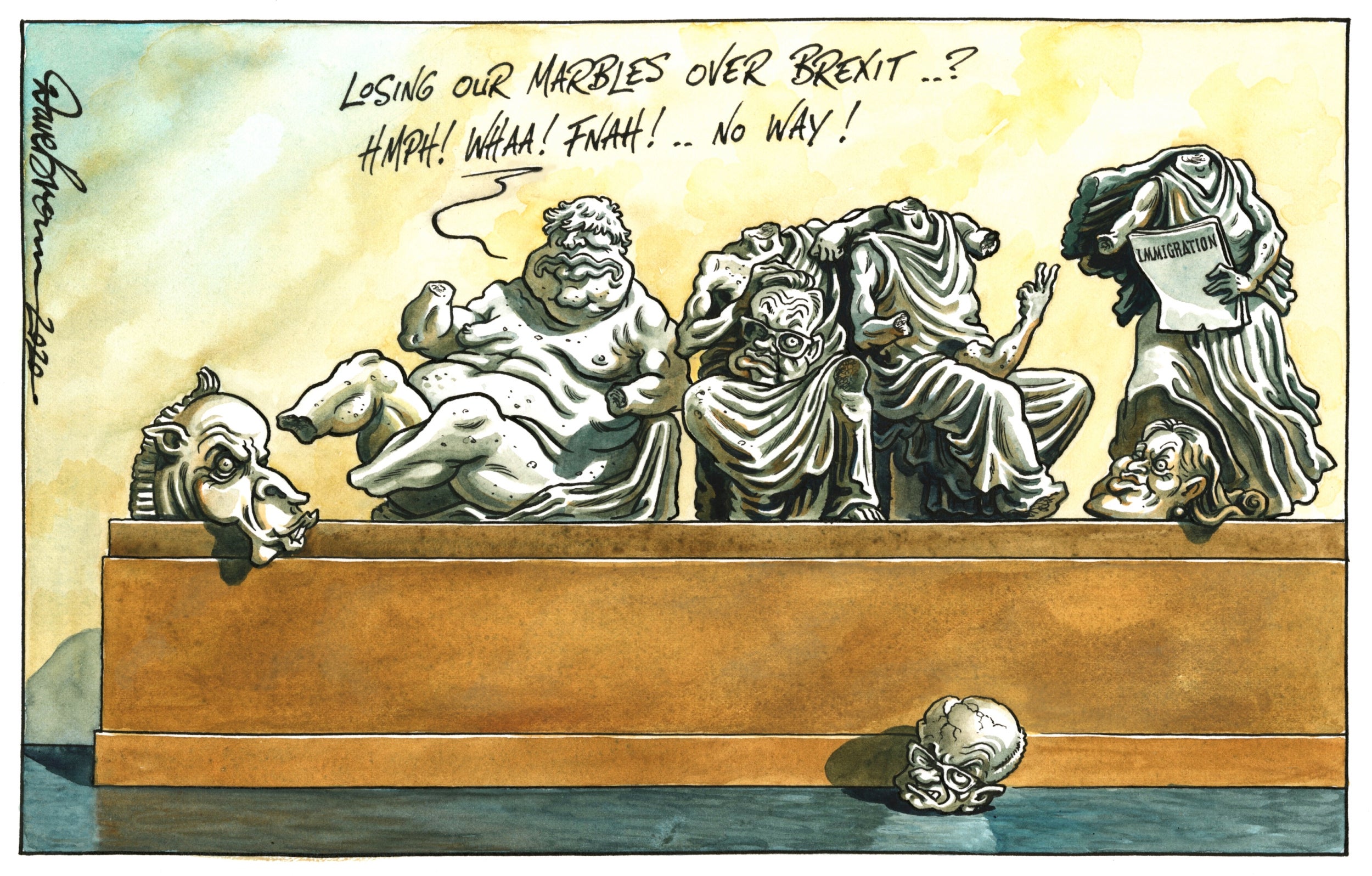

Why a Brexit trade deal will be so difficult for Boris Johnson to strike

The problem, writes Sean O'Grady, all comes down to trust

Although it’s probably not as lively a topic of popular conversation as the merits of VAR or events at the Brits, the question about whether the UK can have a “Canada-style” trade agreement with the EU is probably the more portentous.

It seems that the UK cannot have such a deal, as it would now like, because the EU won’t agree to it. This is the case even though the EU’s chief negotiator, Michel Barnier, once proposed precisely that option to the EU’s Council of Ministers at a key meeting back in 2017.

In a leaked PowerPoint slide now circulating on Twitter, there is a “staircase” of different options, from full membership through various degrees of integration (Norway, Switzerland, Ukraine, Turkey), down to the more modest free trade agreements the EU has concluded with South Korea and Canada. These allow for great freedom for the “third country” to pursue its own trade policy and general economic arrangements. The Johnson government likes the sound of this because it would preserve the UK’s tariff- and quota-free access to the EU’s huge markets, while allowing the UK government freedom to frame internal policies that would boost British competitiveness, both with the EU and the wider world.

Sometimes this is portrayed as a “race to the bottom”, shredding worker rights and environmental protections. But this is not necessarily the case, as it might also include ambitious subsidies to develop new hi-tech industries, say, or lowering taxation on business or liberalising regulations.

The No 10 Twitter account has re-published the slide, with the implication that the EU is reneging on that earlier offer (though it was never formally made, let alone agreed with, the British government). The implication is that the EU has been acting in bad faith. Maybe so, and maybe inadvertently, because the EU might have supposed, based on ministerial pronouncements, that a general UK commitment to a “level playing field” would stop Britain trying to compete unfairly with the EU.

The “level playing field” has become a bit of a Great War battlefield recently – muddy and entrenched. Here, the EU is able to claim that the UK is also insincere in its commitments to the “level playing field”, which were solemnly enshrined in the UK-EU political declaration last year. Though not legally binding, the declaration pledges:

“The parties agree to develop an ambitious, wide-ranging and balanced economic partnership. This partnership will be comprehensive, encompassing a free trade agreement, as well as wider sectoral cooperation where it is in the mutual interest of both parties.

“It will be underpinned by provisions ensuring a level playing field for open and fair competition.”

And: “Given the Union and the United Kingdom’s geographic proximity and economic interdependence, the future relationship must ensure open and fair competition, encompassing robust commitments to ensure a level playing field. The precise nature of commitments should be commensurate with the scope and depth of the future relationship and the economic connectedness of the parties. These commitments should prevent distortions of trade and unfair competitive advantages. To that end, the parties should uphold the common high standards applicable in the Union and the United Kingdom at the end of the transition period in the areas of state aid, competition, social and employment standards, environment, climate change and relevant tax matters.

“The parties should in particular maintain a robust and comprehensive framework for competition and state aid control that prevents undue distortion of trade and competition; commit to the principles of good governance in the area of taxation and to the curbing of harmful tax practices; and maintain environmental, social and employment standards at the current high levels provided by the existing common standards. In so doing, they should rely on appropriate and relevant Union and international standards, and include appropriate mechanisms to ensure effective implementation domestically, enforcement and dispute settlement. The future relationship should also promote adherence to and effective implementation of relevant internationally agreed principles and rules in these domains, including the Paris Agreement.”

Yet now, only a few weeks later, the British chief negotiator, David Frost, puts a different gloss on things: “It is central to our vision that we must have the ability to set laws that suit us – to claim the right that every other non-EU country in the world has. So to think that we might accept EU supervision on so-called level playing field issues simply fails to see the point of what we are doing. That isn’t a simple negotiating position which might move under pressure – it is the point of the whole project. That’s also why we are not going to extend the transition period beyond the end of this year. At the end of this year, we would recover our political and economic independence in full – why would we want to postpone it? That is the point of Brexit. In short, we only want what other independent countries have.”

“Other countries” such as Canada, for example. To this, the EU responds that Canada is thousands of miles away, and, implicitly, is nowhere near such a close competitor and threat to the European order as a maverick free-market UK would be – “Singapore-on-Sea” is an unwelcome neighbour.

While Johnson and his team keep promising to retain “high standards”, even higher than those in the EU perhaps on issues such as live transport of livestock, the concept of a “level playing field” is not a precise one, and people can take different views on whether, say, mandatory worker-directors amount to higher labour market standards or not. Is the EU working time directive stronger or weaker if it is replaced by a new UK law broadly requiring employers to treat workers well and to offer them flexible working hours, including different employment statuses?

In addition, there seems no agreement on what form arbitration over such arguments might take.

When the UK makes vague promises about “high standards” the EU smells a rat. When the EU makes vague demands about “high standards”, the UK smells a rat. The reason, in other words, why this free trade agreement will probably be unusually difficult to conclude is the lack of trust between the two sides; and the lack of any legal mechanism to make sure that both sides keep to their (vague) undertakings. This, by the way, also goes for the UK-EU withdrawal agreement, which has the standing of an international treaty, but could easily unravel over the new GB-Northern Ireland economic border.

In the end, the EU’s horror of tariffs and quotas, and the UK’s horror at losing easy access to its largest export market by far might propel both sides to compromise. The talks will probably go right to the wire – the end of December. Yet, if they are sincere in what they say now, the talks might as well be called off, and the UK and EU agree to go their separate ways governed only by the weak strictures of the World Trade Organisation. In which case, both sides will be applying taxes on imports and other obstacles to trade and market access. Like all divorces, it would turn very nasty indeed.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments