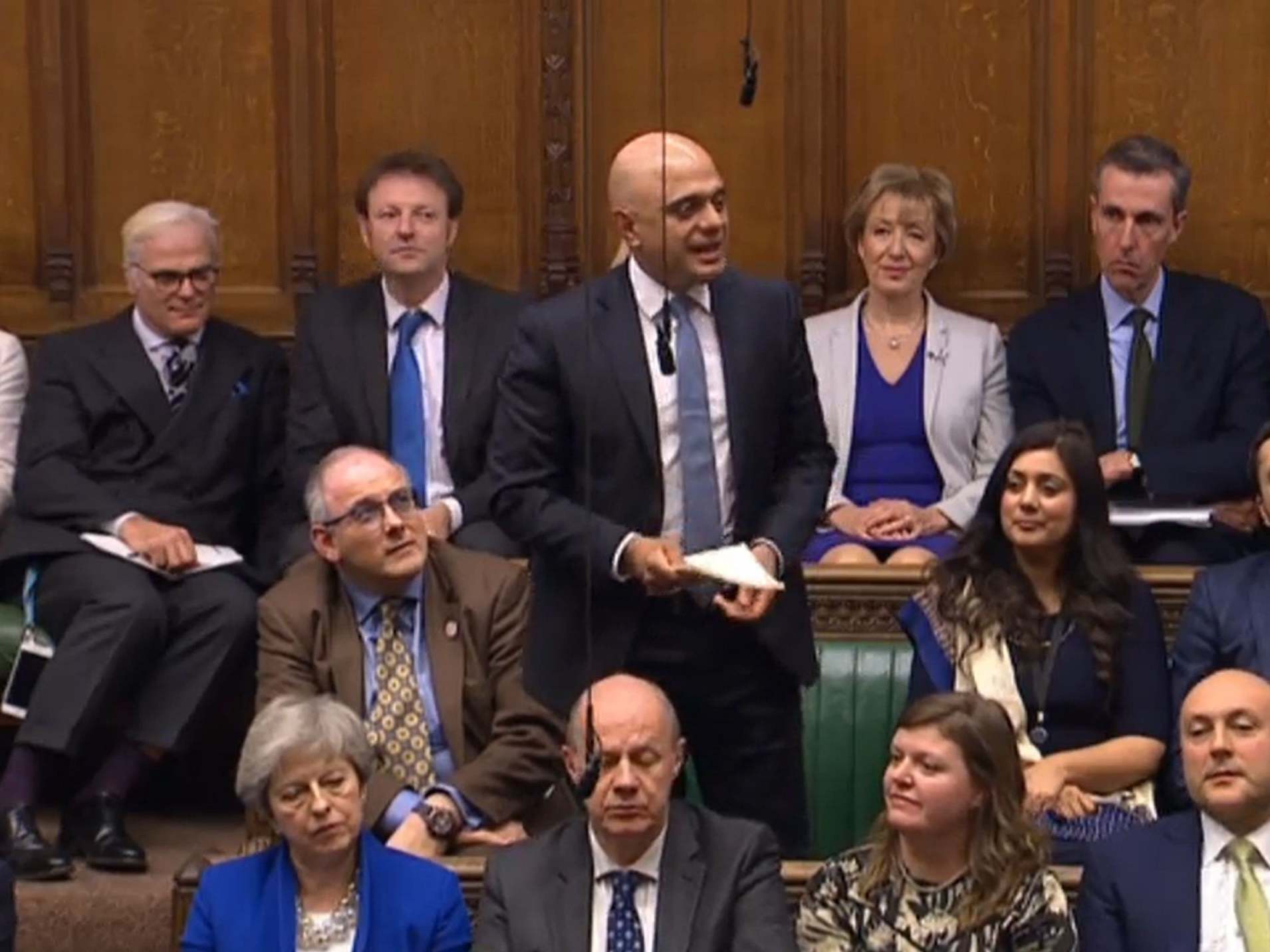

Where does Sajid Javid’s resignation statement rank in Commons history?

From Geoffrey Howe to Robin Cook, ministers have used their return to the back benches to inflict political injury on their former bosses, says Sean O'Grady

When a minister resigns – or, more often, to save blushes, is asked to resign – from the government, they have a traditional chance to make a “personal statement” to the House of Commons (granted at the speaker’s discretion). It is supposed to be heard in silence, and not be interrupted. It is “personal” in the sense that the individual is now a backbencher, and not speaking on behalf of the government. It is also “personal” in the sense that the vengeful invective can be so personal to the prime minister who fired them that it does immediate and lasting damage to their careers.

Some, like Geoffrey Howe’s fatal assault on Margaret Thatcher in 1990 (he was her deputy prime minister), can change the course of history and bring about the end of an era. Howe’s remarks were supposedly framed by his wife, Elspeth, who had even less time for Maggie, not least because she bullied Geoffrey. In any case the speech drew a laugh and then gasps of astonishment in quick succession before he sat down:

“It’s rather like sending our opening batsmen to the crease only for them to find that, before the first ball is bowled, their bats have been broken by the team captain,” said Howe. “The time has come for others to consider their own response to the tragic conflict of loyalties with which I have myself wrestled for perhaps too long.” Thatcher, prime minister for 11 years and undefeated in three general elections, was out within a fortnight, the process having been started about a year before, as it happens, by a personal statement from another ex-chancellor, Nigel Lawson.

When Boris Johnson quit as Theresa May’s foreign secretary in 2018, and complained about “dither and delay”, he knew exactly what he was doing, and it was probably the key moment in her demise. The same goes for Norman Lamont, John Major’s chancellor, when he told MPs that the embattled government led by his “right honourable friend” was “in office but not in power”.

Sajid Javid’s statement ranks below those on the Richter scale. Yet even the most vicious attack on Johnson wouldn’t bring him down, having just won a near-landslide at the December election, delivered Brexit and seen off Jeremy Corbyn, as promised. On the other hand Javid’s thinly veiled warnings about the erosion of Treasury power, the reckless power wielded by Dominic Cummings and the prime minister’s indifference to the national debt will certainly have struck a chord with even loyal Tory backbenchers. In mentioning ominously, in passing, that he did not feel his own time in public life was over, Javid left open the possibility of making some more trouble for Johnson and Cummings in future. They have plainly made an enemy, and one biding his time.

Most “personal statements”, sad to relate, are long forgotten. Not every sacked minister takes the opportunity to make a statement anyway; some have nothing much worth saying; others do let off a bit of steam, much to the delight of the “bubble” around Westminster, and provide some handy, if ephemeral, copy for political journalists. Even in such cases the fuss is usually short-lived, the dogs bark for a bit and the caravan moves on. This is especially the case if the prime minister has won an election or is enjoying broad support in their party or the country – as Johnson has.

It is difficult to recall a single ministerial resignation from the Blair government, for example, that made much difference to anything – with one striking exception. When the late Robin Cook left the cabinet in 2003 over the war in Iraq, his powerful, reasoned arguments damaged the government’s integrity, and have haunted Blair ever since. They were made all the more effective by his stating at the outset that “the present prime minister is the most successful leader of the Labour party in my lifetime. I hope that he will continue to be the leader of our party, and I hope that he will continue to be successful. I have no sympathy with, and I will give no comfort to, those who want to use this crisis to displace him.”

Cook, arguably the finest speaker of his generation, was prescient, and his words are worth recalling as we deal with consequences of the war, nearly two decades on: “On Iraq, I believe that the prevailing mood of the British people is sound. They do not doubt that Saddam is a brutal dictator, but they are not persuaded that he is a clear and present danger to Britain. They want inspections to be given a chance, and they suspect that they are being pushed too quickly into conflict by a US administration with an agenda of its own. Above all, they are uneasy at Britain going out on a limb on a military adventure without a broader international coalition and against the hostility of many of our traditional allies.

“From the start of the present crisis, I have insisted, as leader of the house, on the right of this place to vote on whether Britain should go to war. It has been a favourite theme of commentators that this house no longer occupies a central role in British politics. Nothing could better demonstrate that they are wrong than for this house to stop the commitment of troops in a war that has neither international agreement nor domestic support. I intend to join those tomorrow night who will vote against military action now. It is for that reason, and for that reason alone, and with a heavy heart, that I resign from the government.”

For that Cook won applause, a rarer event in the Commons then than now.

There have of course been other notable personal statements. In 1993 Michael Mates was a junior minister who quit over his links with disgraced businessman Asil Nadir, and who was interrupted by the speaker herself, Betty Boothroyd, who felt he had strayed into areas that might come up in a subsequent trial. The famous personal statement by John Profumo in 1963, albeit when still a minster, that “there was no impropriety whatsoever in my acquaintanceship with Miss Keeler”, was the beginning of the end for his political career and for the Macmillan government too.

Like the curious personalities who populate politics, the personal statement is as variously dramatic, dull, self-serving, heroic, statesmanlike, foolish, game-changing, irrelevant, bold, mendacious, truth-to-power or funny as they are. Javid fits nicely into the long tradition. We have not heard the last from him.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments