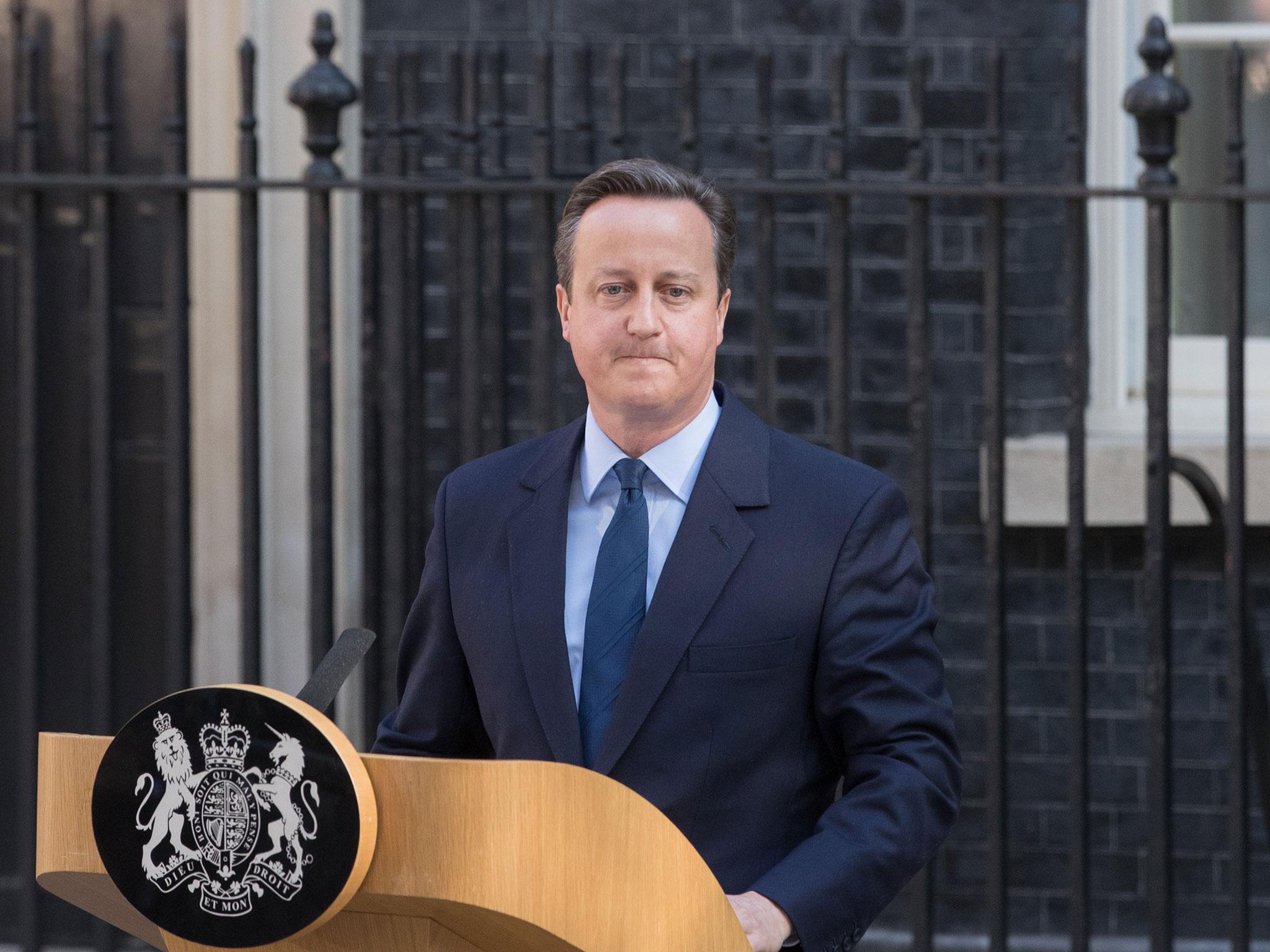

Why David Cameron may never be able to make a comeback

He’s been in the political wilderness since the Brexit referendum and, writes Sean O'Grady, Cameron’s reported refusal to chair a climate conference shows he’ll probably stay there – doomed by his one colossal mistake

Few political reputations have sunk so low and as quickly as that of David Cameron. We all know why. Almost four years after the 2016 Brexit referendum, he is still something of an embarrassment, even to himself. There are reports that he was asked by Boris Johnson to chair the COP26 environmental summit in Glasgow this November, but all Cameron could say was “too soon”. Now that the UK really has left the European Union, any remaining hope that what is regarded as his abiding disastrous legacy might be reversed have evaporated.

Obviously pro-Europeans and what was left of the centrist wing of his party resented his unforced error of the 2016 vote (in their view). Yet Cameron is treated with contempt universally, even by those who have profited from his mistakes. Dominic Cummings, now the most powerful man in government (some claim), and the brains behind the 2016 referendum win and the 2019 general election, derides Cameron’s decision to hold the EU referendum in his celebrated blog: “Cameron never had to offer the referendum in the first place. His sudden U-turn was a classic example of how his Downing Street operation lurched without serious thought in response to media pressure, not because of junior people but because of Cameron himself and his terrible choice of two main advisers.” His rudeness towards Cameron doesn’t end there – he “did not understand many basic features of how the world works”. For his part Cameron labelled Cummings a “career psychopath” and banned him from Whitehall during the coalition government. We all know, too, that Boris Johnson regards his fellow Old Etonian as a “girly swot”.

Danny Dyer put things most pithily on Good Evening Britain a couple of years ago, and many felt he spoke for the nation: “So what’s happened to that t*** David Cameron who called it on? Let’s be fair, how come he can scuttle off. He called all this on, where is he? In Europe, in Nice, with his trotters up. Where is the geezer? I think he should be held to account for it. T***.”

Cultural commentators stressed the critical importance of that second “t***” in Dyer’s condemnation.

Apart from one brief rumour in November 2018 that he fancied coming back as Theresa May’s foreign secretary. Cameron has stayed in his infamous £20,000 “shed”. Since leaving office he has busied himself with charity work and his memoirs, For The Record. Even those have been trolled. A few months ago, when they were launched, the book was given some satirical placement in one Waterstones’ window, plonked next to titles such as Posh Boys, Heroic Failure and Why We Get The Wrong Politicians.

It is still going on. Undertaking essential research for this article, the author popped into his local bookshop and was unable to find a copy; not in Autobiography, nor New Books nor Politics. I asked the assistant who said she thought they had it, but it was kept in a storeroom at the back. She asked me if I wanted a paper bag for it, as if I was about to emerge on to the High Street with a copy of Razzle. I could only answer that I wasn’t ashamed of being seen with Cameron’s mea culpa. Though many would be.

It is difficult to believe, at this distance, that it was Cameron who led his party back to power in 2010 after 13 years in the wilderness; won the first Conservative overall majority in decades in 2015; and who presided over a government that, for all its austerity and misjudgments, also had the kind of socially liberal instincts that many had judged incompatible with Toryism. In his “hug a hoodie” and “hug a husky” phases he passed for a progressive. At any rate he was, before The Fall, at least respected as a winner and competent. No longer.

In a survey by the University of Leeds of the nation’s political experts undertaken a few months after the 2016 referendum, Cameron came 11th out of 13 post-war premiers, with Clement Attlee and Margaret Thatcher, as usual, topping the poll and Anthony Eden (Suez) at the bottom. Nearly 90 per cent of those polled cited the EU referendum as Cameron’s greatest failure – with one claiming it was the greatest defeat of any prime minister “since Lord North lost America”.

One of Cameron’s few consolations must be that Theresa May may rank even lower than he does. What are the prospects for a Cameron revival? Poor.

There is usually something of a cycle to these things. Premiers usually leave office as failures, at the nadir of their fortunes. Then, when time heals wounds and adds perspective, and some “myth busting” hobbyists get to work their reputations gradually improve. Stanley Baldwin might be a good example of that – his complacency about Hitler later balanced by an appreciation of his domestic record and his efforts to hold British society together through the bitterness so the interwar years. Harold Wilson, like Baldwin an electoral maestro in his day, was soon trashed after he left office in 1976, with both the social democrats and leftists in his cabinets truing against him.

Only recently have his remarkable feats – such as holding the Labour party together over Europe, economics and defence, and keeping it in power, come to be appreciated more fully. Margaret Thatcher’s reputation, unusually, stood proud for decades after her downfall in 1990, but as her brand of economics has fallen out of fashion so has she. Tony Blair remains despised by many in his own party. One of the current leadership candidates, Lisa Nandy has been lambasted for having held a meeting with him during one of the attempted coups against Jeremy Corbyn. Ramsay Macdonald (who “betrayed” Labour by joining a coalition with Conservatives in 1931, and became a byword for treachery) had to wait until the 1980s to see his critical decisions reassessed sympathetically.

Yet there are some prime ministerships which are so marked by one colossal disaster – one that failed to yield any long-term benefits whatsoever – that their reputations will forever be mired. Neville Chamberlain over appeasement and Munich; Eden on the Suez fiasco; and, so far as we can see now, Cameron on Brexit are examples of figures forever condemned to live in the dark shadow of their own misjudgments. In possession of all the facts, with no shortage of expertise an advice to draw upon, they made decisions that hugely damaged the national interest. The irony for Cameron is that even if Brexit becomes the lavish success its progenitors promise he can’t even benefit from because he led the “In” campaign. For Cameron, still a mere 53, it seems it will always be “too soon” to return to politics.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments