Margaret Thatcher demanded UK find ways to 'destabilise' Ethiopian regime in power during 1984 famine

Thatcher decided it was wrong to 'jog along' with the Mengistu government, whose human rights abuses greatly exacerbated the famine death toll

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Margaret Thatcher demanded that Britain find ways to “destabilise” the regime which presided over Ethiopia’s disastrous 1984 famine after concluding that British aid was wrongly supporting its “particularly cruel” government, according to previously unpublished records.

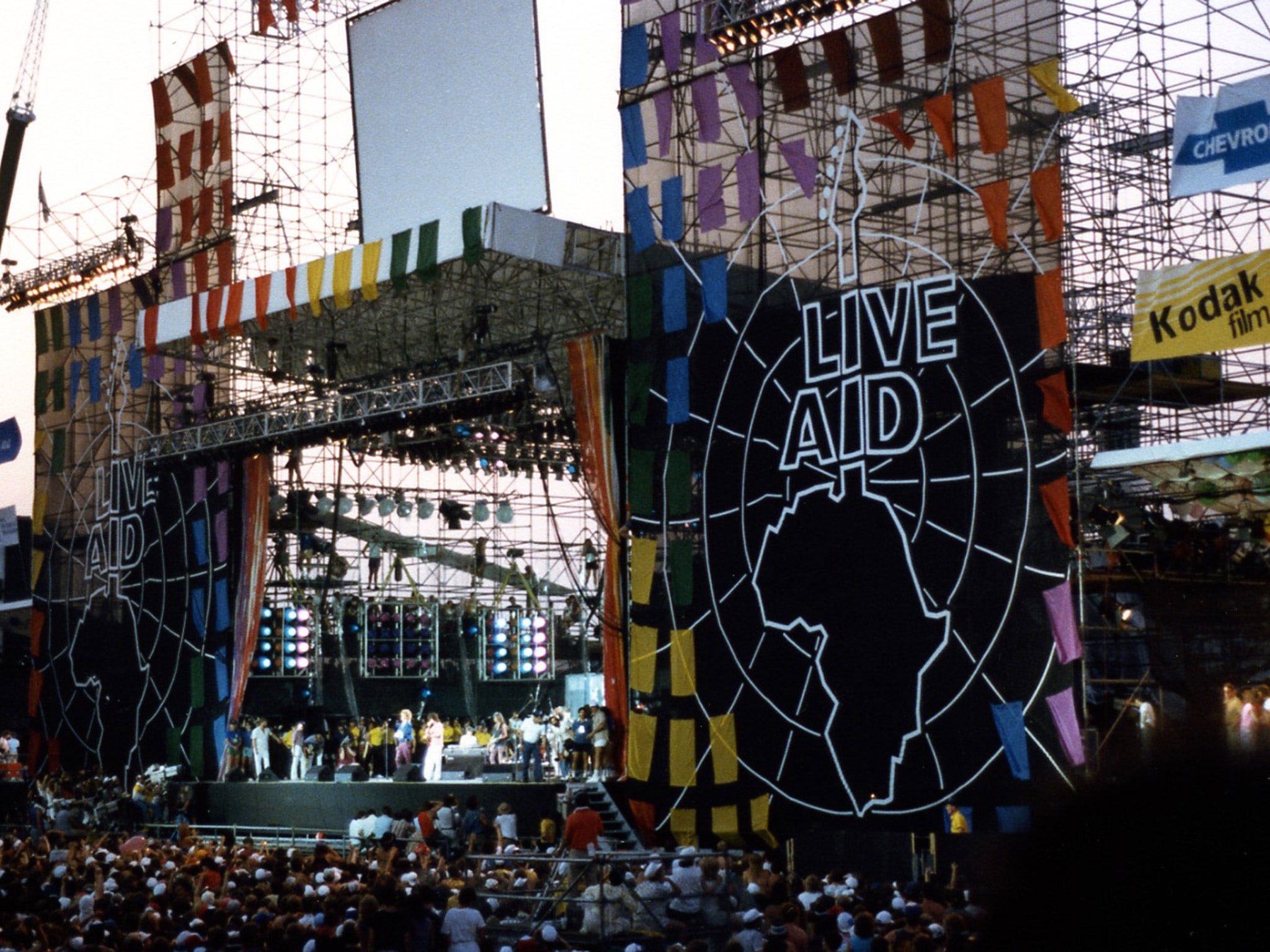

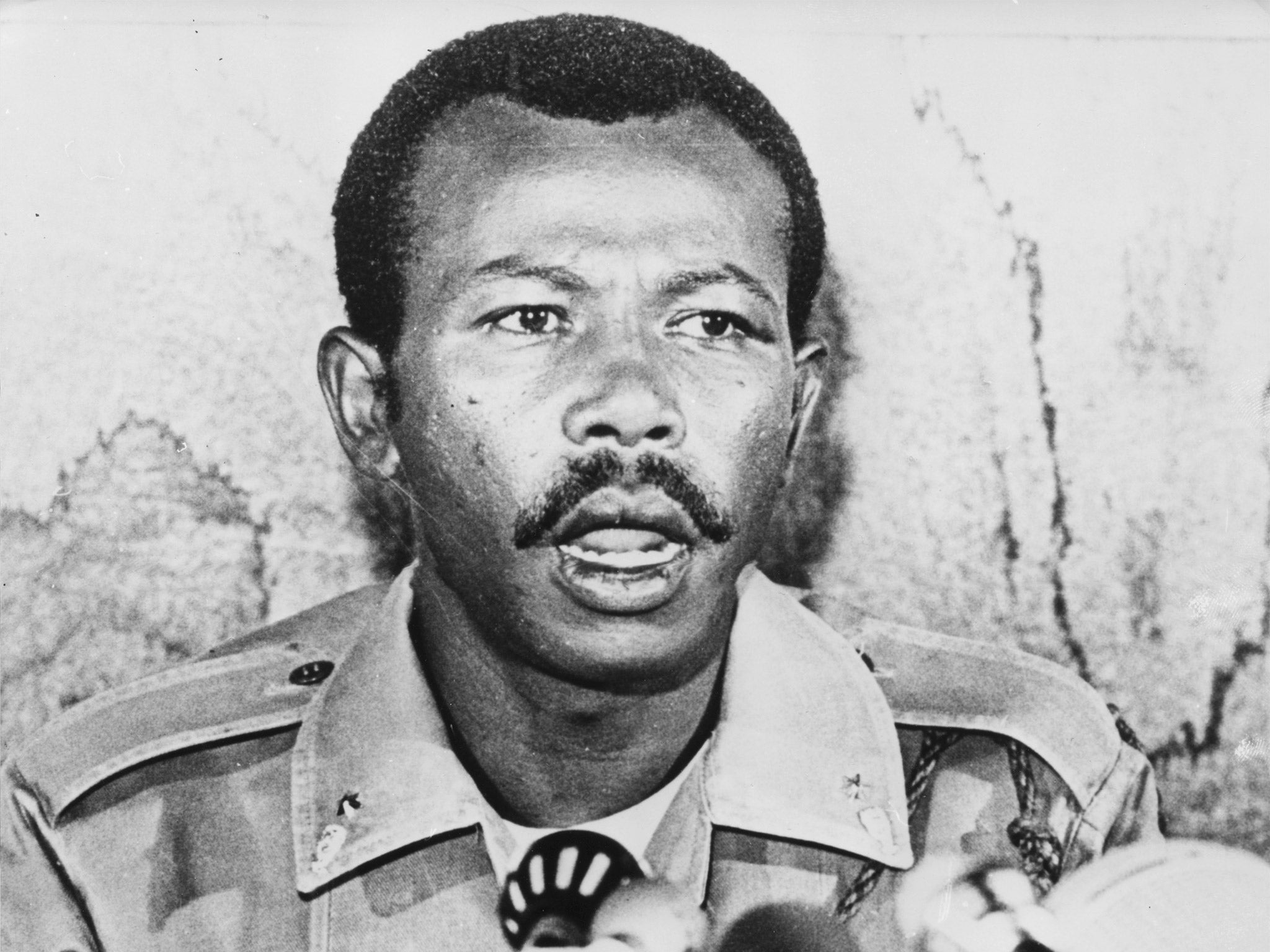

A top secret Downing Street memo reveals how the former Prime Minister wanted to support rebels fighting the authoritarian regime of Mengistu Haile Mariam and suspend some types of relief to the Ethiopians after a year of aid operations to alleviate the famine which killed a million people and inspired Band Aid and the Live Aid concerts.

Documents released by the National Archives at Kew, west London, show Mrs Thatcher decided it was wrong to “jog along” with the Mengistu government, whose human rights abuses greatly exacerbated the death toll from the famine, and lambasted the Foreign Office for failing to come up with robust measures to tackle the regime.

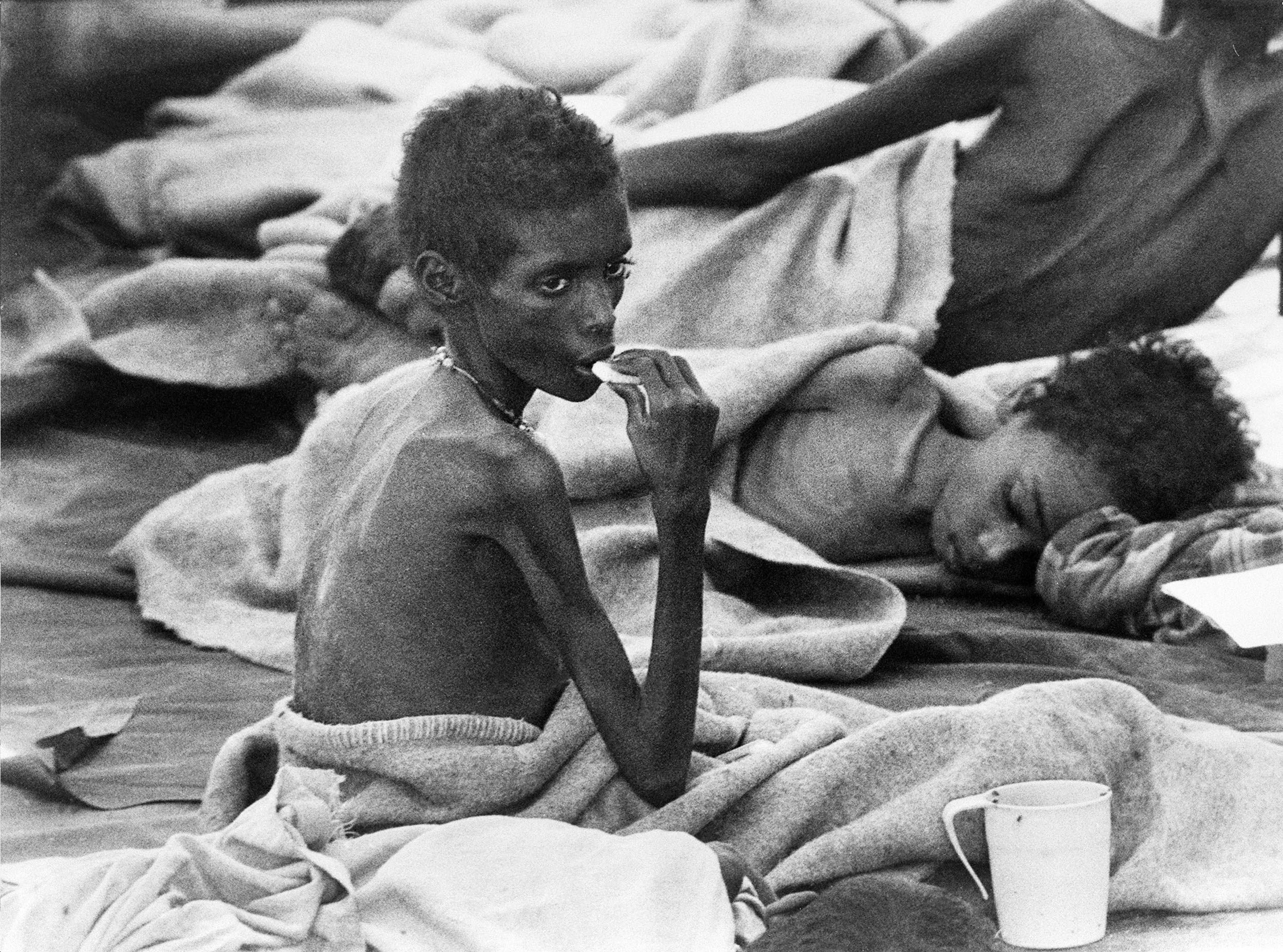

After the existence of the famine across Ethiopia was brought to the world’s notice by the harrowing reports of the BBC’s Michael Buerk in October 1984, a global response was mobilised with at least £150m in public donations and a vast international relief operation delivering hundreds of thousands of tonnes of food. In Britain, the public outcry was led by the singer Bob Geldof, who co-ordinated the Band Aid record and later famously employed the f-word on television to encourage donations during Live Aid in July 1985.

But the secret records reveal profound disquiet at the highest level of the British government as significant aid began to reach the starving and an emergency airlift operation involving the RAF was discontinued towards the end of 1985.

Mrs Thatcher had become frustrated at evidence of problems caused by the Ethiopian regime over distribution of food to famine victims, often in rebel areas, and attempts by the Addis Ababa government to impose customs duties on the aid shipments.

In two memos by her private secretary Charles Powell, it is made clear that the Prime Minister was troubled by the idea that British aid had provided no geo-political influence over Mengistu’s Marxist regime and asked officials to answer the question: “Is it not inherently wrong to pour tens of millions of pounds of aid into a country and yet conclude that we have no serious scope for influencing its particularly cruel and objectionable government?”

The documents, marked “top secret and personal” and restricted to only two copies, asked Foreign Secretary Geoffrey Howe to come up with ways to “put the Ethiopians under pressure and even destabilise them”.

Mr Powell added: “The Prime Minister continues to believes that it is not enough just to jog along in our relations with the distasteful regime in Ethiopia.

“If the conclusion is that our present relations offer no positive scope for exercising beneficial and positive influence, she would like serious thought given to how we can make life harder for the Ethiopian regime.”

Among additional suggestions put forward on Mrs Thatcher’s behalf in the partially redacted memo were seeking American help to assist opposition figures inside Ethiopia and persuading the then European Community to take a tougher line over abuses such as customs duties.

Stung by suggestions that its earlier answers (which included a plan to improve agricultural policies in Ethiopia) had not “adequately answered” Mrs Thatcher’s concerns, the FCO huffily replied that it had succeeded in persuading other European countries to stand up to the abuses of the regime, which was propped up with extensive military support from the Soviet Union.

Senior diplomats poured cold water on suggestions that covert aid to rebels in Eritrea, at the time still a dominion of the government in Addis Ababa, would be a sensible strategy.

The reply, sent on behalf of Mr Howe, said: “It would lead to even greater misdirection of the resources in Ethiopia towards civil war and would thus increase the likelihood of further famine and the need for further large-scale Western humanitarian aid.”

Noting that the famine situation still remained critical, the memo concluded: “The Foreign Secretary shares the Prime Minister’s distaste for pouring aid into a country whose policies are objectionable. Nevertheless he does not see how we can avoid regarding humanitarian considerations as paramount.”

The exchange seems to have produced a stalemate between Mrs Thatcher and her Foreign Secretary. A note on the FCO’s reply by Mr Powell states: “Prime Minister, pretty much a nil return… Agree to leave it at that for the time being?”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments