Why Boris Johnson’s failings in the north will come back to haunt him

The successes of the devolved administrations during the pandemic have exposed the mistakes in Westminster, writes Sean O’Grady. The row over the new tiered lockdown system provides a great opportunity for mayors to demand more powers

Not so long ago, the United Kingdom was one of the most centralised of the mature democracies, with only France having more power concentrated at the centre. Now, however, thanks to successive waves of devolution to Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland, and the establishment of powerful elected mayors across many of its major cities, the task of governing Britain is becoming an increasingly complex and transactional one. An unlikely alliance of Brexit and Covid-19 is exacerbating and exaggerating differences in a way that would have been impossible before Tony Blair’s government began this process of far-reaching constitutional reform almost a quarter century ago – one that was given added impetus under David Cameron’s administration, with its grand talk of the “northern powerhouse” and granting local government more freedom to spend money as it thinks fit. To the casual observer, or at least an unkind one, it looks like the Balkanisation of Britain.

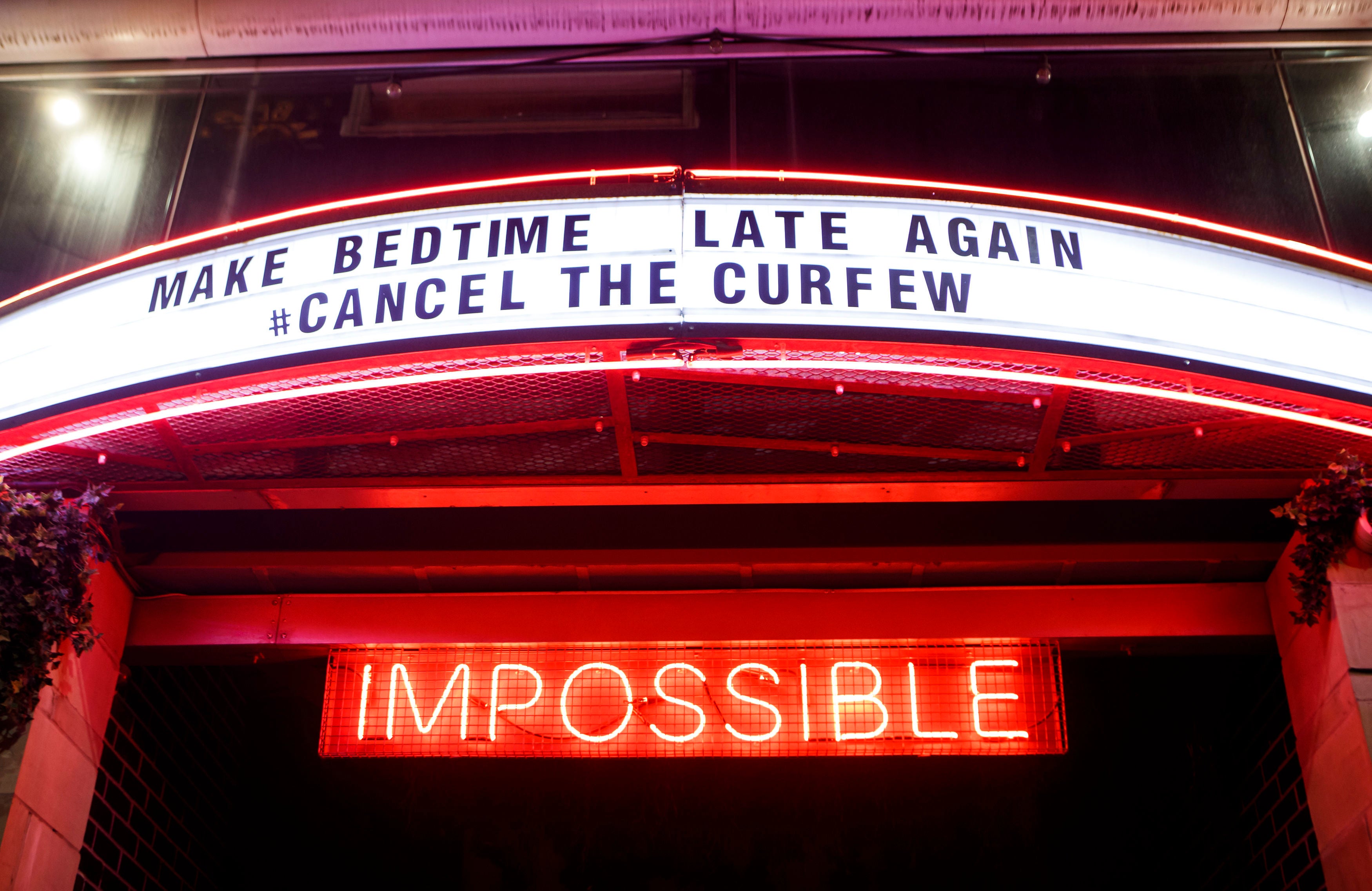

Even a government with a working majority of 87, in the middle of a public health pandemic, is unable to easily impose its will on, say, Middlesbrough, Manchester or Liverpool. Northern mayors, with Andy Burnham in Manchester proving the most powerful voice in the bully pulpit, have used the authority of their popular mandates to question government policy. They ask, rightly, for the scientific basis of the government’s new measures. The mayors, equally understandably, also demand financial support commensurate with the economic sacrifices their conurbations and regions are being asked to make. Above all, they have complained loudly about not being consulted about what is being done to their cities, and hearing the news from the newspapers. With far fewer formal powers than Nicola Sturgeon in Scotland, Mark Drakeford in Wales and Arlene Foster in Northern Ireland, the likes of Burnham, Joe Anderson and Dan Jarvis are punching above their weight in Manchester, Liverpool and Sheffield respectively. Sturgeon, meanwhile, has made the most of differences between Edinburgh and London on Brexit as well as public health. She looks forward to a landslide of her own in next year’s Scottish parliament elections, and a renewed bid for independence. Even with Covid-19, Scotland wants to develop its own “tiering” framework, just as it has gone its own way on the app, mandatory face coverings, and other measures. Critics say the SNP tweaks UK arrangements for the sake of it, to the detriment of a clear UK-wide public message.

That they have been able to do so is also a factor of the weakness of central government’s response to Covid, most glaringly with the failure of test and trace. As Boris Johnson’s ratings have slumped, so has his ability to ignore local objections. That the north of England has found its voice is also an unexpected consequence of the Conservatives’ newfound interest in the fortunes of people living north of a line from the Bristol Channel to The Wash. George Osborne, MP for a Cheshire seat until 2017, started the revival, while Brexit and Johnson’s vague agenda of “levelling up” pushed it still further. The Tory capture of once-safe “red wall” seats in the north and Midlands in successive general elections since 2010 has turned the north into a powerful and vocal interest group within the Conservative Party. Perhaps sensing danger, a group of 35 of these MPs recently formed the Northern Research Group (NRG), to better pursue their interests. Whether the new chair of the NRG, Jake Berry, Tory MP for Rossendale and Darren since 2010, has the energy to take on his colleagues in government remains to be seen. While he has little in common politically with Burnham, say, they share an interest in making sure the northwest gets as much attention as Scotland or Sadiq Khan’s London. They, like the devolved administrations, tend to barter political cooperation with Whitehall for public investment, tax breaks and other pecuniary concessions. It is not ignoble, necessarily, or anything like a novelty – democracies have always been prone to “pork barrel” politics. On this scale, however, it is new to Britain, where “regional policy” was, ironically, traditionally directed from London.

What seems to be emerging in sharp focus in the Covid crisis is a rather untidy, asymmetrical and often inconsistent system of devolution. Fiscal powers vary radically from place to place and there is no real “clearing house” where regional and national interests can be reconciled, as America does via the Senate, for example, or Australia and Germany do with a much more consistent pattern of responsibilities at state level. The modest arrangements for four-nation coordination are pointedly ignored in Downing Street. The repatriation of functions from the EU, and the UK Internal Market Bill, have simply caused more bad feeling. Only Spain, once also a highly centralised country, has the mind of differential devolution that the UK does, and equally unhappily.

The “West Lothian” question was about why Scottish MPs may vote on English laws at Westminster, but English MPs have no vote in Scottish bills before the parliament in Edinburgh. It now seems to be the case that popular mayors of big cities, such as Khan and Burnham, have more clout than smaller places which have persevered with the old system of council leaders, such as most of the southern shire counties.

There is, then, much more scope for political division as this territorial politics becomes more established, though there remains no great appetite for devolution to the English regions, which enjoy weak popular affection. What is increasingly striking is that the only part of the UK without devolution or a voice of its own is England, representing some 84 per cent of the UK population. So far, no one, with the possible exception of Nigel Farage, seems inclined to “speak for England”, but as Covid and Brexit add to the tensions within England as well as between England and Scotland, that doesn’t seem likely to change.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments