Has David Cameron stolen a march on Keir Starmer with a progressive Palestine policy?

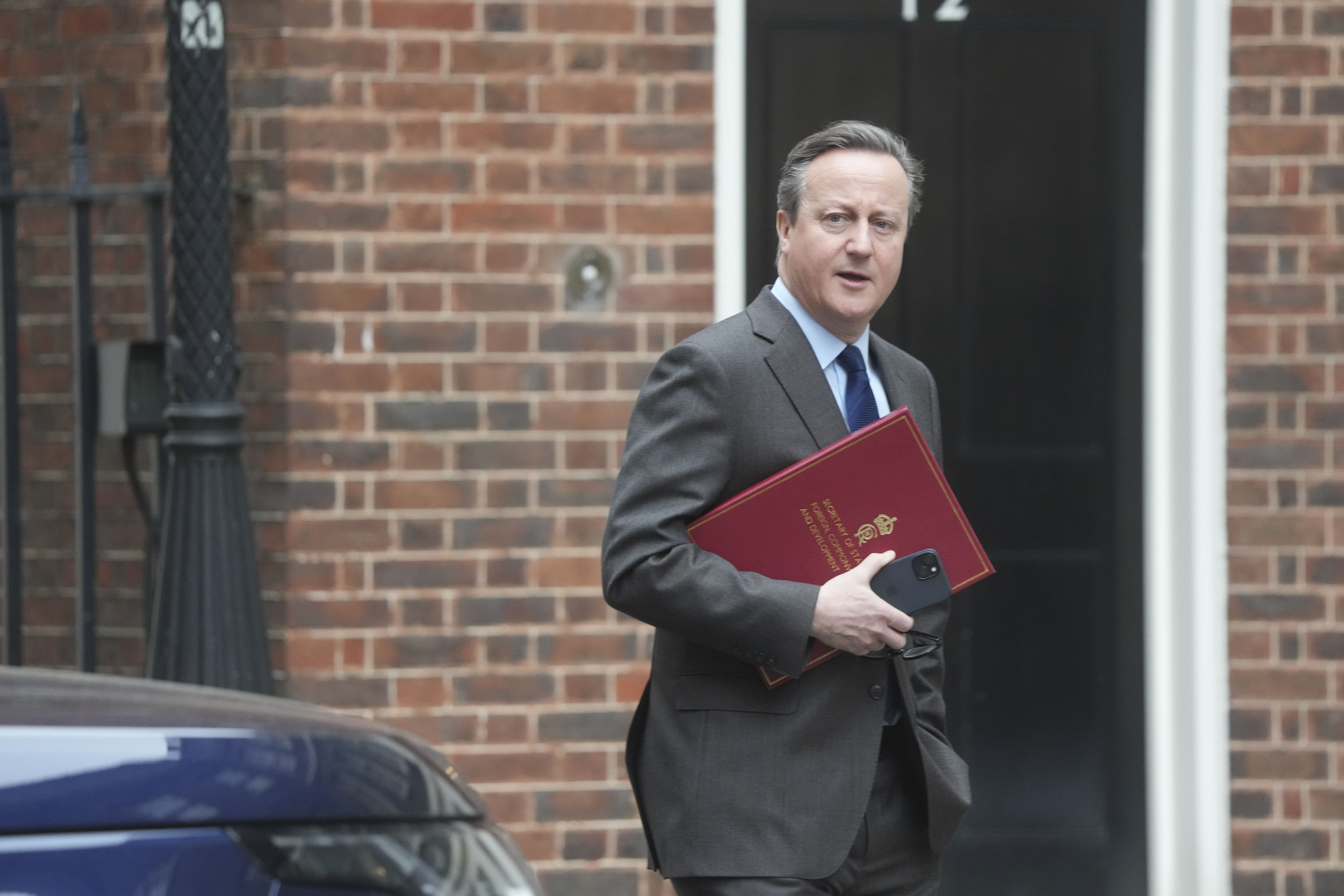

If the British public were surprised to see David Cameron in frontline politics again, no doubt they will be shocked by the former PM pushing a nation state solution for Palestine that sees him outflanking the Labour Party. Sean O’Grady explains what we are witnessing

Lord Cameron was a controversial as well as surprising appointment as foreign secretary last November. The fact that he’s not directly accountable to the elected House of Commons triggered legitimate complaints, while the Tory right resented someone they thought a dangerous Remainer centrist being brought into government (notwithstanding the fact that it was he who granted them their in/out EU referendum).

In any case, Cameron, as a former prime minister, seemed to have been put in to amplify post-Brexit Britain’s voice in the world, and he has quietly set about that task by starting some radical initiatives. He’s taken a bold message on Ukraine directly to the US Congress, for example. In a remarkable departure, the old smoothie has declared in their journal, The Hill: “I am going to drop all diplomatic niceties. I urge Congress to pass it [an aid to Ukraine bill]…I do not want us to show the weakness displayed against Hitler in the 1930s.” But his emerging diplomacy in the Middle East is more portentous still...

What has Cameron been saying?

Three things of particular note. First, he has subtly modulated the standing policy of demanding a temporary humanitarian pause in the fighting in Gaza and a later, uncertain “sustainable” ceasefire into one where the pause can evolve into a lasting ceasefire. In his words: “A pause would be great for hostages, good for aid and we might be able to turn that into the sustainable ceasefire that we want without a return to fighting.”

Second, in another departure, Cameron has announced sanctions on individuals involved in serious human rights abuses in the West Bank: “The UK is clear: we will hold to account those who undermine prospects for peace.”

Most momentously, though, is Cameron’s increasingly insistent advocacy of the recognition of Palestine as a full nation state before any overarching peace deal – as a way of actually making such a deal happen rather than an incentive for Israel to avoid such an agreement. In its way it is a break with the cross-party mantra of “the two-state solution”, partly prompted by the fact that Benjamin Netanyahu has rejected it out of hand. Cameron has said: “We should be starting to set out what a Palestinian state would look like – what it would comprise, how it would work.”

Does what Britain says matter?

Yes and no. “No” because the UK has long since ceased to be a global power and, especially outside the EU, lacks the kind of diplomatic heft possessed by the Americans and major regional powers – Israel, Iran, Egypt, Saudi Arabia and Turkey. On the other hand, the British still loom large in the consciousness of those in the region because of past colonial history, exploitation of oil resources, recent wars and close defence, diplomatic and royal links to the area. In the case of Palestine, Britain has the dubious distinction of being the last colonial power in charge of “mandate Palestine”, the territory ceded by the Ottoman empire to UK control under the auspices of the League of Nations and the United Nations. The British evacuated in 1948, leaving behind no new structures of government and handing the situation over to the UN.

So can Britain grant independence to Palestine now?

No, despite the historical legacy. But the British willingness to adopt the policy of Palestinian “independence” does have some symbolic force, and the US may follow suit in time. Cameron’s “declaration” of the desirability of a future Palestine nation state isn’t as powerful as one of his predecessor’s proposal for a “Jewish homeland” back in 1917, but it does carry an echo of that Balfour Declaration, a document still the subject of argument, interpretation and debate.

Is Cameron’s policy on Palestine now more “progressive” than Labour?

Arguably yes, and there is a deep irony here. Under Jeremy Corbyn’s leadership of Labour the policy was to recognise Palestine as a nation state “immediately” upon the election of a Labour government. Sir Keir Starmer quickly reversed that and re-adopted the traditional “two state” under a peace deal line. Now Lord Cameron has gone further (though not as far as Corbyn did) and has left Starmer a little behind. Official policy set out last October stated they will “work alongside international partners to recognise the state of Palestine alongside the state of Israel, as part of efforts to contribute to securing a negotiated two-state solution.”

More recently, Labour MP Wayne David, the shadow minister for the Middle East and north Africa, said: “We will recognise the state of Palestine at a point which will help the peace process once negotiations between Israel and Palestine and the others are taking place.”

By contrast, Cameron doesn’t seem to place peace talks as a necessary pre-condition for recognition. So now the Tories are more “pro-Palestine” than Labour, albeit at the margins.

Why is Cameron saying these things?

Despite the record, we can’t entirely rule out the possibility that he actually believes them and is genuinely moved by the plight of the Palestinian people (without sliding into antisemitism). Do not forget that it was Cameron who, shortly after he became prime minister in 2010, criticised a previous Israeli blockade: “Gaza cannot and must not be allowed to remain a prison camp. People in Gaza are living under constant attacks and pressure in an open-air prison.”

Whether Cameron is doing so as an outrider for the Americans seems doubtful from his emphasis that the UK runs its own “sovereign” foreign policy. However, it is also unthinkable that British diplomats didn’t consult their counterparts and, if so, the Americans raised no objection strong enough to prevent the initiative. Cameron himself points out that after he put his ideas about the recognition of Palestine forward the “Americans announced that they were re-examining their policy and looking at options to see how recognition could best play a part in bringing about a two-state solution”.

What are the implications for British electoral politics?

For better or worse, the whole issue of Palestine and the war in Gaza will have a minimal impact on the general election. Some people on the left and in Muslim communities may feel strongly enough about the way Labour, in particular, has handled the issue to persuade them to withhold their vote or switch it to the Greens, Lib Dems or independents. But there are not enough of them living in relevant marginal constituencies to make much difference. The closest parallel would be the present Rochdale by-election and previous individual seats at general elections where George Galloway and the then Respect party made some impact, but with no great national consequence.

The other example on the national level would be the notable swings in certain seats from Labour to the Liberal Democrats at the 2005 general election, held in the shadow of the war in Iraq. According to the definitive study of the 2005 general election, Labour found it especially hard to hold its vote in Muslim seats, but “this sharp decline in Labour’s vote in constituencies with a large Muslim constituency clearly benefitted the Liberal Democrats but provided no succour to the Conservatives at all; the latter actually lost ground somewhat in constituencies with the largest Muslim communities”.

The Muslim vote is bigger these days as, more arguably, is that of stereotypical leftist students, but the prospective impact on typical Con-Lab marginal seats seems minimal.

The more concerning long-term trend, if it becomes so, would be a communalisation of UK voting loyalties on ethno-religious lines, with all the divisions that would entrench.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments