Tony Blair, Margaret Thatcher and why parties always turn on long-suffering PMs

As the former prime minister says he left office at his least popular, Sean O’Grady looks at why leaders get no thanks from the parties whose fortunes they have transformed

Despite appearances – toothy grin, leaping on to planes to sunny summits, doing comedy vids with Catherine Tate – it turns out that Tony Blair wasn’t living the dream during his 10 years as prime minister after all. Now he tells us!

According to the man the Tories enviously knew and studied as “The Master”, and who dominated the political stage for so long: “I don’t think I did enjoy the job because the responsibility is so huge ... Every day you’re making decisions and every day you’re under massive scrutiny, as is your family. So I didn’t know if I enjoyed it.”

Actually he also always used to say that he hated being leader of the opposition, so Blair’s personal odyssey of pain goes all the way back to 1994. Maybe he wants compensation for hurt feelings and loss of earnings (compared to what he might have got as a barrister, though it’d be hard to press that case too far, given his proven money-spinning abilities since he quit Downing Street in 2007).

Thoughtful as ever, Blair offers us this typically incisive insight: “The paradox is that you start at your most popular and least capable and you end at your least popular and most capable.”

You can see what he means. When he became Labour leader, the Tories’ spin doctors attempted to portray him as “Bambi”, a sort of soft, doe-eyed idealist, believe it or not, totally unprepared to take the sort of tough decisions required in government. Not like John Major. Oh yes! A decade and half later, and a pile of bodies left behind in Iraq, and Blair was nobody’s idea of Bambi. Millions poured through the streets of London to protest the “illegal” wars in the Middle East, and a few years later (albeit having delivered a historic third Labour majority government in the meantime), his own chancellor and MPs forced him out of office. During the Corbyn era he was lucky not to be sent by his own party to The Hague as a war criminal. No doubt some sentimental socialists still have their Stop the War Coalition “Bliar” placards as souvenirs of the misery of life under the New Labour government. It might be some comfort to them that Tony wasn’t having much fun bombing Baghdad. Having his wife, Cherie, routinely referred to as the “Wicked Witch” in certain newspapers can’t have been comfortable for him, either.

The trajectory Blair describes is indeed a familiar one for prime ministers. Very few get to go at a time of their choosing and in a manner of their own choosing. Ask Theresa May about that. Gordon Brown rescued the world economy when he saved the banks, but got no thanks.

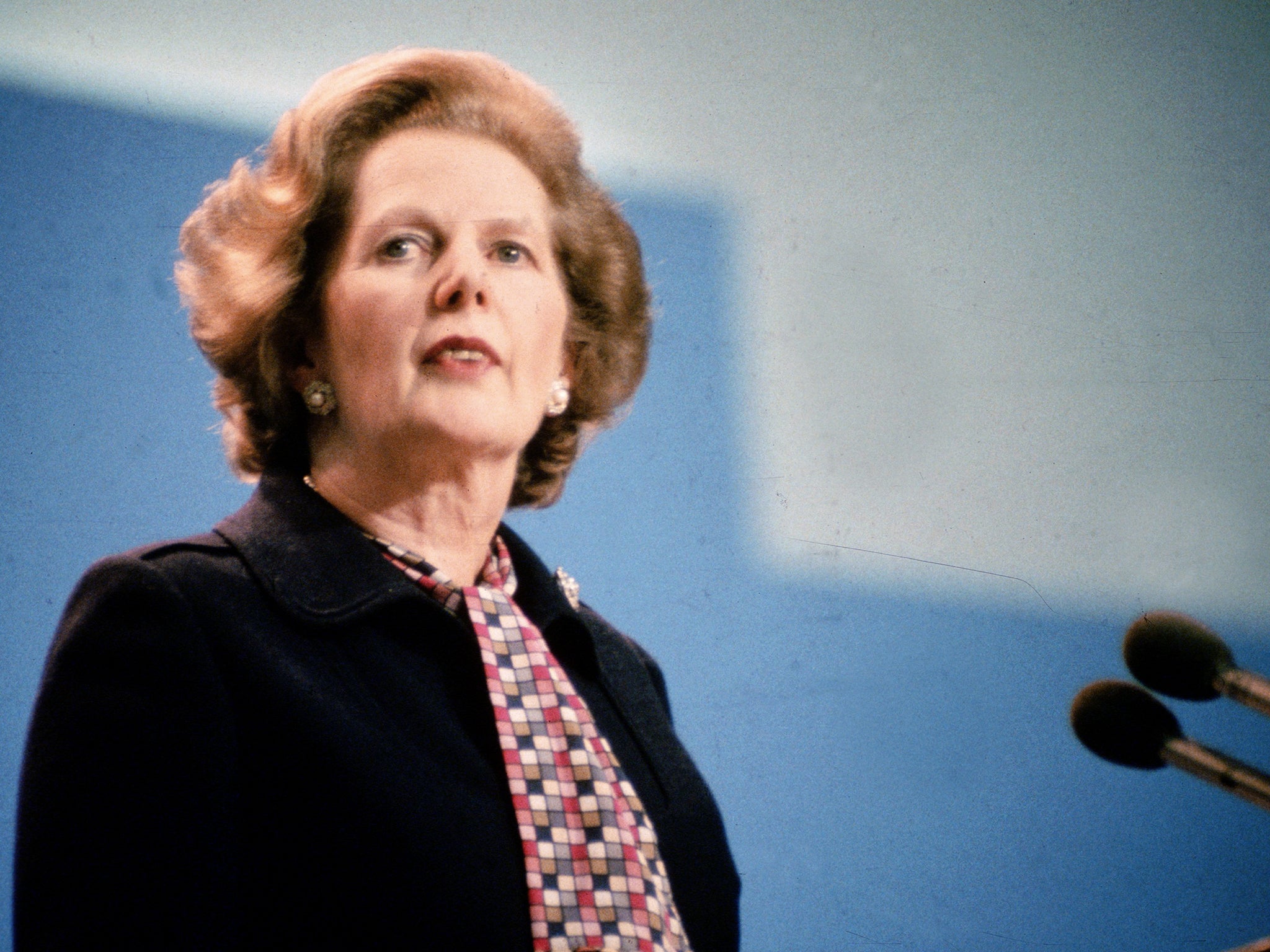

The Blair story echoes most closely that of Margaret Thatcher. She, too, was at the peak of her powers, a truly global player, when her cabinet committed its act of regicide in 1990, famously remembered by her as “treachery with a smile on its face”. Like Blair, she had performed electoral wonders for her formerly demoralised party, strengthened a special relationship with America, and presided over economic progress and social reforms that changed the face of the nation. Both ended up hated for their efforts, by their supposed friends as well as their enemies. Both were followed by “fag end” anticlimactic premiers, John Major and Gordon Brown respectively, who seemed to have been put on God’s earth to prove the force of the old adage “be careful what you wish for”. As the Iron Lady remarked, “it’s a funny old world.”

Yet perhaps old Blair is still spinning us a line. No doubt his skills as a statesman in war and peace had been transformed by 2007. They could scarce not be. As he admits, rather endearingly: “The first job I ever had in government was prime minister. I use the analogy of a football team. If you're looking for the new coach of Manchester United and [say], ‘I tell you what, we’re going to find the most enthusiastic and persuasive fan we can find and put him in charge of the team,’ people would say you’re insane.”

Yet by the end, it was he whom his colleagues thought was a bit insane, and increasingly out of touch with the party, the country, or even reality (just as Thatcher’s critics said she was “off her trolley”). After a decade in power, its confident exercise does become second nature, true, but it can also deteriorate into a kind of manic belief in your own infallibility. The manifestations of this mania include a refusal to listen to critics, friendly or otherwise, a reluctance to accept that anyone around the patient could possibly be a worthy successor, and a slight bulging of the eye when irritated.

Blair may also, conversely, be overstating his unpopularity. He was certainly unloved by the left, even after all he had done for public services and civil rights, but with the public? It is not so obvious. Might he have won a fourth term and beaten David Cameron’s Tories if he’d faced the rebels down and somehow hung on through the financial crisis to the 2010 general election? It’s not impossible to imagine that he’d have had more chance of seeing off the Tory challenge, which wasn’t even powerful enough to give Cameron a majority. Surely seeing Cameron carry the can for a fourth Tory defeat would have given Tony at least a bit of job satisfaction? With a strong economic recovery thereafter, Blair, still a young man, could have won again in 2015. He might still be with us today in No 10, and Brexit would never have happened and Johnson would still be writing puerile columns and running after attractive American infopreneurs. It might not have made Blair happy, but it might have cheered some of us up.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments