Could the Liberal Democrats be on the brink of an electoral breakthrough?

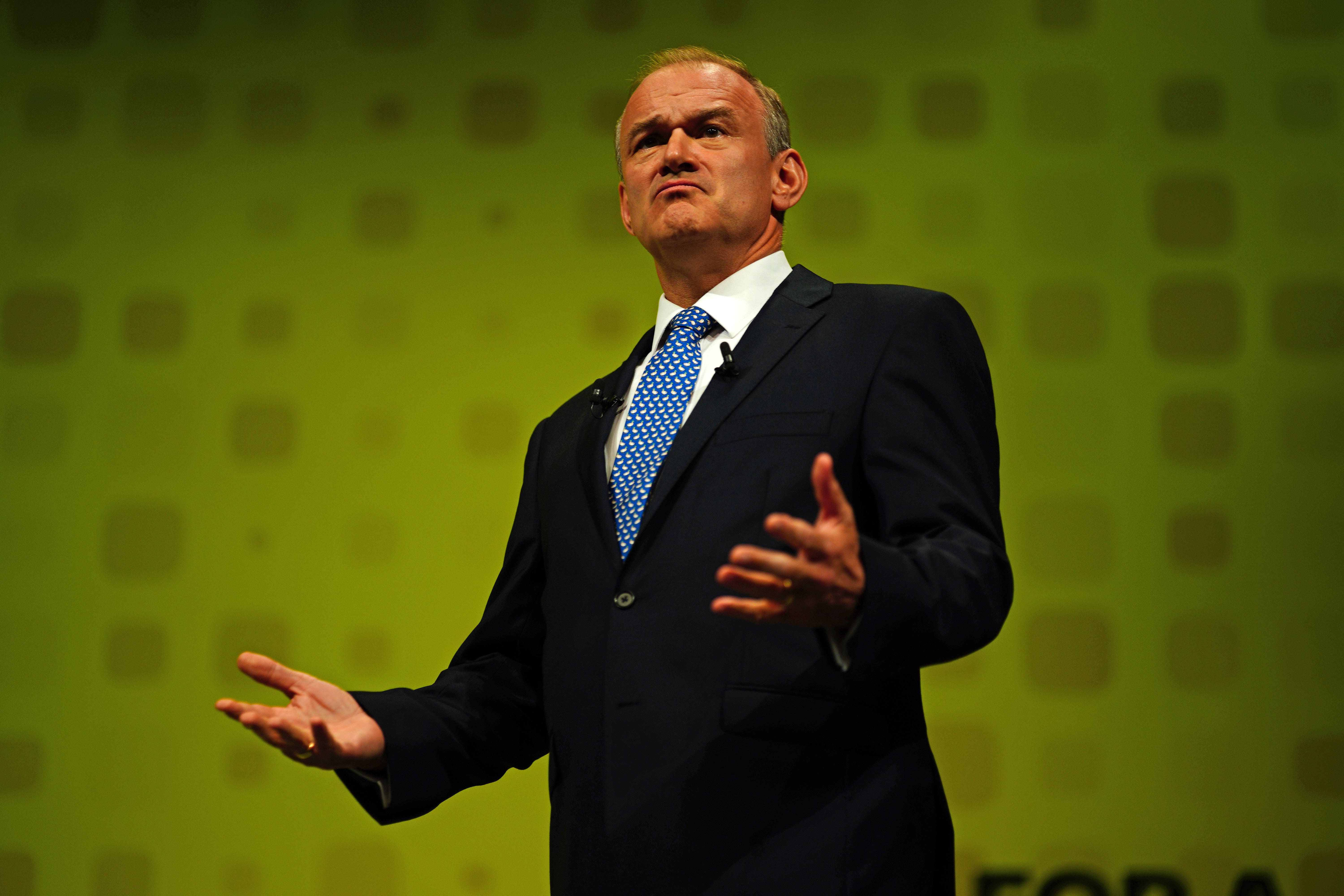

Ed Davey claims this year’s election will be a ‘once in a generation’ event but giant egg-timers and cheesy slogans aside, what are the prospects for the Lib Dems? Sean O’Grady takes a realistic look at their chances of becoming a parliamentary force to be reckoned with

The Liberal Democrats have had their spring conference and have launched their local election campaign with a typically cheesy photo-op featuring Ed Davey, a giant cardboard egg-timer, and the slogan “Time’s Running Out Rishi!”.

For the first time since the brief outburst of “Cleggmania” during the 2010 campaign, the party has realistic hopes of winning a substantial number of parliamentary seats at a general election, even though it is still languishing in the polls. Davey claims it will be a “once-in-a-generation election”.

On the other hand, a likely Labour landslide means the Lib Dems may have comparatively little influence in the new House of Commons. There remain significant challenges for Davey and his loyal followers...

What do the Liberal Democrats stand for these days?

A close analysis of the speech Davey gave to the spring conference reveals that they’re more ambitious than Labour on green energy (though less than the Greens) and on public services. Less radically, they advocate “an immediate bilateral ceasefire in Gaza”, indicating a position practically identical to that of the other national parties. They also want to get all three parties together to sort out social care.

In the words of Davey: “We can elect many more brilliant Liberal Democrat MPs to fight and win the case for bold political reform. The real change we need to transform our country for good – to fix the health crisis, the cost of living crisis, the sewage crisis – and give people the fair deal they deserve.”

Notably absent is any talk about reversing Brexit, and Davey confines himself to “fixing our broken relationship with Europe” without offering specifics. It is a shame because one of the great constants of post-war politics has been the party’s commitment to what became the European Union. This, for instance, is from their 1955 manifesto: “The Liberal Party has been, and will continue to be, critical of the timidity and hesitation which both Labour and Conservative governments have shown about associating this country intimately with the movement to secure some measure of European unification.”

They no longer use such language, but given the increasing unpopularity of Brexit among their target voters, they might be tempted to be a bit more enthusiastic about the EU.

Will they win the local elections?

No, but they should come second – they can capitalise on their traditional strength in the municipalities to make some substantial gains and command a respectable share of the vote. The contests on 6 May should prove to be an encouraging launchpad for the general election push and may confirm that the Conservatives are still, even now, on a downward trajectory.

This rebuilding of the local activist/councillor network is helping to pave the way for a bumper harvest at the general election and is re-establishing the party as a national force. As the Starmer government takes more unpopular decisions, and the Tories descend into civil war, the Lib Dems (and Reform) could make further gains in by-elections and in local councils. British politics would enter a more fluid, dynamic phase.

How’s the general election looking?

Surprisingly good, in terms of prospective gains in the number of Liberal Democrat MPs even on a fairly measly share of the vote. If you believe the polls, Davey could score about the same share of the vote as, or even less than, his predecessor Jo Swinson did in 2019 (11.7 per cent). Although she presented herself as a viable candidate to be PM on a pledge to stop Brexit, that performance was one of the weakest in a general election since 1970.

The difference in 2024 is that Brexit is no longer an issue (rightly or wrongly), the mood to “get the Tories out” is far more intense, and the willingness of Labour and other voters to “lend” their votes to the Liberal Democrats tactically is at its highest level since 2001. The Lib Dems have also, long ago, learnt the art of targeting their efforts.

The party could benefit greatly from the collapse in the Conservative vote, especially in the blue wall in the South. The decline in Tory fortunes from their high point in 2019 is of such proportions that opportunities are opening up. The by-election wins in Tiverton and Chesham, for example, and encouraging local elections – all with solid evidence of tactical voting – also augur well.

So the Lib Dems can make a lot with a little, and the conditions for success are good. They can reasonably expect more than 40 seats next time round – but their total might conceivably exceed the 52 seats won by Charles Kennedy in 2005.

It’s worth mentioning, too, that if they were nearer to 20 per cent of the vote than 10 per cent, they might even push the Tories into third place in the Commons and become the official opposition. Well, they can dream.

By comparison, Reform UK might well gain more votes nationally than the Lib Dems but win few, if any, parliamentary seats because their vote is relatively evenly spread across constituencies; there are only a few places where they could effectively challenge one of the major parties. They also lack much of a local machine on the ground.

This unfairness will no doubt be a talking point after the election and is made all the more poignant for Reform because it is their intervention that will reduce the Tory vote so much that the Lib Dems can take these now more marginal seats. Under proportional representation, the Lib Dems and Reform would win about 60 seats each in the Commons.

Where are their best prospects?

Broadly in the South West and the home counties. Many of the seats they won and held during previous Liberal revivals and then lost in the 2015 election disaster seem set to be regained – Yeovil, Winchester, North Devon, Newbury and Ely, among other past glories.

They also hope to make further inroads in the comfortable South, in seats in Surrey and Cambridgeshire, for example, with the prospect of ousting cabinet ministers such as Lucy Frazer, Jeremy Hunt and Michael Gove. But they seem unlikely to win back many old bridgeheads in Scotland, Wales, or the north of England.

And what will that new third force in parliament mean?

The Liberal Democrats will once again be the third-largest party in the Commons, supplanting the SNP, and Davey will have a regular slot at Prime Minister’s Questions. They’ll also gain the opportunity to chair some select committees and generally enjoy a louder voice.

Depending on the scale of the Labour landslide and the extent of dissent among Labour backbenchers, the Lib Dems might find themselves in a position of strength and power on some Commons votes. But on the whole, they won’t be able to change much – even less than Paddy Ashdown did with Tony Blair when the two parties concluded an agreement on constitutional reform and a joint cabinet committee for a couple of years after the 1997 election.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments