Why Britain needs a post-Brexit trade deal with India

Modi’s stance on Ukraine and attacks on the BBC mean leaders have plenty to talk about, says Sean O’Grady

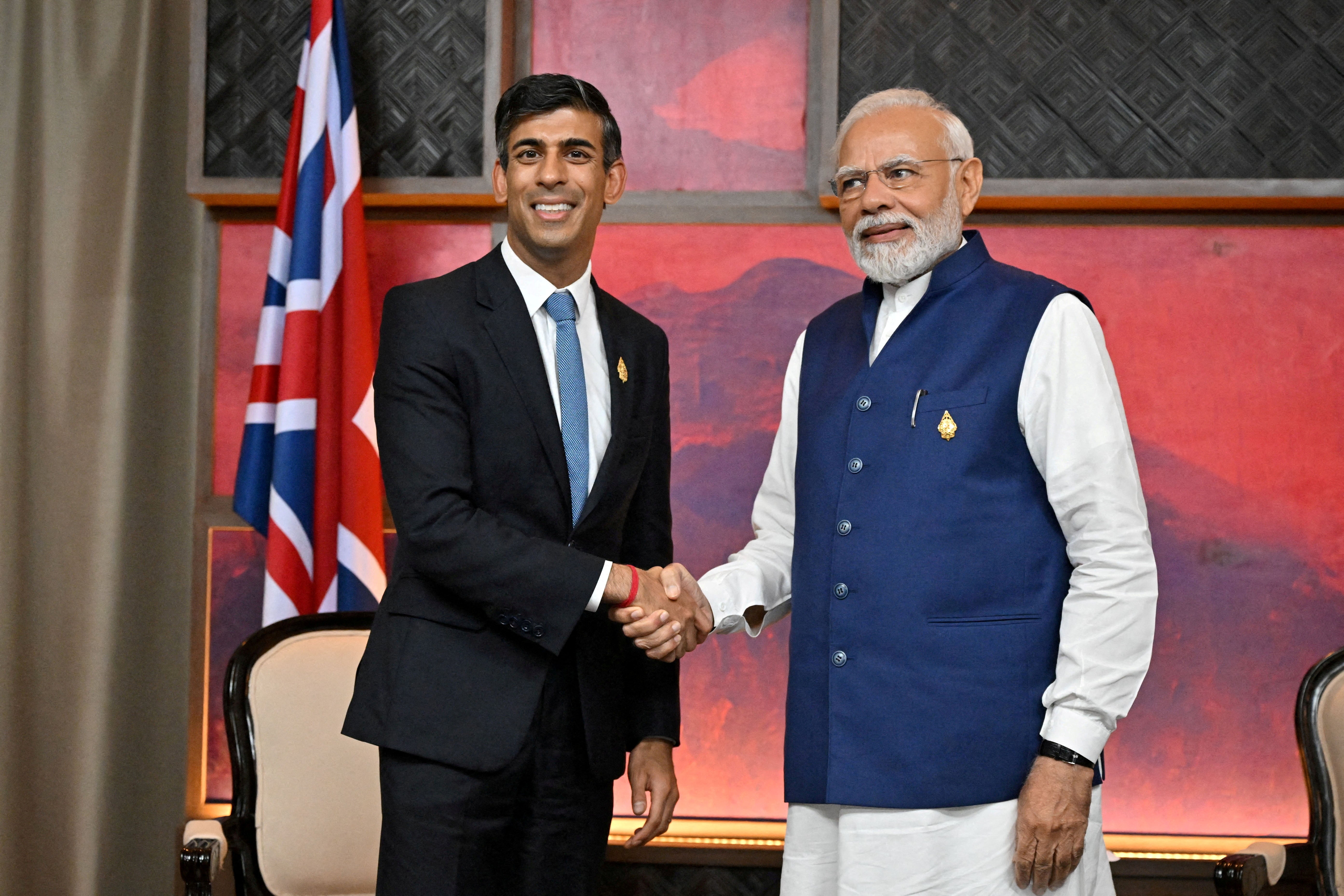

Rishi Sunak has held telephone talks with Indian counterpart Narendra Modi, focused on the slow-moving free trade agreement between the two countries about which there is much goodwill. However, the relationship has been complicated by a range of issues including a row over the BBC and some historic resentments brought to the fore by the upcoming coronation of King Charles. The leaders will meet face-to-face at the G7 in Japan next month, as well as at the G20 in India later this year.

What was the purpose of the phone conversation?

In short, a trade deal. UK-India bilateral trade was worth £34bn in 2022 – growing by £10bn year-on-year – and the emerging economic superpower is post-Brexit Britain’s best bet for hitching itself to a sizeable economy. Long-term benefits of a free trade agreement with India would probably dwarf those from the recent Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership, also known as the Indo-Pacific trade bloc. With the chances of free trade deals with America and China remote at best, an Indian tie-up would be a tangible Brexit benefit for Mr Sunak, a long-standing and sincere Brexiteer.

According to the official readout of the talks, the pair “reflected on the huge opportunities a deal would offer to Indian and British businesses and consumers” – and well they might. Both countries need to pick up the pace of sustainable growth, and open a new chapter in a chequered history going back centuries.

British diplomats also hope to enlist Indian support against China’s expansionist agenda, more active help for Ukraine, and an end to Modi’s recent persecution of the BBC in India for simply doing its job. Ideally for the UK, India would join Japan and South Korea in the US-led resistance to Chinese territorial ambitions in the region; but India is keeping its options open and placing its own interest first.

What’s the problem with free trade?

India has traditionally shown resistance to foreign entrants in sectors such as services and retail, and in general its “permit raj” ethos makes business and trade cumbersome, especially for the unfamiliar.

But those are not the most formidable obstacles; were it not for the tricky issue of UK visas for Indian students and post-graduates entering the British labour market, a free trade agreement would have been concluded years ago. However, as home secretary and later as prime minister, Theresa May refused to countenance a more generous allocation of study or work permits for Indians and Tory hostility to any migration has persisted, not least from present home secretary, Suella Braverman.

Don’t Britain and India see the world the same way?

Both are democracies, both are Commonwealth members, and to some extent they share a common language, enjoy cricket, curry and tea, but India has long had a different worldview to Britain. For many years after independence in 1947, India was a leading member of the non-aligned movement, though notably friendlier to Russia than America (which tended to ally with rival Pakistan) or China (where border disputes around the Himalayas and jostling for regional influence soured relations for a long time).

Now, India is gravitating towards a loose bloc also comprising China, Russia, South Africa and Brazil, and has used its present chairmanship of the G20 to build up that nexus. It means India’s attitude to the war in Ukraine has unhelpfully (for Britain) veered from neutrality to effectively helping Russia beat Western sanctions by buying its oil.

Is this a relationship of equals?

As India’s economy flourishes while Britain’s stagnates, the relationship is increasingly unbalanced. Many of Britain’s most important industries depend on Indian investment, including steel, and celebrated brands such as Jaguar Land Rover and Tetley tea. The potential for more trade in capital, products, services, and skills is immense.

However, the realities of trade are based on the balance of economic power, and this has tilted strongly towards India since her governments abandoned decades of Indian-flavoured protectionist socialism and more or less embraced globalisation. Taking into account the vagaries of exchange rates and data collection, the Indian economy ranks about number 4 in the world and is two to three times larger than the UK economy which sits in tenth place, nip and tuck with France. UK per capita income is higher, given the huge difference in populations, but the sheer heft of Indian output and the size of the market counts for a lot in trade talks, and geopolitics.

What lies ahead?

Fiercely nationalistic Modi won’t be attending the coronation (unlike in 1953 when Nehru came) and India’s president will attend instead. Buckingham Palace has decided to leave the crown featuring the Indian Koh-i-Noor diamond back at the Tower of London rather than have it modelled by Queen Camilla, so as to avoid stirring up tensions over imperial plunder. India would like its diamond back, and it doesn’t seem to be much use to Britain beyond its appeal as a rarely-glimpsed reminder of an imperial past long since faded. It is more than a century now since a British monarch followed the coronation at Westminster Abbey with an equivalent grand Durbar in Delhi, where Indian princes could pay homage to the king-emperor – an almost unimaginable state of affairs seen at this distance. Maybe the British could cut a deal on the famous diamond now?

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments