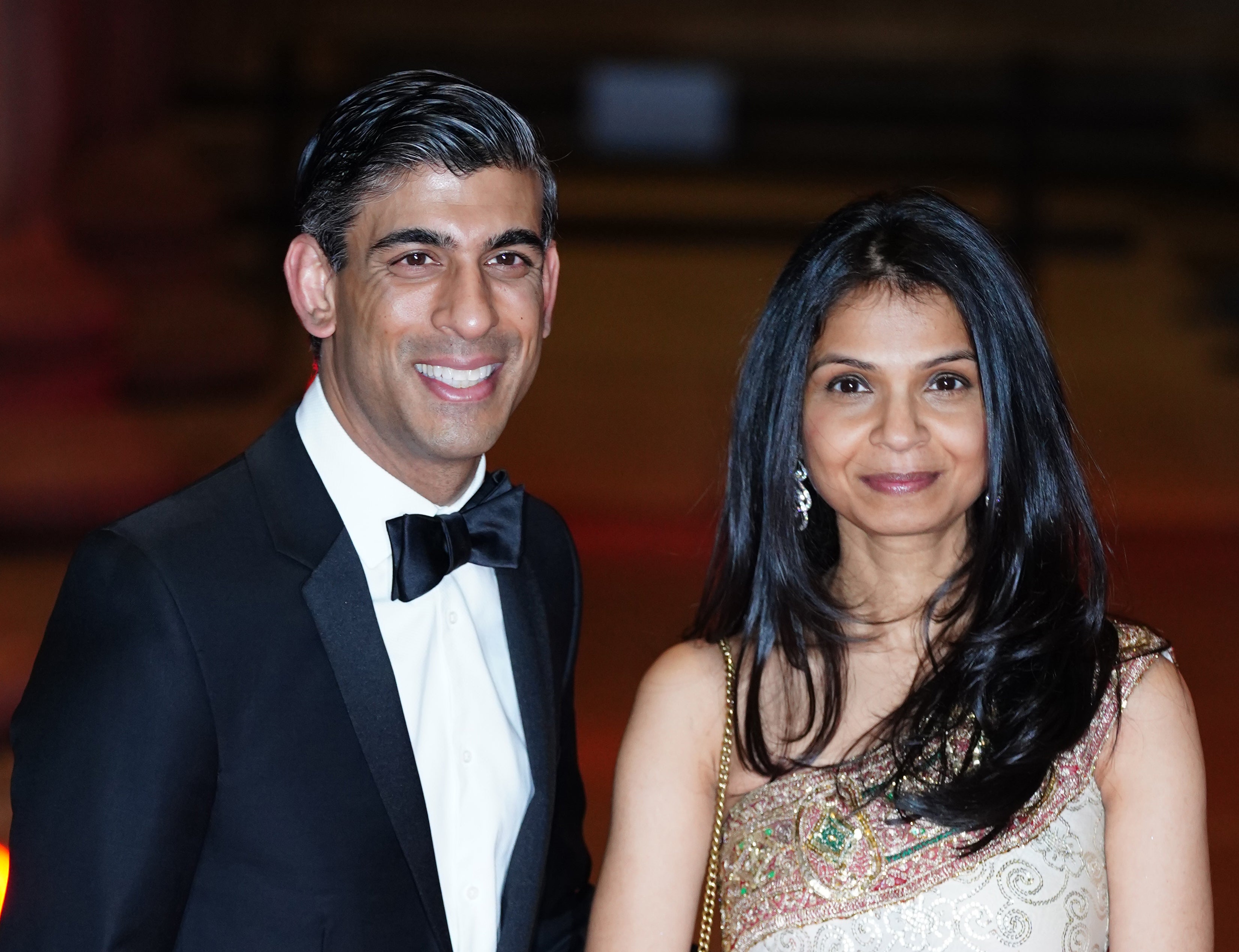

Rishi Sunak’s family wealth highlights the political perils of a successful spouse

Akshata Murthy is discovering the pitfalls of being successful while married to a minister, as Sean O’Grady explains

No chancellor of the exchequer, or indeed member of a British cabinet, has had a spouse quite as wealthy as Akshata Murthy – probably since the Edwardian era, when vastly rich landed aristocrats and industrialists tended to populate the ranks of government.

Rishi Sunak’s wife is worth about £430m and is the daughter of a prominent Indian businessman and billionaire, NR Narayana Murthy. Through her father and via her own activities, Ms Murthy has interests in everything from a gym business and an upmarket tailor (New & Lingwood) to tech giant Infosys. Ms Murthy and her husband have four expensive homes between them. Mr Sunak’s possessions include a £180 hi-tech coffee mug, and yet it would appear he is unused to using a contactless payment card.

Ms Murthy is richer than the Queen, indeed – and there’s nothing wrong with that. But politically it makes things trickier for her ambitious husband, because with great riches come big questions – from Jayne Secker on Sky News, for example, who left the chancellor flustered when she asked him about the family interest in Infosys, a company still operating in Russia despite economic sanctions.

Questions have also been raised about the extent to which Ms Murthy’s businesses benefited from the Treasury’s furlough scheme. Even less fairly, Mr Sunak has been accused of being out of touch with the lives of even the British middle class, let alone those who have to use food banks. His status as a millionaire married to a billionaire makes him an obvious target for media accusations of hypocrisy, and makes ludicrous his attempts to cultivate an ordinary-man-at-the-supermarket image.

The couple’s wealth highlights a more general issue: whereas a minister of the crown is required to put any business interests aside or into a “blind trust”, a spouse or other close family member of a minister is under no such obligation. It leaves them open to allegations of conflicts of interest, real or not. The ministerial code bans even the appearance of a conflict of interest for ministers, but it is silent on declarations of familial business or financial stakes.

It’s nothing new, and there are shades of misogyny in the media fixation with (usually female) spouses who have the temerity to pursue their own careers.

Sarah Vine, an acerbic newspaper columnist and the former wife of Michael Gove, was lazily called “Lady Macbeth”, supposedly driving her hapless husband into seizing the Tory crown: “When you durst do it, then you were a man,” as she never said.

Carrie Johnson is routinely derided as some sort of green seductress, tempting the prime minister to cover the land in wind turbines and recycling centres. Or, worse, responsible for the entire Partygate scandal. This despite the fact that the prime minister is 57, perfectly able to make his own mind up, and known to be sociable by nature; and that the commitment to net zero was enshrined in law by Theresa May.

Samantha Cameron got off relatively lightly for working for a firm of posh stationers and then setting up her own fashion label, while Miriam Gonzalez-Durantez, now Lady Clegg, a lawyer by trade, was only accused of being a secret agent of the European Union by a few unhinged Brexiteers; hubby was plenty Europhile enough.

By contrast, notable male spouses such as Denis Thatcher and Philip May are portrayed as wise senior advisers to their powerful wives, valuable reservoirs of worldly business experience, even though both Margaret Thatcher and Ms May had successful careers of their own before they went into politics.

The most vicious scorn was reserved for Cherie Booth QC. She was accused of wanting to make money – an odd accusation coming from the political right – and of backing the Human Rights Act in order to drum up business for her barristers’ chambers. In fact, the legislation simply enabled cases to be heard in Britain rather than in Strasbourg, and probably made little difference to her considerable income.

Sadly, the “safest” option for the female political spouse (there are few same-sex examples) is either to do absolutely nothing, or to do something like uncontroversial poetry (Mary Wilson) or consensual charity projects (former PR Sarah Brown, and Norma Major).

Anything other than the lowest of low profiles has the potential, fair or otherwise, to damage a ministerial career. Then again, Mr Sunak’s poorly received spring statement, coupled with his vanity, seems to be doing enough harm to his prospects on its own.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks