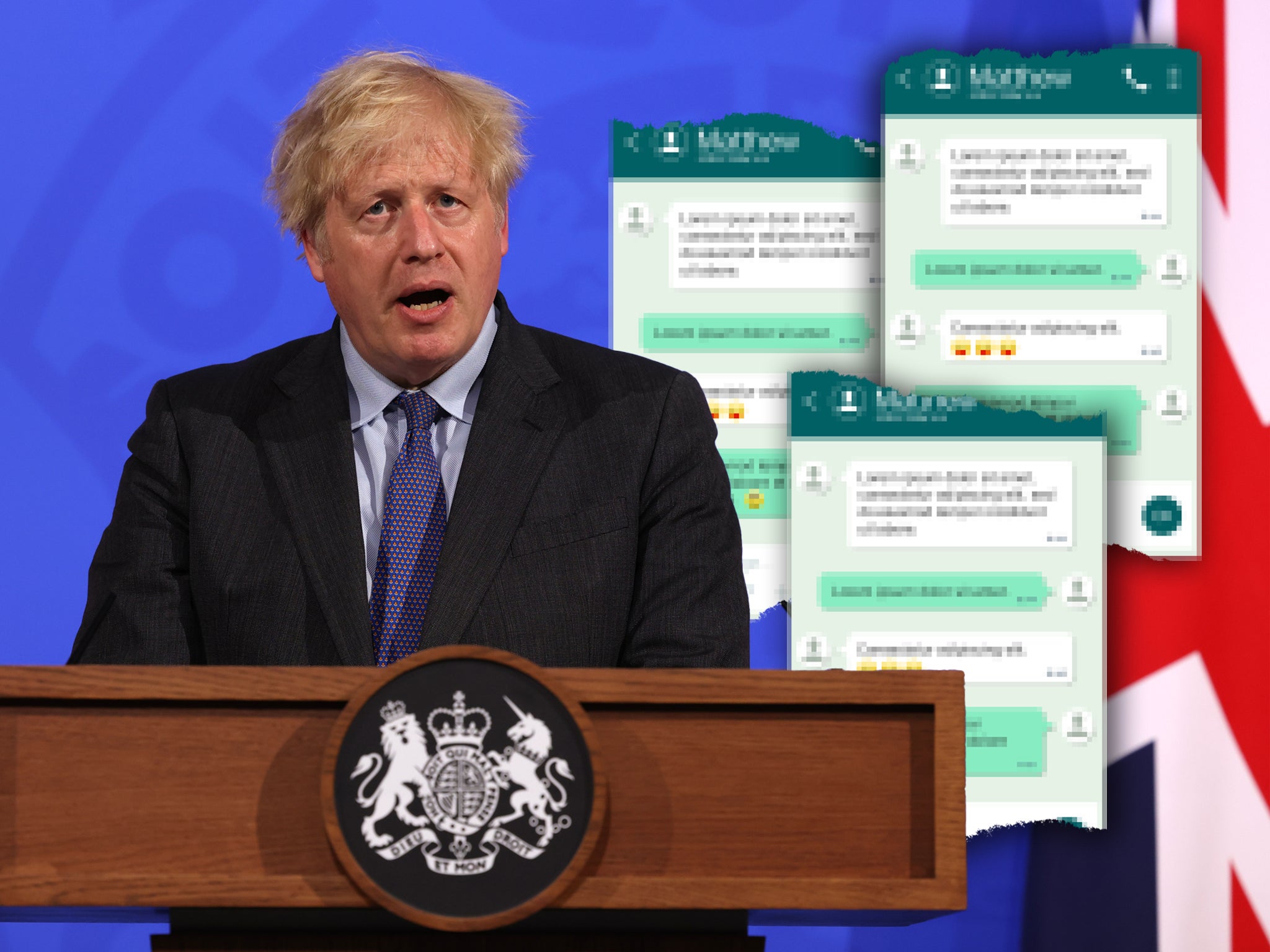

What’s at stake in a legal battle over the Covid WhatsApps?

Now that Boris Johnson has handed the material requested by the Covid inquiry to the Cabinet Office, the ball is in Rishi Sunak’s court, writes Sean O’Grady

It seems inevitable that a judicial review will take place on the matter of whether the Cabinet Office can redact evidence demanded from the government by Baroness Hallett’s Covid inquiry. Boris Johnson has released his diaries, WhatsApp messages and other material unredacted – thus avoiding any possible criminal sanction for withholding or destroying evidence. How much of it Johnson wants the inquiry to see is unclear, but he seems content to allow the Cabinet Office to deal with it.

There is talk of a “cover-up”, in effect by Rishi Sunak, who it is suggested is conspiring to use government lawyers and the prestige of his office to prevent the disclosure of the material to the inquiry, even on a confidential basis.

Johnson’s surprise move adds to the pressure on Sunak and the Cabinet Office to abandon its legal challenge and accede to Hallett’s request. “Mr Johnson urges the Cabinet Office to urgently disclose [the material] to the inquiry,” said a statement from the former PM’s spokesperson. “Mr Johnson ... is perfectly happy for the inquiry to have access to this material in whatever form it requires.”

What does Johnson have to lose?

Perhaps not so much, given he has handed over the requested messages and notebooks in full and unredacted form – material the Cabinet Office has previously said it didn’t have. We can’t know for sure, but we do know from the evidence that has appeared so far (mostly from Matt Hancock, Dominic Cummings, the Sue Gray report and various books) that Johnson was prone to being foul-mouthed, callous, self-interested and blase about breaking the lockdown rules he had imposed on everyone else.

He is widely reported, for example, to have declared that he would rather “let the bodies pile high” than have another lockdown; maybe he has now decided to publish and be damned? In extremis, renewed disgrace might dent his earning power. Ouch.

And what does Sunak have to hide?

An intriguing question. Sunak was chancellor throughout the pandemic, and was aggressively proactive in supporting the economy, doing “whatever it takes” as the soundbite went. The furlough scheme was especially effective, as were the various loans and all manner of tax cuts and subsidies deployed, as well as an ultra-easy money policy adopted by the Bank of England, underwritten by Sunak’s Treasury. The chancellor’s grip on detail and his compassionate demeanour went down well with the public, and contrasted sharply with the approach of some of his colleagues. It’s not too much to claim that Sunak had “a good war” during Covid.

However, it wouldn’t be surprising if he were rather more equivocal behind the scenes; if he was involved in balancing Covid mortality against the economic damage from inflated national debt, some callous-seeming remarks might have been made. Nor can we rule out the possibility that Sunak’s impeccable manners didn’t carry over to his private communications and thoughts, about either his colleagues or the great British public.

How will the case go?

It’s axiomatic, but often forgotten, that such cases are argued on points of law rather than morality or politics. The law is perfectly clear: the 2005 Inquiries Act grants sweeping powers to the chair to demand all types of evidence that is of potential interest. What they do with the material is also a matter for the inquiry team. Downing Street and the Cabinet Office argue: “It would not be appropriate to compel the government to disclose unambiguously irrelevant material given the precedent that it would set and the adverse impact it would have on the right to privacy.” They maintain that it’s normally up to the government to redact information, and that the constitutional principle of collective cabinet responsibility might otherwise be breached.

Johnson says it’s all “nonsense”, while some of his allies say it’s part of a plot to further destroy his career.

None of those arguments is particularly compelling in the face of a very clear statute that parliament, in the acrid aftermath of the Iraq war, plainly intended as a measure to provide independent inquiries with the power to get to the bottom of things. Not only has Hallett the absolute lawful discretion to read what she wishes; with the exception of matters of national security, she also has the discretion to publish extracts as she deems fit in order that lessons can be learned.

What do the opposition parties say?

They can’t really lose with this one. The Liberal Democrats’ health spokesperson, Daisy Cooper, said that a failure to hand over everything requested would “make a mockery of this whole process and would be yet another insult to the millions of bereaved still waiting for justice”. Angela Rayner, the deputy Labour leader, claimed that “while other countries across the world have already finalised their inquiries into the pandemic, it is essential that ministers now comply with their obligations so the public can get to the truth.”

What’s the worst-case scenario?

For Johnson, Sunak, and others closely involved at the time – such as Hancock, Cummings, Chris Whitty, Patrick Vallance, Nadhim Zahawi and Simon Case – there could be enormous embarrassment and reputational damage. Opponents will pounce on the evidence to their own advantage. This is certainly what happened when a journalist decided to take Hancock’s WhatsApp messages to a newspaper, and when Cummings released his own documents and recollections.

If such material were to be leaked at a critical point in an election campaign, for example, under a “public interest” defence, it might have grave political consequences for the Conservatives.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments