Is there real reason to fear a Labour ‘supermajority’?

As election day approaches and the Tories look set for a defeat of historic proportions, Sean O’Grady busts some myths about what Labour might do in the event of a landslide

Wisely or not, the Conservatives have tacitly conceded not just defeat but an appalling humiliation on polling day, and are now begging for mercy. Somewhat unconvincingly.

The prime minister himself, in the dying days of his administration, has declared: “I don’t want Britain to sleepwalk into the danger of what an unchecked Labour government with a supermajority would mean.”

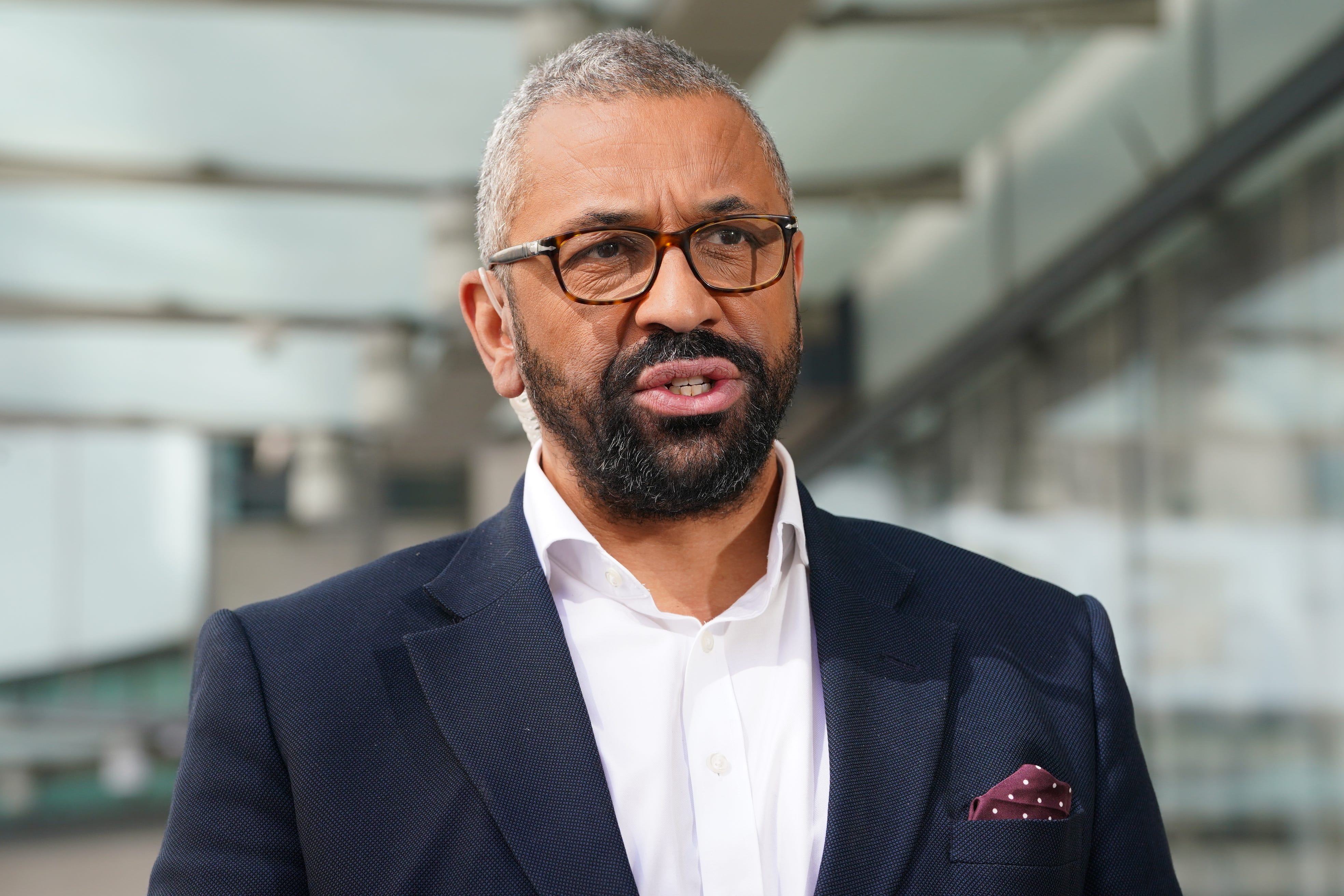

The home secretary, James Cleverly, agrees and says that Labour would “distort” the constitution: “I think there’s a real risk that they take a majority, if that’s what they get, to try to lock in their power permanently, because they don’t really feel confident they’re going to be able to make a credible case to the British people at the next election.”

Not all such fears are fully justified.

What is a supermajority and what would it mean?

The concept of a “supermajority” in the usual constitutional sense doesn’t exist in the British system. It does in other countries, where, typically, a two-thirds majority in a parliament is required to enact major constitutional change. There was one such provision in the UK, under the 2011 Fixed-term Parliaments Act, to authorise an early election, but that was abolished a couple of years ago.

What Rishi Sunak, Grant Shapps and others really mean is just “beyond a landslide”, because there is no word for the scale of the unprecedented majority Labour is about to win – perhaps 250 seats over all other parties and a staggering 350 over the Conservatives. Historic.

But won’t Labour be able to do what they want?

No more than any other government, because a majority of one (or in some cases even a tie) is all that is needed for the House of Commons to pass or abolish legislation, or to vote a government out of office. In practice, governments with very large majorities can have more trouble with discipline, because rebels know that the government won’t fall. Besides, sometimes opposition parties will support the government. Hung parliaments can, paradoxically, strengthen party loyalties.

Will they be entrenched for generations?

No. We can vote them out next time, probably in 2028 or 2029.

Surely Starmer will be unchecked?

No more or less than Asquith, Attlee, Macmillan, Wilson, Thatcher, Blair or Johnson, who also enjoyed very large majorities. We still have the Lords, the courts, the free press, Commons committees, independent bodies such as the Office for Budget Responsibility, the monarchy (in extremis), Labour rebels, and, of course, the opposition parties to restrain excesses. We’re not an elected dictatorship yet.

What about the Lords?

Cleverly claims that Labour will, in effect, rig the Lords – but Labour’s policy, as published, is rather more modest, and appears sensible. The very last of the hereditary peers will lose their right to vote – but there are only 91 of them out of about 780 in total (and some could be appointed life peers, instead, and carry on).

Labour also wants to bring in a compulsory retirement age of 80, and it’s not clear whether that would amount to any great partisan advantage. Because these proposals are in the manifesto, they can’t really be blocked by the Lords under the Salisbury Convention; but anything more radical would meet with stronger resistance, and arguably be unconstitutional, subject to a view from the Supreme Court. Labour doesn’t look keen to spend time on this, though “immediate modernisation” is promised.

Votes for kids?

Extending the franchise to 16- and 17-year-olds is a policy that has been adopted by Labour, the Liberal Democrats, the Green Party, the SNP and Plaid. It will undoubtedly happen and will make some difference, both electorally and in terms of making politicians listen to what young people want, for example, from higher and further education.

At the moment, support for the Conservatives and Reform is extremely low among the very young – but there are no iron laws in politics. In Europe, the teenagers are much more right-wing, while there was once a time when Labour could rely on the pensioner vote. Nothing is immutable.

Will Labour give prisoners the vote?

There’s no evidence for this, though the Tories claim it is the case. There is an old, outstanding judgment from the European Court of Human Rights requiring such a measure, which has long been ignored by governments of both parties. The Tories could claim that Keir Starmer, a human rights lawyer, is more likely to implement it, but he won’t.

Foreign nationals?

Some already have the vote, eg Irish and Commonwealth citizens. Starmer used to say he’d grant the vote to EU nationals resident in the UK, but has since dropped the idea.

Did the Tories mess about with the franchise?

But of course. They changed the voting system for the regional mayoralties to help their candidates (albeit to no avail); allowed all expats (disproportionately Tory) to vote for a UK MP no matter how long they had lived abroad; and introduced photo ID, which tends to help the Tories a bit.

Labour, by the way, doesn’t wish to reverse these reforms, only wanting to “improve voter registration and address the inconsistencies in voter ID rules that prevent legitimate voters from voting”. Reportedly, automatic enrolment on electoral registers to help with engagement is something Labour may do.

Are we going about this the right way?

No. The Electoral Commission, whose independence was eroded by the Tories, should make proposals that command wide cross-party, cross-community support on such matters. Gerrymandering is wrong, no matter who does it.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments