Why aren’t the Liberal Democrats doing better in the polls?

Resurgent Lib Dems have reasons to be cheerful as they gather for the party conference in Bournemouth, but they need to be tactical, says Sean O’Grady

An oddly worded invitation from the Liberal Democrats arrives on Twitter: “Winter is coming...but this Saturday-Tuesday, let the Lib Dem Autumn Conference cheer you up! 4 days of lively debates, 95+ training sessions, 125+ fringes, 50+ stands...we have concessionary, day, first-timer, weekend, online rates.”

It recalls one of the more charming aspects of the old Liberal Assembly, before the merger with the technocratic SDP in 1988, when any Liberal Party member could just turn up and vote on party policy, no questions asked. A bit too liberal, that – and things are run more like the other two parties now.

At any rate, it’s almost certainly the last conference (we must pray) before the 2024 general election. For the first time in many years, the party has something to look forward to. They’ve been winning lots of by-elections, regaining their traditional strength in local government and are gradually emerging from the wreckage of the Cameron-Clegg coalition and the tuition fees fiasco. It’s been more than a decade, after all.

Does the Liberal Democrat conference matter?

The party’s constitution states that its federal conference determines UK-wide policy, and the federal policy committee “shall have the responsibility for preparing the party’s general election manifesto for the UK … in consultation with the parliamentary party in the House of Commons.” So in the event of a Liberal Democrat government, or cooperative arrangements with other governing parties, the conference does matter. The Conservative-Liberal Democrat coalition agreement for government in 2010 had to be approved by a special party conference.

Why don’t the Lib Dems pledge to rejoin the EU in their manifesto?

Because it didn’t work last time. Jo Swinson – the now-forgotten leader during the 2019 election – sought to scoop the Remain vote and put a stop to Brexit for good. Indeed, she promised that a large enough vote for her party would represent a mandate to stop Brexit, with no new referendum required. As was always obvious, it didn’t work and her hubris got the better of her. She even lost her own seat to the SNP, giving rise to a celebrated clip of Nicola Sturgeon looking as if she’d just taken delivery of a really massive new mobile home.

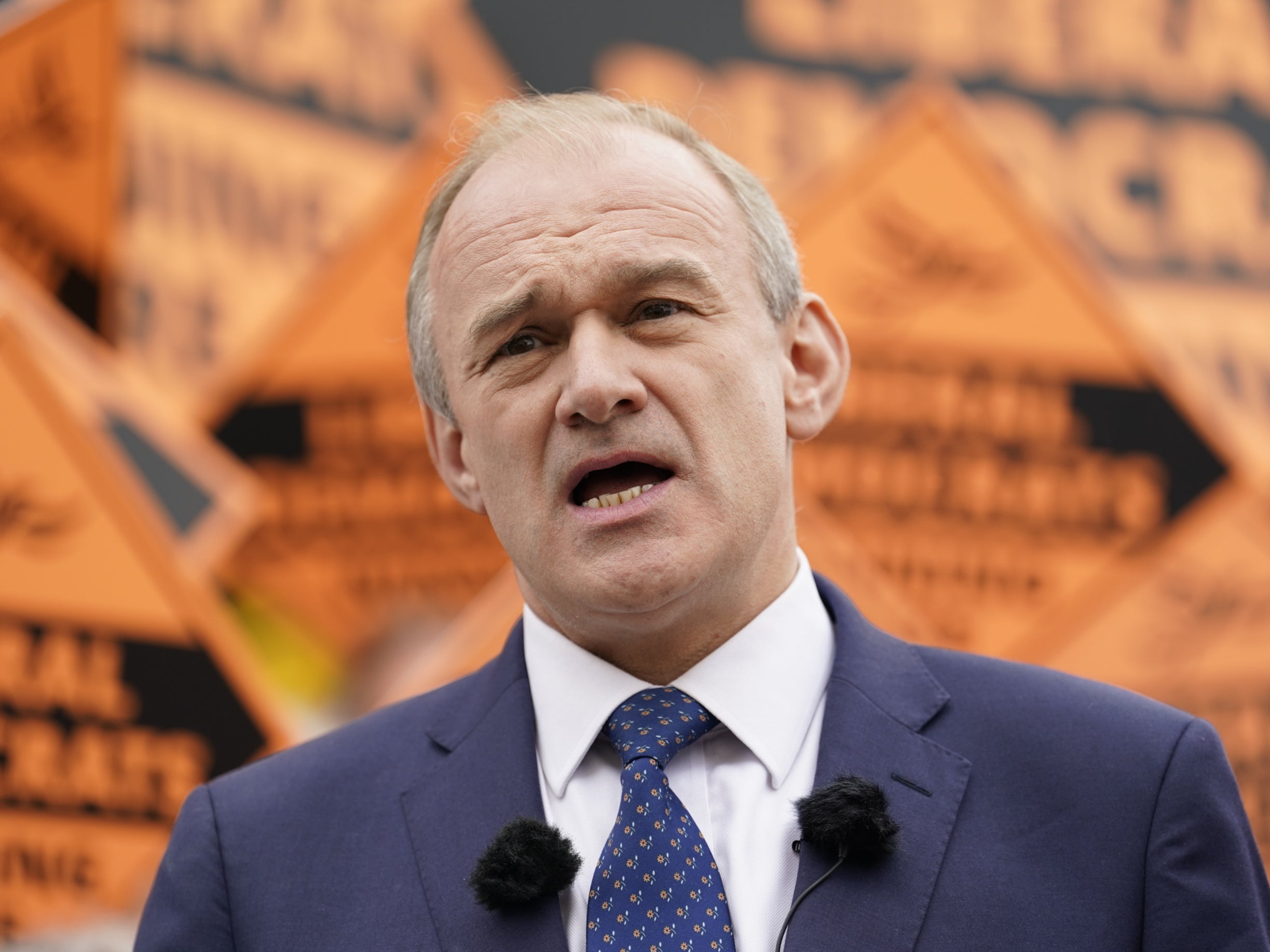

Sir Ed Davey doesn’t want that sort of distraction again: rejoining the EU is “off the table”, he declares. Expect some disappointment from the representatives in Bournemouth.

What will the highlight of the conference be?

Sir Ed’s speech. A much-underestimated politician, he hasn’t had the impact of some of his more telegenic and charismatic predecessors, but they usually had a couple of general elections to make their mark. Next year will be Ed’s first, and the party has been led by different leaders at each of the last three general elections (Swinson in 2019, Tim Farron in 2017 and Nick Clegg in 2015).

Why aren’t the Lib Dems doing better in the polls?

The ideal conditions for a centre party breakthrough are when both main parties are relatively unpopular (as in 1974, 1983 and 2010). Second best is when the Tories are on the floor and Labour is doing relatively well (eg 1964, 1997, 2001). This is obviously the case at the moment, and the 10 per cent the Lib Dems generally score in the polls is on the low side. During a general election campaign, parties get a guaranteed share of airtime in broadcast news, and so the Lib Dems tend to put on a few points. Fifteen per cent might be a realistic target for next time; around the level they enjoyed in the Paddy Ashdown era, with 30 to 50 seats. With that, they would probably overtake the SNP in the Commons, with the coveted third party status giving them a regular slot at PMQs and a few select committees to chair.

It’s also fair to add that the road back from the near-wipeout in 2015 has been slow and arduous. The Greens have nibbled away at the Lib Dems’ appeal as a radical protest vote.

Will they hold the balance of power in the next House of Commons?

It’s quite possible, though at first sight the idea seems far-fetched. The Liberal Democrats have become expert at targeting resources on key constituencies, so that even a national vote of 10 to 15 per cent could yield a surprisingly large number of seats. Almost all their best prospects are held by the Conservatives, for example in the West Country and the home counties, where Labour is weaker. So a pincer movement and active anti-Tory tactical voting – in evidence already – might turbocharge both opposition parties. But it would simply mean the Labour majority over the Tories would be even bigger. In 1997, when private hopes of a centre-left realignment ran high for Ashdown, Tony Blair’s crushing landslide killed any possibility of coalition.

On the other hand, apart from the aberrations of 2019, recent British elections have been indecisive affairs, partly because of the vagaries of the British electoral system. We had hung parliaments in 2010 and 2017, plus one slim Conservative majority in 2015. Whatever else emerges, we may be sure there won’t be another Con-Lib Dem deal. What Sir Ed Davey agrees with Sir Keir Starmer probably won’t be clear until we see the arithmetic of the hung parliament, if there is one.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments