What are we about to learn from Rachel Reeves about Labour’s economic policy?

As the shadow chancellor prepares to deliver the prestigious Mais lecture, Sean O’Grady looks at what her big ideas could mean for an incoming Labour government – and how likely they are to succeed, especially those that have been tried before...

According to the shadow chancellor, Britain faces a 1979 moment, a decisive shift in economic policy reminiscent of the way in which Margaret Thatcher’s Conservative government broke with the post-war consensus on full employment and a mixed economy – but in a rather different direction, seeing as Rachel Reeves wants to put economic growth at the centre of “a decade of national renewal”.

Delivering the prestigious Mais lecture, more often given by a serving chancellor or governor of the Bank of England, Reeves has been granted a considerable honour – and has given us some insights into her ambitions, should Labour come to power...

What is the Mais lecture?

It’s one of the more important events in the economic calendar, and provides a platform for prominent people in finance and policymaking to set out their ideas at length, enhanced on occasion by some theoretical background and intellectual heft. It’s organised by the Centre for Banking Research, and is named after a former lord mayor of the city of London, industrialist and Labour peer, the late Alan Mais.

Beginning in 1978, it has previously featured distinguished, or at least important, figures such as Mark Carney, Tony Blair, Gordon Brown, Mervyn King, George Osborne and Rishi Sunak. Last year it was the turn of Odile Renaud-Basso, the president of the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development, to tell us all about “How to green the global economy”.

What’s the Big Idea?

Reeves is famously so smart that she can easily hold more than one big idea in her head simultaneously. This is just as well, because she has many big ideas, though, to be fair, some of them – such as the green prosperity plan – are prone to being forgotten about.

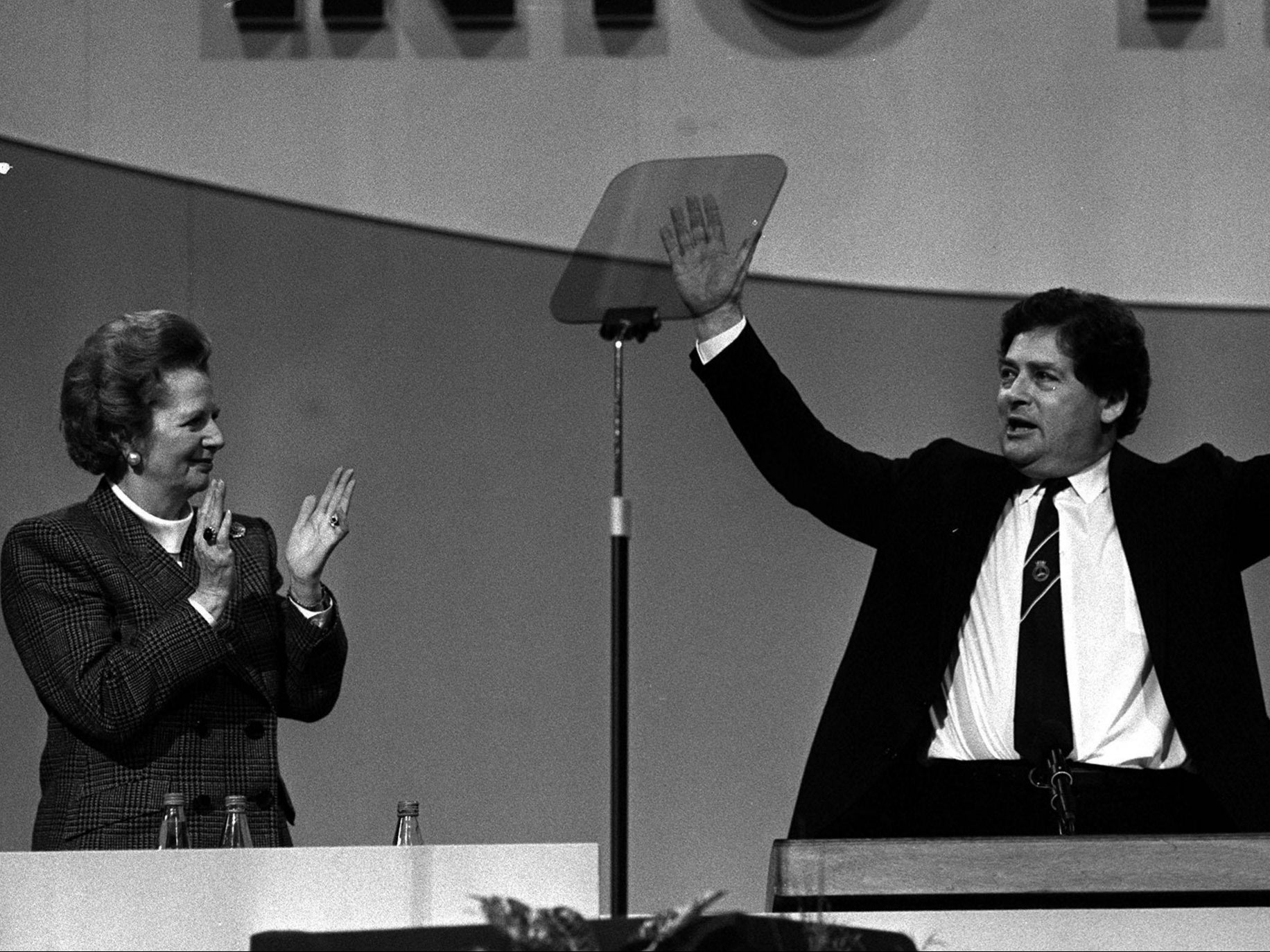

Usually, her iron-clad fiscal rules form the centrepiece of her policy, but this time it’s a take on the supply side of the economy. Reeves takes her cue from the supply-side revolution engineered by Thatcher, Geoffrey Howe and Nigel Lawson in the 1980s – which consisted of smashing the unions, privatisation, liberalising markets, scaling back the welfare state, cutting direct taxation – and, not to be forgotten, establishing the European single market.

In Reeves’s words: “As we did at the end of the 1970s, we stand at an inflection point, and as in earlier decades, the solution lies in wide-ranging supply-side reform to drive investment, remove the blockages constraining our productive capacity, and fashion a new economic settlement, drawing on evolutions in economic thought.”

Isn’t invoking the Thatcher era a bit provocative?

Well, it was an era of mass unemployment, growing inequalities and the end of union power, so it’s a bit bold. Reeves must know that, and therefore it’s probably deliberate from a woman who seems to want to be the most reactionary Labour chancellor since Philip Snowden sought to demonstrate the party’s fitness to manage capitalism in the lead-up to the Great Depression.

Even so, she’s arranged a modest insurance policy to protect herself on her left flank as she attempts to write “a new chapter in Britain’s economic history”: “Unlike the 1980s, growth in the years to come must be broad-based, inclusive, and resilient.”

How will she do this?

This part isn’t entirely convincing. All of the measures Reeves proposes sound pretty much like waffle, and don’t really add up to a convincing plan to raise the rate of gross domestic fixed capital formation. That would entail a set of policies to restrict household consumption in favour of private and public investment, which would imply another hit to living standards (including public services) and to Labour’s chances of re-election.

So instead we have some smaller, less costly ideas that cannot conceivably raise the UK growth rate to be sustainably higher than those of the rest of the G7 group of major industrialised economies – especially not the US. In her lecture, Reeves declares: “Planning reform, strengthening devolution and a new industrial strategy will be at the centre of Labour’s plan for growth. Half a million jobs will created across the UK through a new national wealth fund that will invest in the industries of the future.”

Yet there is no necessary reason why devolution will promote investment, and the “national wealth fund” is capped at £7.3bn, a tiny amount in the context of the national accounts and the task awaiting the new government. Relaxing planning should help build more houses and industrial buildings, but don’t forget that planning rules are there for a reason – the protection of people (and nature) from overdeveloped environments, and to avoid expensive damage to the environment (eg building on flood plains).

Anything else?

Like any other prospective chancellor without much money, Reeves turns to MOG – “machinery of government” – as a partial panacea. She wants to strengthen something called the “Enterprise and Growth Unit”, which was established by New Labour within the Treasury in 1997 – a small body that is “squarely focused on driving economic growth”.

As Reeves says, “It was a source of important policy ideas, including the reform of competition law and the creation of a longer-term science funding framework. So we will build on that success, hard-wiring economic growth into Budget and spending-review processes, with a reformed and strengthened Enterprise and Growth Unit augmenting the existing so-called ‘fiscal triangle’.”

Hasn’t that been tried before?

Yes, and it failed. If the installation of a new government, along with rearranged departments, units, industrial strategies, enterprise zones, and regional/“levelling up” policies, were the key to economic success, the United Kingdom would be the richest place on Earth. From George Brown to Michael Heseltine to Boris Johnson, it’s all been tried, and mostly it has been a waste of time and money.

In the case of Reeves, it doesn’t matter if you “hard-wire” economic growth into Budget and spending-review processes if your iron rules on borrowing and debt take precedence. Hence the death of Ed Miliband’s costly plan to green the economy.

What went wrong with past attempts to prioritise growth?

Institutions got mixed up with policy. It wasn’t the unreformed Treasury, its “bean-counters” and the small-c conservative “Treasury view” that habitually got in the way over the decades. Rather, governments found that their attempts to operate growth-oriented policies were always within some restrictive monetary or fiscal framework, or else sceptical financial markets that in the end stymied the attempt to boost industry and GDP.

The most recent and spectacular example of that was the mini-Budget and the experiment with Trussonomics in 2022, but it applies to most such attempts since the Wilson government attempted a planned economy in the 1960s and was frustrated by the need to maintain the value of the sterling exchange rate (and in the end sadly failed in both objectives).

Reeves – with her iron-clad fiscal rules taking precedence, rightly, as the foundation for a stable economy – has already fashioned a policy straitjacket for herself. Indeed, she has made it even tougher than the one restraining Hunt, by strengthening the role of the Office for Budget Responsibility. In a way, the cancellation of the flagship £28bn green prosperity plan may be regarded as the first U-turn of the Starmer administration.

How could Reeves succeed?

By taxing private consumption heavily, on a scale not seen since the real days of austerity and the post-war Labour government led by Clement Attlee. She may also find that, in an increasingly chaotic and protectionist world, her iron-clad fiscal rules might make the UK a uniquely calm and stable place for investors to stash their money and invest in productive capacity.

Paying down debt would certainly remove one obstacle to growth. So Reeves’s fiscal conservatism will certainly help the country, but it will fail to make the voters feel richer and happier, and workers will be more prone to striking in an effort to maintain living standards. It will be a slow and politically hazardous process.

Otherwise, she’ll just have to hope that AI and other similar exogenous factors will boost productivity, as other technological revolutions – steam, electrification, automation, digitalisation – have in the past. Undoing Brexit, in a second-term Labour government, would also help. In any case, the next few years will be tough, whoever is in No 11.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments