If AI really is so dangerous, why is there such little regulation?

From fake audio of Keir Starmer swearing at an aide to question marks over recent election results in Slovakia, artificial intelligence is already showing its teeth in the political arena. So, asks Sean O’Grady, where are the laws to protect democracy?

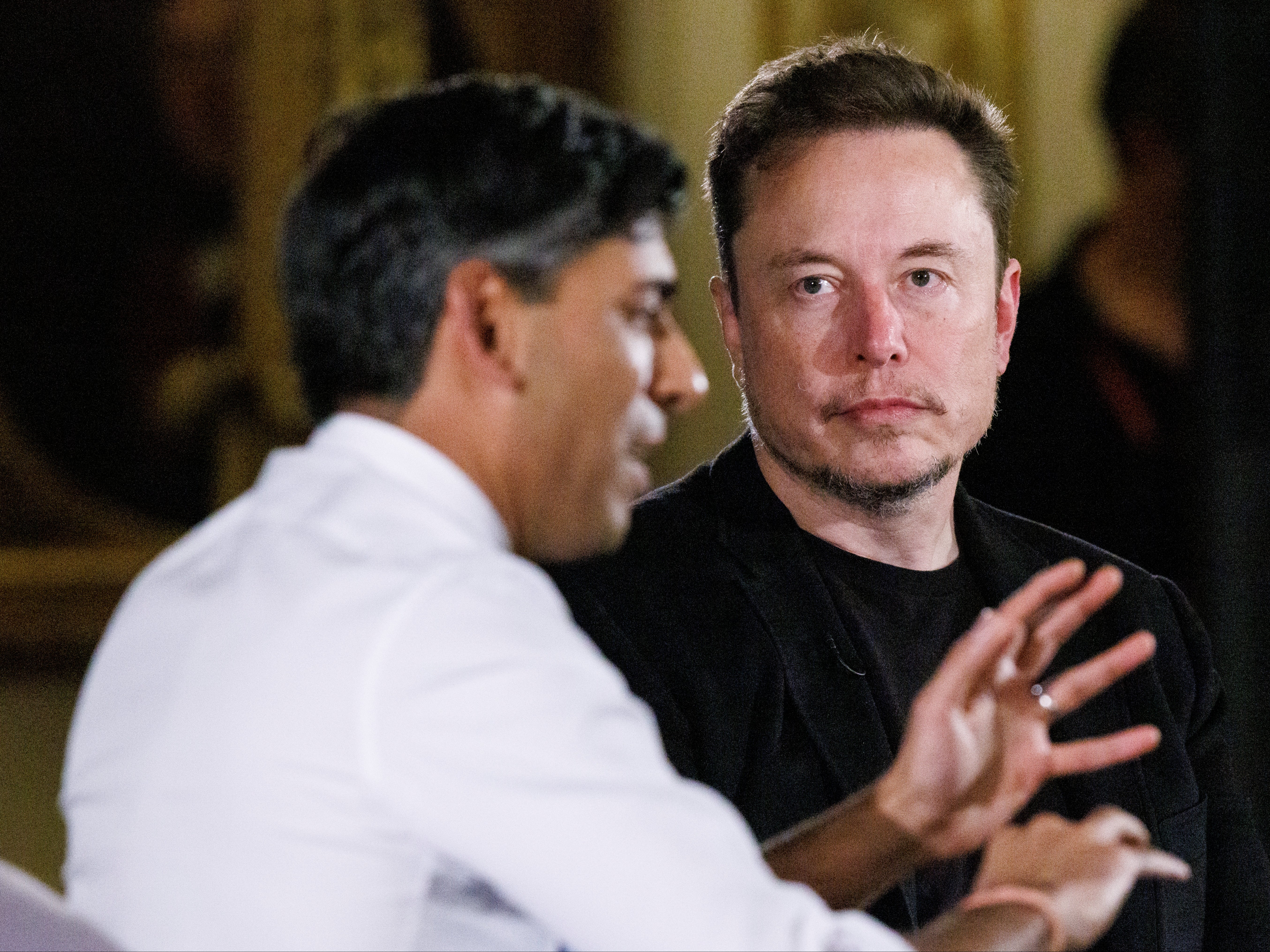

At the UK-hosted artificial intelligence (AI) safety summit this week, Elon Musk, who understands such things, warned AI is “the most disruptive force in history”.

Even though the impact of profound AI, far exceeding human intelligence, may be on balance highly beneficial to humanity and might even abolish work, it has its “magic genie” problems. One of those is certainly the effect AI can have on free elections in democratic societies (and indeed those in flawed semi-democracies).

Musk himself identified deepfake videos that can be highly misleading and “more impressive than the real ones”. Yet even now, at the dawn of AI intervening in the political process, there is remarkably little regulation of such phenomena by the likes of the Electoral Commission or Rishi Sunak’s opposed AI Safety Institute.

Next year, the UK, India, the EU, and the US are set to hold elections and will witness unprecedented amounts of AI-inspired fakery, feeding on a conspiracy culture and hyper-partisan electorates ready to believe the most improbable fibs about their enemies. Russian interference in elections will be much easier.

Musk points out that AI capability is growing each year and that the government isn’t used to moving at that speed. He’s right…

What is different about AI?

Obviously, human history is replete with propaganda, hoaxes, forgeries and deception, applied to every aspect from the art world to criminal fraud to political intrigue.

Even William Shakespeare was in the business of twisting the recent history of his Tudor bosses. The Zinoviev letter, the Protocols of the Elders of Zion and Donald Trump’s lies about a stolen election are just some of the more notorious examples of such activities.

What’s obviously different now is that AI can produce extremely realistic hoaxes, such as deepfake videos, bogus documents, doctored news footage and the like.

When that can be disseminated globally in a matter of seconds via social media, and sometimes picked up mistakenly by mainstream media, then the truth is soon lost among the thickets of conspiracy theories. As the old saying goes, a lie can be halfway around the world before the truth gets its shoes on.

Has AI already been used to create fakes in the UK?

Yes. For example, just before the Labour conference began, an audio recording of Keir Starmer swearing at an aide emerged on X (formerly Twitter) and began to be widely shared.

It had an authentic sort of feel to it, as if surreptitiously caught on a smartphone in some conference coffee area, with the hubbub of chatter behind. There were some oddly repetitive sections that made one wonder about it, as well as some doubt as to whether this was Starmer’s style. Most tellingly it seemed to have been first posted by an anonymous bot-like Twitter user. It was soon revealed as fake, but not before it had distracted attraction from the real news and inflicted minor damage on Starmer’s reputation (though some liked his spirit and shared his impatience with incompetence). The government condemned the “tape” as bogus and it was taken down. For British politics, it was a warning shot: AI may well have helped make the tape sound realistic.

Has AI made an impact on elections?

The recent elections in Slovakia suffered from a very similar audio hoax – presumably because video footage needs to synch moving images of mouth movements and gestures with sound – still a tricky task. The fake audio was posted to Facebook. It featured two voices: one was Michal Simecka, who leads the liberal Progressive Slovakia party; and the other purported to be Monika Todova from the daily newspaper Denník N. They appeared to be discussing how to rig the election, partly by buying votes from the country’s marginalized Roma minority. The racist aspect of the scam made it both more effective and more repulsive.

The other trick was that the audio was released during the 48-hour moratorium on campaigning activity immediately before polling day – so refuting the audio was even more fraught. It also exploited a loophole in Meta/Facebook’s rules which only banned deepfake videos, not sound-only files.

In a tight contest, did it make a difference? We cannot know, but Simecka’s pro-Nato party, Progressive Slovakia, lost to the pro-Russian SMER, which campaigned to withdraw military support for its neighbour, Ukraine. Coincidence? Let’s not be conspiratorial…

What about the United States?

Sadly, it is already well under way, albeit more at the satirical end of things. It is, after all, hard to believe when Hillary Clinton apparently trills that “I actually like Ron DeSantis a lot ... He’s just the kind of guy this country needs, and I really mean that.” Similarly, few should be taken in by a snarling Joe Biden telling a trans woman: “You will never be a real woman.” But people can be gullible.

According to DeepMedia, a company working on tools to detect “synthetic media”, there have been three times as many video deepfakes of all kinds and eight times as many voice deepfakes posted online this year compared to the same time period in 2022. It can only get worse.

What could happen?

Elections will be stolen, to the benefit of Russia and other agents – states, terror or criminal gangs – who spy an opportunity to rig an election to gain some form of advantage. Such scandals, if and when uncovered, will further debase trust in democratic institutions, and open the way for yet more chaos.

What can be done to protect against AI being misused?

The tech giants and the AI companies can at least acknowledge the problem, as Musk does, and ban their software from being used to manipulate the images and remarks of politicians and parties. Governments could impose harsh fines on such activities, augmented by international treaties and collective action. The public can be taught how to spot a fraud. People in such an atmosphere may increasingly turn to established trusted sources of curated news and analysis (though the perverse attractions of “alternative” media and the culture of “naive cynicism” seem powerful obstacles to a more rational debate). AI could be used to spot and filter fake news and deepfake videos. But, like all crime, political fraud will be a never-ending cat-and-mouse game between regulators and bad faith actors, and AI will soon be speeding things up considerably.

After the success of the AI summit, it would be nice to think Sunak would announce plans to set a global example and tighten up election laws in the King’s Speech next week. We’ll see.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments