What is the significance of Charles and Camilla’s visit to Kenya?

In the run-up to the 60th anniversary of Kenya’s independence, the royal couple are making their first visit to a Commonwealth nation since Charles acceded to the throne in 2022. Sean O’Grady explains the wider context of the trip both for Kenya and for the UK

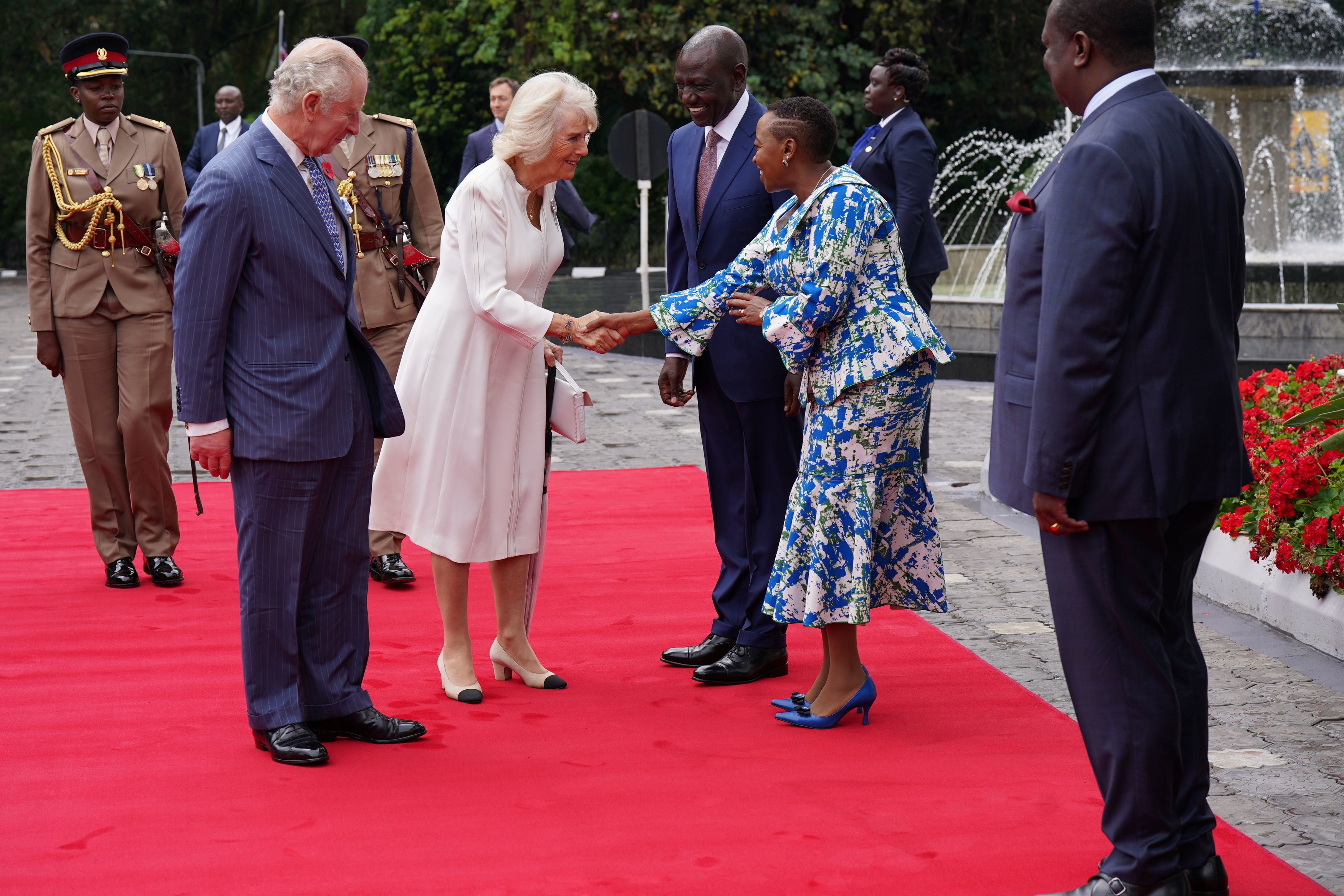

Charles and Camilla’s visit to Kenya is their fourth official overseas trip, and a timely reminder of how important international “soft power” is to the UK in the post-imperial, and now post-Brexit, era. The four-day visit includes an act of remembrance for the victims of the colonial administration, as well as a state banquet and events with charities and business. As King and Queen, the couple play a unique role in projecting British influence – and at a time of relative national decline, that matters.

What’s the point of the visit?

To improve relations with an important Commonwealth nation, and a strategically important regional partner in an area that is troubled by active Islamist militants and contains at least one failed state – Kenya’s neighbour Somalia. Periodic terror attacks and refugee movements into Kenya have also added to the instability in the region. The timing of the visit is propitious, as it takes place close to the 60th anniversary of Kenya’s independence or uhuru (freedom), which was declared on 12 December 1963.

Buckingham Palace says the visit will “acknowledge the more painful aspects of the UK and Kenya’s shared history, including the Emergency (1952-1960)”, adding: “His Majesty will take time ... to deepen his understanding of the wrongs suffered in this period by the people of Kenya.”

The visit, like all such official activities, will have been planned on the advice of ministers.

So will Charles apologise for the excesses of British colonial rule?

No. An apology may be appropriate, but some in government might feel that it would attract claims for reparation from those directly and indirectly affected by the brutality of the colonial administration and the British-led forces tasked with crushing rebellions and the independence movement.

The British government previously agreed to pay some £20m in compensation for the victims of the emergency in the 1950s, and considers the matter closed. That was, after all, a period when such leaders as Jomo Kenyatta, who later became president, were routinely locked up or exiled by the UK, invariably to no lasting effect. A wreath-laying ceremony on Tuesday at the Kenyan national cemetery commemorated the more than 1,000 people executed during the Mau Mau rebellion.

This is the usual pattern, isn’t it?

Yes. For example, in 1997, when the late Queen visited the site of the 1919 Jallianwala Bagh or Amritsar massacre in India, where British troops had shot dead more than 500 protesters, she stopped short of saying sorry. She instead spoke of “difficult episodes” in the imperial era: “It is no secret that there have been some difficult episodes in our past. Jallianwala Bagh is a distressing example.”

In the same vein, a decade ago, Elizabeth II also came the closest that the British state has ever come to apologising for 800 years of cruel quasi-colonial rule in Ireland. During the first such royal visit since before the First World War, the Queen deployed a memorable turn of phrase: “It is a sad and regrettable reality that, through history, our islands have experienced more than their fair share of heartache, turbulence and loss ... With the benefit of historical hindsight, we can all see things which we wish had been done differently, or not at all.”

What about the rest of the Commonwealth?

The King will be 75 next month, and Camilla is 72, so there’s no chance of any arduous global tours to rival the late Queen and Prince Philip’s post-coronation schedule between December 1954 and May 1954. That odyssey covered the West Indies, Australasia, Asia and Africa, and traversed some 44,000 miles, with the royal yacht Britannia adding to the grandeur. Mind you, the British still had an empire in those days.

Whether the following independent nations will ever see their head of state and his queen set foot on their soil remains to be seen: Antigua and Barbuda, Australia, the Bahamas, Belize, Canada, Grenada, Jamaica, New Zealand, Papua New Guinea, St Kitts and Nevis, St Lucia, St Vincent and the Grenadines, the Solomon Islands and Tuvalu, Australia, Canada, New Zealand, Papua New Guinea.

Lots of air miles there, and quite the itinerary, but Camilla is rumoured to dislike long-haul flights. The Prince and Princess of Wales may have to take up the slack, or else risk losing even more of the old “realms and possessions” across the seas.

How are the King and Queen doing?

Fine. The King, under his former title of Prince of Wales, has visited Kenya four times before this trip. (The first, in 1971, was shortly before he first met the then Camilla Shand.) He’s had a long apprenticeship in royal diplomacy and, to be fair to him, rarely makes a faux pas.

His most famous gaffe was probably in the form of his remarks about China’s gerontocratic leadership consisting of “ghastly old waxworks” during the handover of Hong Kong in 1997. The recent trips to Germany, Romania and France went very well, and the House of Windsor is still a useful arm of “soft power” for Britain, though the late Queen was always going to be a tough act to follow.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments