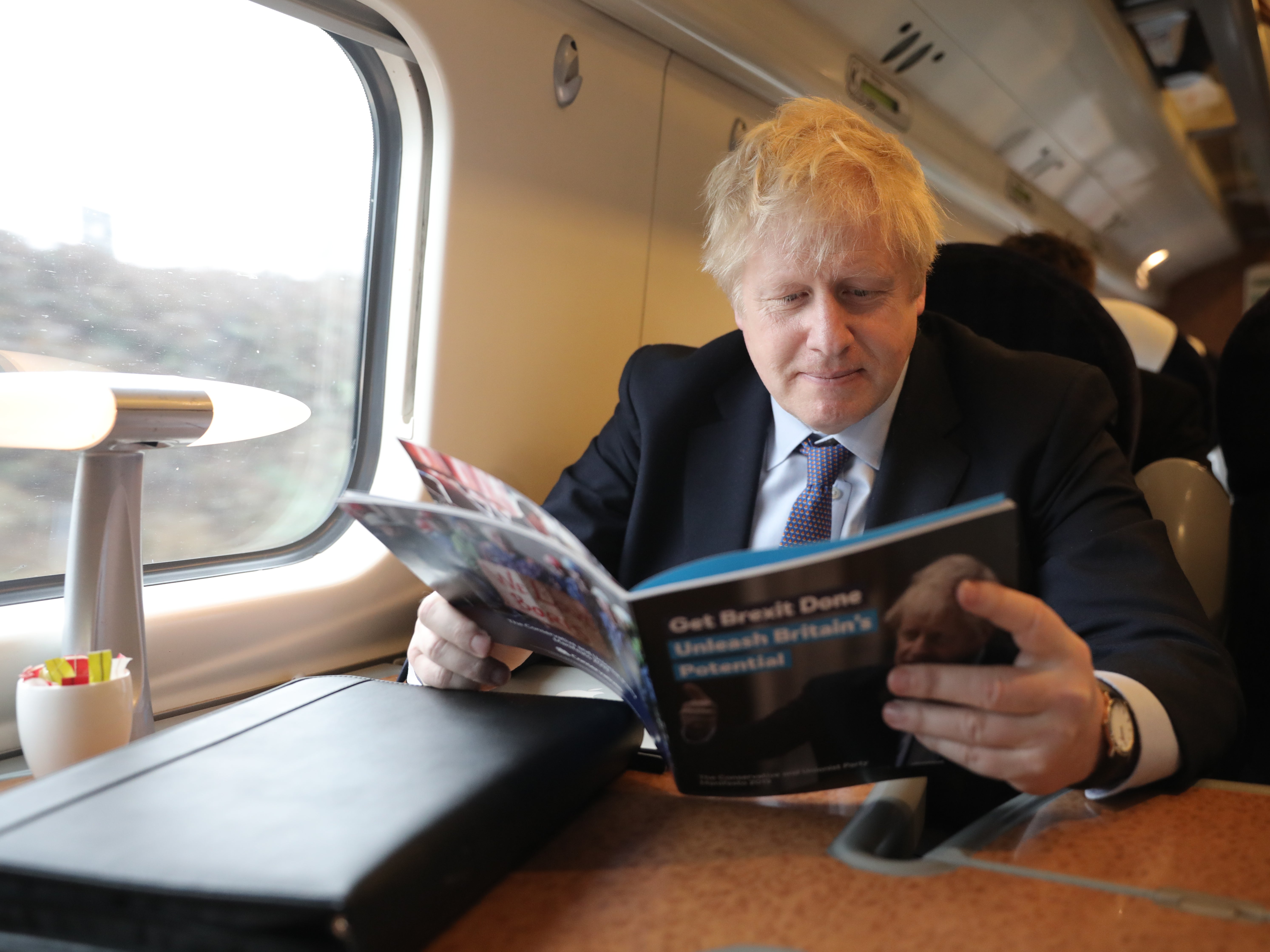

Can Boris Johnson make the trains run on time?

It is a moment of redemption for rail, writes Sean O’Grady, but there is a long way to go before it can be considered a success

Despite the Awdryesque name, Great British Railways cannot but be an improvement on the various flawed structures that have tried and failed since the old fully integrated British Rail was broken up and privatised a quarter of a century ago. The only pity is that it has taken so long for successive governments of all three national parties to finally realise that the old model was as obsolescent as a steam locomotive, but with none of the charm.

For far too long consumers, business and leisure users of the rail network have had to put up with satirically high fare and carriages as overcrowded as anything in Europe. Jam-packed and expensive, the railways were carrying record numbers of passengers despite rather than because of the way they were run. It is fair to say that privatisation has, broadly, brought greater investment and innovation, and a tiny element of increased competition, but the everyday experience of the users was disappointing to say the least.

This was especially true in the north of England, where ancient bus-based trains ran to increasingly chaotic timetabling. Against its older prejudices – in its day British Rail was a national joke – the public gradually came to reconsider its view of public ownership, and the private sector has been put in its rightful place. Labour, under Jeremy Corbyn added to that pressure for reform, and Boris Johnson, who cares little for ideology, has gone with the grain of public sentiment.

Bringing in a more integrated, state-led, concession-based system was a natural move for a former mayor of London, where Transport for London takes responsibility for setting fares, regulating service levels and the infrastructure across all public transport. In future, the private train operating companies will be given a fee for operating a defined service to certain standards of safety, security and cleanliness – and that is all.

Welcome as the reforms are, the dangers can already be glimpsed. Having lost their power to set off-peak fares, which were often ridiculously high, and with certain minimum service standards, the train operators will look to cutting operating costs as a way of maximising the profitability of their passenger operations. Those working for the different rail operating companies will, then, face downward pressure on wage rates and more redundancies in the coming years.

The vexed question of the role of guards, for example, will be revisited, and Great British Railways, part-nationalised industry, part regulator, will need to make sure that safety is not compromised in the process. More positively, the Great British Railways of the future will, or should, be able to reap, the benefits of the new technologies in everything from flexible ticketing, to integration of bus and rail services, to “driverless” trains. The railways haven’t been seen as a force for technological innovation since electrification.

The once comprehensive Victorian network that touched virtually every hamlet and village was starved of investment, bankrupt and worn out at the end of the Second World War, and cut back under the long period of nationalisation afterwards. Now lines made redundant in the Beeching-era are being restored, and the opportunity is there for rail services across England, at any rate, to be “levelled up”. After all, it did all begin with a journey from Stockton to Darlington.

It is a moment of redemption for rail, not least for the part public transport can play in keeping greenhouse gas emissions down and slowing climate change. The original sin committed at nationalisation, the split between the infrastructure – rail, signalling and main stations – and the operation of the train services themselves – has been redeemed.

It has been coming down the line ever since the private sector custodians of the infrastructure, Railtrack plc, went bust in 2002, but governments of every party have previously failed to find a way to get the best out of the private sector in delivering a vital public service. Against all expectations, will future generations be able to say of Boris Johnson that at least he made the trains run on time?

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments