PMQs sketch: Cameron stands strong as Corbyn has to stop himself saying ‘I told you so’

You got the impression that the Labour leader's 33 years in Parliament had been leading up to this vindication

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.It was not, as Mark Durkan of the Northern Irish SDLP remarked, a “moment for soundbites”, but when he wondered aloud if David Cameron would agree that the “hand of history” should now be “feeling someone’s collar” over the Iraq catastrophe, we knew exactly who he meant. It was a nice inversion of Tony Blair’s most celebrated soundbite, and a rare moment of (uneasy) relief in an unrelievedly sombre session.

David Cameron responded to it, as he did to all of the many criticisms of his predecessor-but-one, in the same measured way: “You can’t turn the clock back”. The Prime Minister was in a strange, and strong, position. Iraq was not, after all, Cameron’s war, and such has been the long gestation of the Chilcot inquiry that Cameron has been able to implement most of the report’s recommendations before they were even published or even thought of. As he politely reminded the House, Cameron has instituted a National Security Council, enhanced the role of Parliament, brought the Attorney General directly into decision making, required formal legal advice on going to war, and reverted to formal cabinet committee structures.

Cameron, perhaps feeling some sort of comradeship as his own premiership draws to a close, also chucked a bone to Blair – near-friendless in the Commons – in reminding some of the less sympathetic, such as the SNP’s Angus Robertson, that “you can have all the plans in the world but these are always difficult decisions” about weighing the “balance of risks”. Moreover, Cameron was happy to endorse the “good faith” defence for voting for war in Iraq when requested to do so by former Blair minister Ben Bradshaw. Of course he did – as a fresh backbencher in 2003 Cameron was one such cadet warmonger, as he freely acknowledged. He also admitted, as if to prove the point, that Libya was procedurally impeccable, but still a bit of a disaster. Cameron didn’t explicitly say, “I’m the only person here who knows the loneliness of these decisions”, but that fact hung heavily in the air.

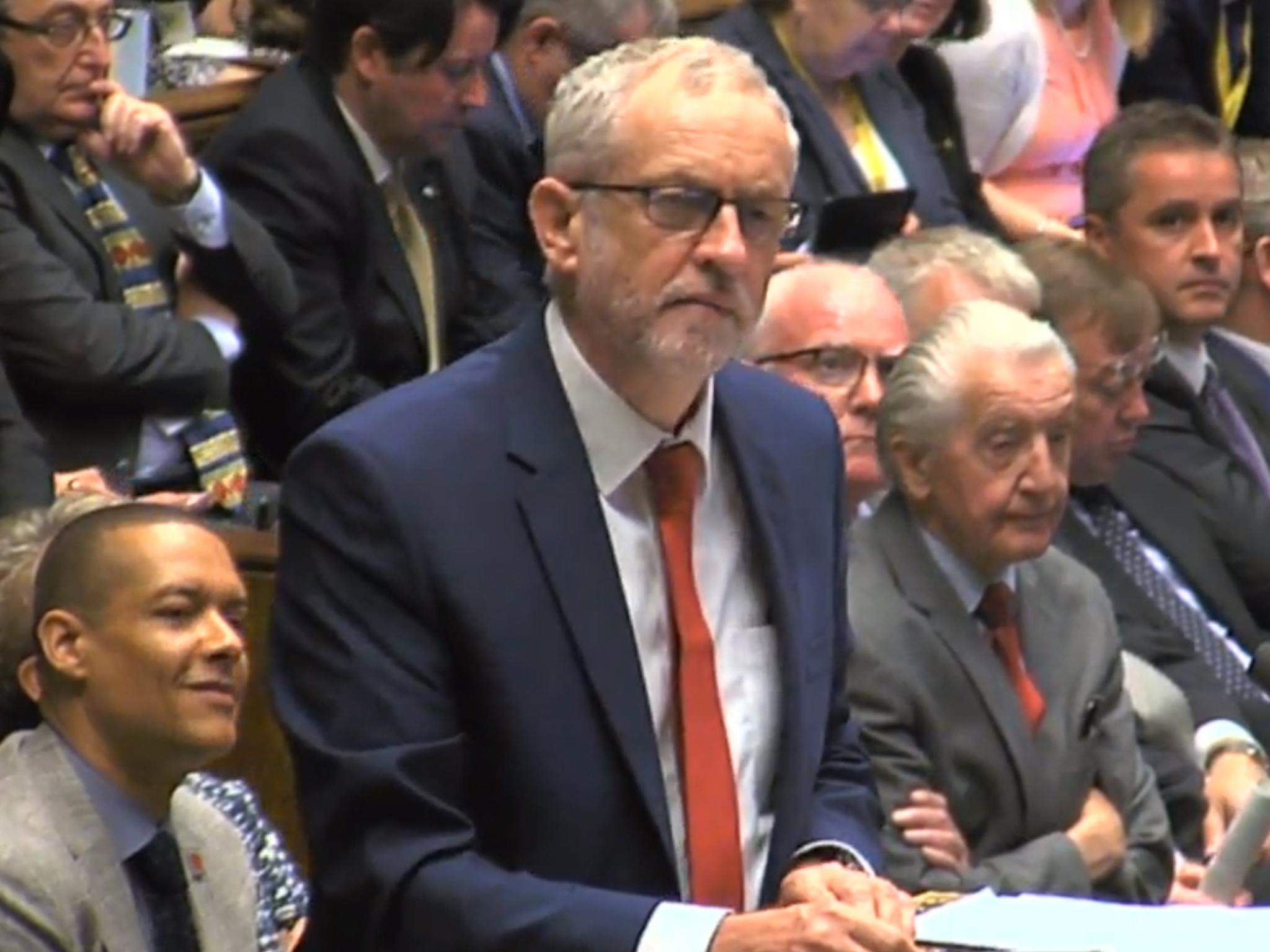

For Jeremy Corbyn it was a rare opportunity to show critics who think his career has been a Bayeux tapestry of dreadful misjudgements that he had been right on this – and they wrong. Indeed, he added, not only had he been justified in following the example of the late and virtually canonised Robin Cook in voting against the Iraq invasion, but that he was one of the very lonely few to campaign in the 1980s against Saddam Hussein’s fascistic regime, when the US and UK were clandestinely arming him. This was a time when Saddam used chemical weapons and murdered shias, Marsh Arabs and Kurds, the crimes that made Blair so determined to get rid of him.

The Leader of the Opposition did his best not to appear to gloat – “no-one takes any satisfaction from this report” – but you got the impression that 33 years in Parliament had been leading up to this vindication. Respect him or not, you cannot claim that, say, Angela Eagle would have been able to command the same moral authority on this one. Corbyn focused on the idea that the Commons “had been misled” in the run-up to war. He could have said that the House had been consciously misled, but he unaccountably pulled that particular punch. Corbyn called for a War Powers Act: Cameron dismissed this as a “legal mess”.

And that was that. The Lib Dem leader Tim Farron, and the Greens’ Caroline Lucas were punchier than Corbyn, Farron emphasising Blair’s “single-minded determination to go to war”, and Lucas demanding a “public apology” from the Conservatives, then in opposition, for voting for war. But they didn’t have any more success in penetrating the Prime Minister’s well-honed defensive shield of compassionate reasonableness. The Tories will surely miss that when he’s gone.

Corbyn was buttressed by a long record of habitual dissent on Iraq which bears out the old adage that even a stopped clock sometimes tells the right time. He acquitted himself adequately, but his performance didn’t persuade his detractors that he has developed the necessary forensic skills as an opposition front-bencher once displayed so formidably by Robin Cook and, as it happens, Tony Blair. I couldn’t help fantasising about how things might have played had Prime Minister Blair still been at the dispatch box facing Mr Corbyn as Leader of the Opposition. I’m not sure who would have won.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments