Could the ‘pingdemic’ kill the economic recovery?

Economists are not health experts, and even epidemiologists aren’t sure what to expect, writes Anna Isaac

Where’s the peak?” It’s the most important question for just about everyone in the UK right now, especially those confined to their homes.

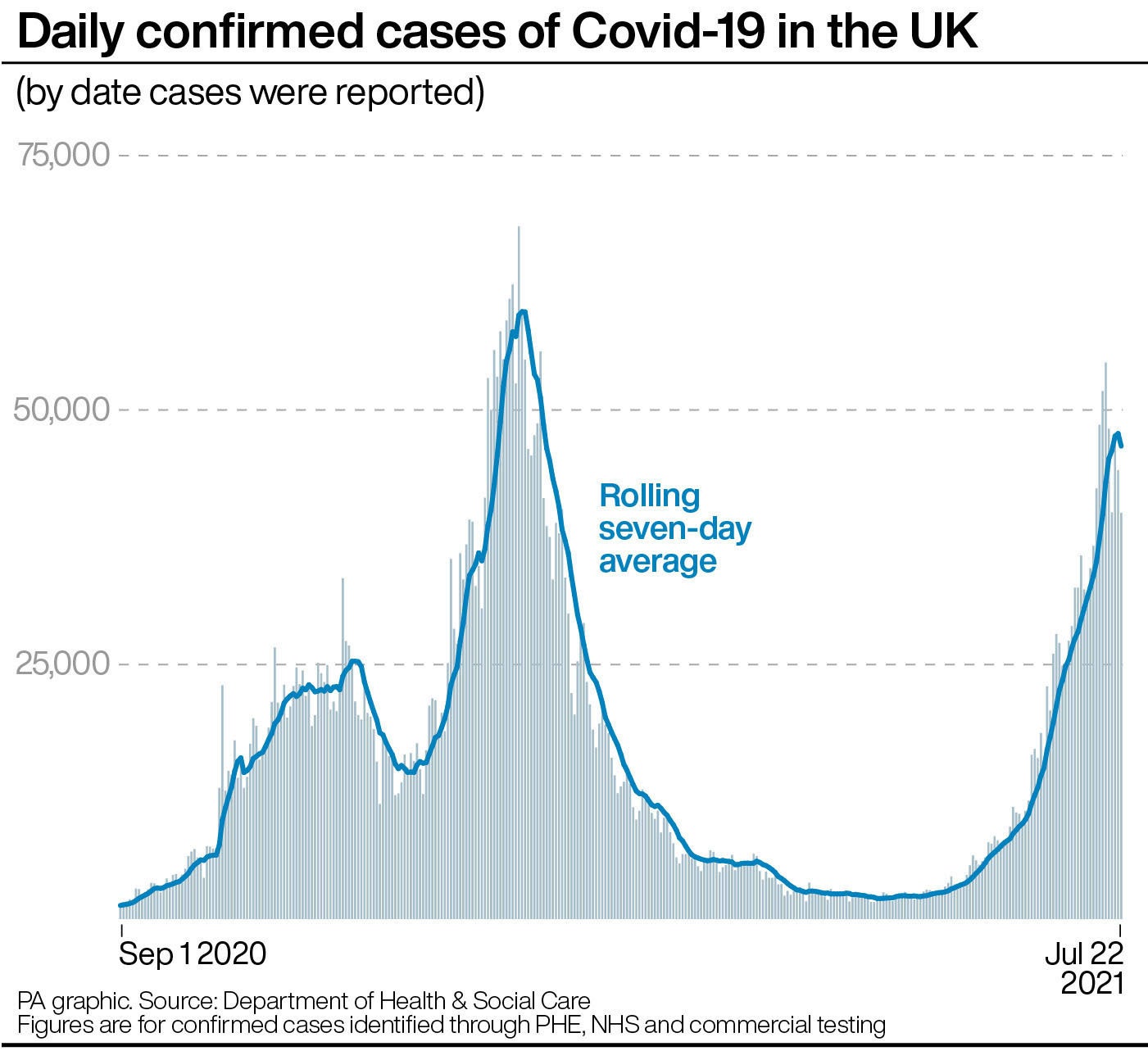

Epidemiologists grappling to work out how high the UK’s infection rate will go aren’t quite sure. Economists, eager to remind everyone that they don’t have health expertise, don’t know either. No 10 seems to hope it’s before mid-August.

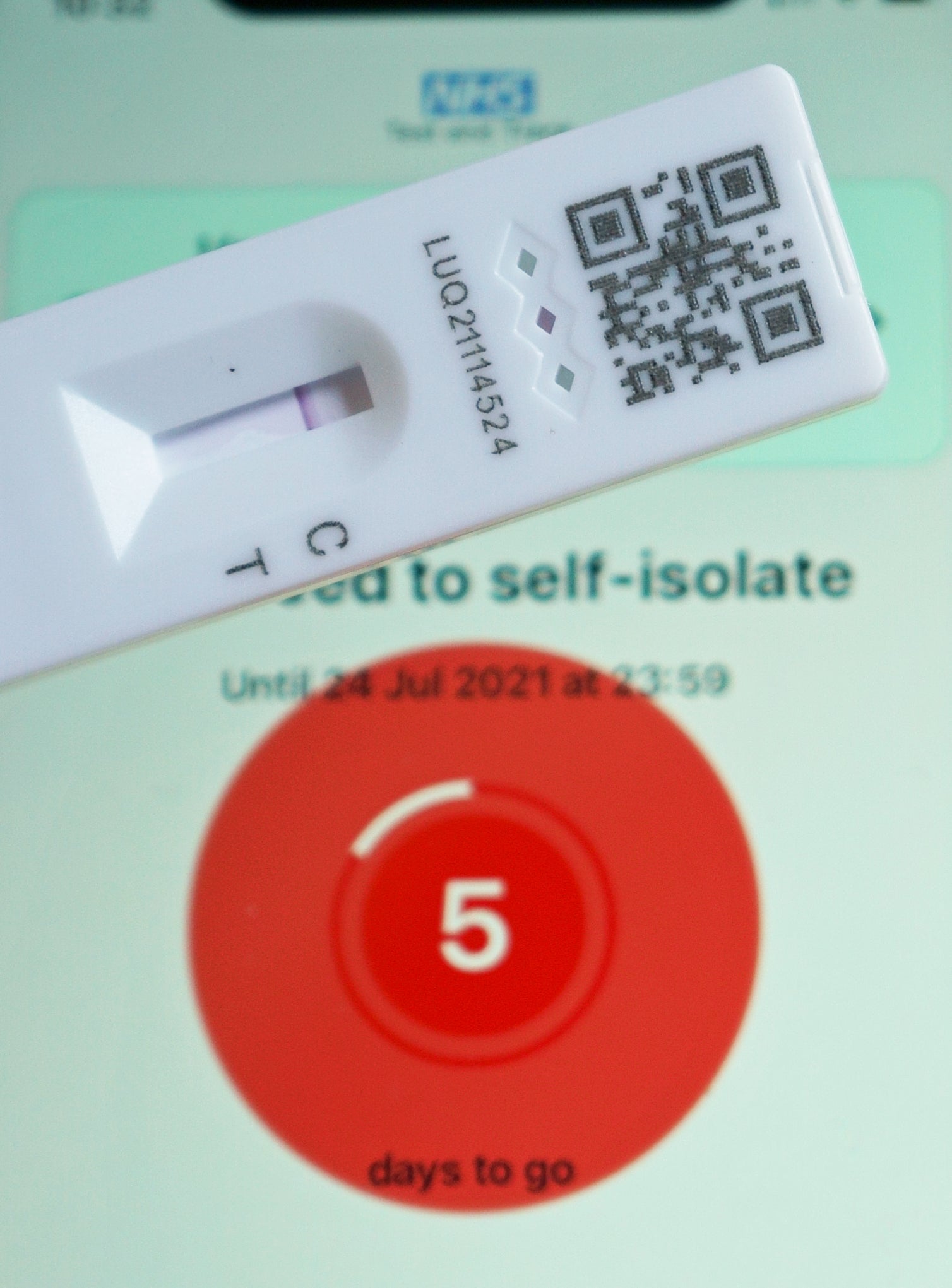

Until then, the impact of both infections is stark, as people are called and asked to isolate by the authorities (a legal obligation) or requested to isolate, “pinged” by the NHS Covid-19 app. It’s not hard to see why: one in 75 people in England, three-quarters of a million, were infected with Covid-19 last week, according to data from the Office for National Statistics. That compares with one in 80 in Scotland, one in 210 in Wales and one in 170 in Northern Ireland.

It’s taking a serious economic toll. New data shows that the “pingdemic” is aggravating existing staff shortages and acting as a handbrake on businesses’ growth.

There’s a hint from No 10, that the peak might come around mid-August in their modelling. That’s because from 16 August people who are otherwise fully vaccinated (two weeks after a second jab in most instances) will no longer have to isolate if they come into contact with an infected person.

At a practical level, until mid-August, “the sheer number of people [having to isolate] is going to keep getting higher,” says Andrew Goodwin, chief UK economist at Oxford Economics. “A lot of close contacts are in the workplace.” That means whole shifts of workers can be taken out of action at once, and while the government has broadened its list of industries who can use testing to avoid isolation, it’s still a short one.

The shape of this wave also won’t be like others this time, unless there’s a policy U-turn on the “irreversible” approach the prime minister has previously described.

Previously, after a Covid-19 infection wave hit, the response was a lockdown which rapidly brought down infections. This time, riding out the wave will mean higher rates of infection for longer. It’s very hard to know when this peak will land, something that’s crucial when it comes to the pace and timing of the economic recovery.

If most working age people are fully vaccinated, and they will no longer have to isolate after mid-August, the economic impact of the pingdemic should be limited and temporary. Schools should also operate more effectively if postive-testing individuals are sent home, over groups of those exposed.

“It does require people to actually be responsible and test themselves,” Goodwin says.

It’s not all just about pings, either. The shape of furlough has a part to play in staff shortages. Those on furlough are most likely to come from industries that saw high levels of job losses in previous lockdowns, but which also have high numbers of vacancies now, such as hospitality. There will be more flexibility in the labour market after furlough ends as people shift into new jobs within their industries.

There are two other big unknowns, too. One is how bad a flu season the UK will have and another is the risk of a Covid-19 variant that can escape vaccines. Dr Jenny Harries, chief executive of the UK Health Security Agency, said in a blog published on Friday that a likely worse than normal flu season “combined with the likelihood of continuing circulation of Covid-19, means this coming winter will again be highly unpredictable”.

Economists agree that the months ahead are full of unknowns, and many will be watching the bellwether of another lockdown, hospitalisations, like hawks.

“The outlook is fraught with uncertainty,” says Kallum Pickering, senior economist at Berenberg Bank.

But beyond what could prove a bumpy ride this winter, other economic factors, often termed “underlying” measures of economic health, are in decent shape. Banks are well capitalised, and household balance sheets appear robust, he says. A tough few months of combined Covid-19 infections and flu would probably delay, not derail, the economic recovery in his view. Compared to economists’ predictions earlier this year, the UK economy has held up much better than hoped this year.

“If we lost some momentum going into the autumn and winter, I’d just add that to my outlook for next year,” Pickering says.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments