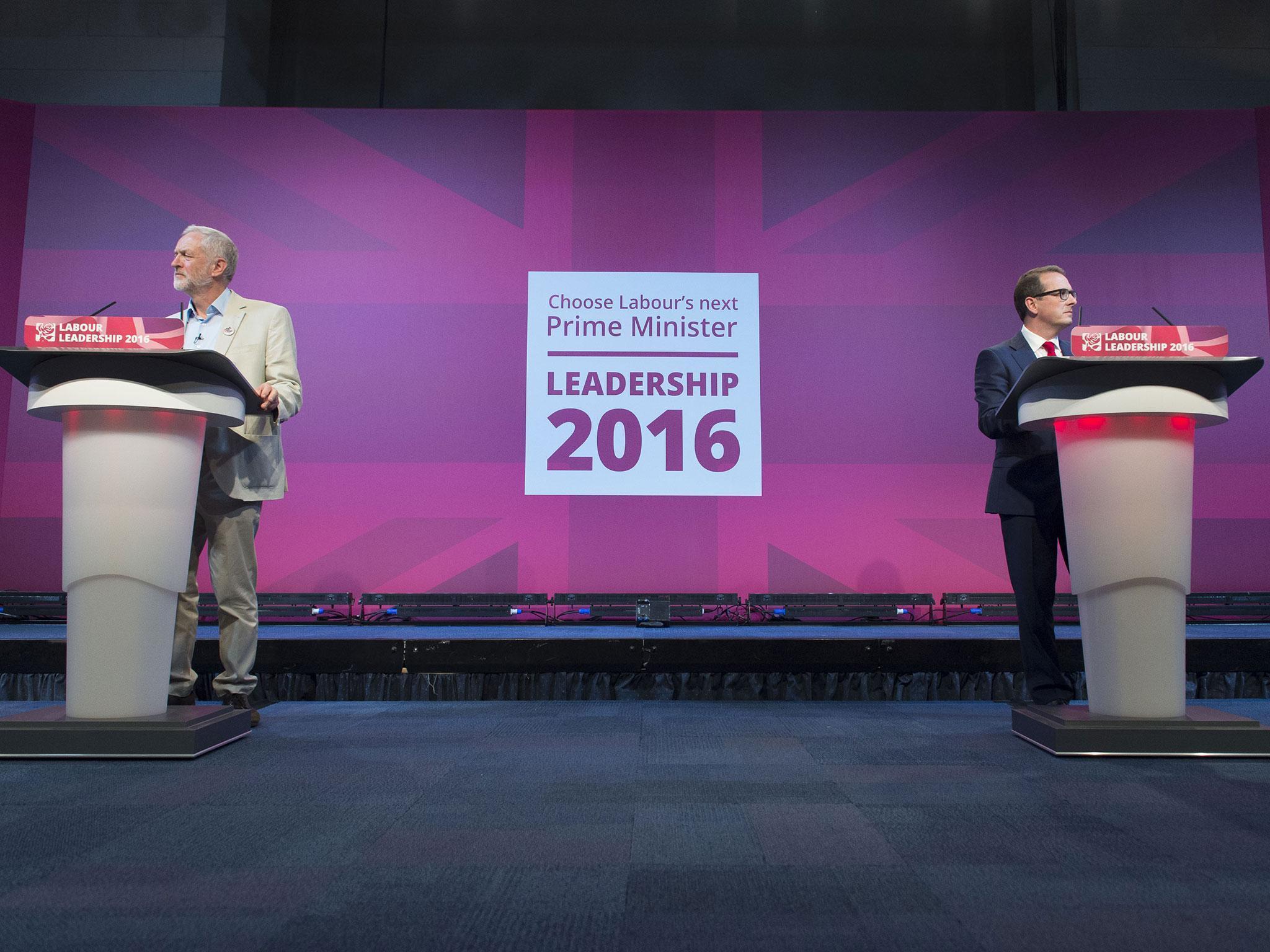

Labour Party leadership row: How did the party get to its worst state in 85 years?

If Labour is to have a realistic chance of winning in 2020, they would likely need to open up and hold a double digit lead over the Conservatives

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The question hanging over the Labour Party is not whether they win the next general election. On current showing, defeat is a given. The question is whether that defeat will be Labour's worst result in a century.

The benchmark is the election of 1931. After an open rift between the party and the Labour Prime Minister, Ramsay Macdonald, Labour scored 29 per cent of the vote in that election, and saw the number of Labour MPs drop from 277 to 52.

It is extraordinary that anyone could even think anything of the sort might happen again, given the huge benefits for Labour of the Corbyn phenomenon. Last year’s leadership contest would have been a mind-crushingly dull affair if the kindness of a few MPs such as Margaret Beckett and Jo Cox had not let Mr Corbyn join the contest.

In May 2015, paid up membership of the Labour Party was around 187,000, the product of 18 years’ decline. By October it was 370,658, as a result of excitement generated by Mr Corbyn's unforeseen rise. Another huge surge after the June referendum, in reaction to the news that Mr Corbyn’s leadership was under threat, brought the total to 515,000, the highest in modern times.

Added to that, the decision to charge non-members £25 each for the privilege of voting in the leadership election added £4m to the party’s bank balance. And during the current leadership contest, Mr Corbyn has been touring the country drawing huge cheering crowds. It is more than 30 years since a Labour leader has attracted rallies of a comparable size.

Yet the spectre of 1931 was raised when Mr Corbyn’s own constituency party, Islington North, met this week to decide whom to endorse in the leadership election. The speaker is not well-known, but he is someone close enough to Mr Corbyn to know what he is talking about. Neale Coleman, a natural Corbynite by political conviction, has been active in the London Labour Party for decades.

In the 1980s, he played a central role in exposing Lady Shirley Porter, the corrupt leader of Westminster Council, said to be Margaret Thatcher’s favourite local politician. Ken Livingstone hired him to work for the London Mayor’s office, where he was so well regarded that Boris Johnson kept him on despite his well known left wing politics.

He gave that up in 2015 to be a political adviser in Mr Corbyn’s office, having backed him in the leadership campaign. But after a few months, he left. When the Islington North party met to nominate Mr Corbyn, Mr Colement pleaded in vain for them to back Owen Smith instead, warning that Mr Corbyn is leading Labour towards an electoral disaster to match the 1931 result.

That warning coincided with two scraps of relatively good news for anyone who would like to see a Labour government again. It emerged that the statistical possibility of Labour winning the 2020 election is better than zero, as a new poll showed the gap between Labour and the Tories narrowing.

The latest YouGov poll puts the Conservatives on 38 per cent and Labour on 31, where last week the same polling company was giving the Tories double digit leads – though on the same day a TNS poll put the Conservatives 13 points ahead.

Labour's seemingly mad exercise in self-destruction arises from a fundamental difference over how change and reform is brought about in a parliamentary democracy

And Electoral Calculus has revisited the calculations which they posted online earlier in the week, which put the statistical probability of Labour of winning the next election outright at zero. That startling finding was a glitch caused by an “outdated parameter”. The corrected figure is that Labour has a nine per cent chance of outright victory, compared with the Conservatives' 63 per cent chance.

Past experience is that opinion polls overstate Labour’s support and underestimate the Conservatives'. There is also a general tendency for governments to trail in the polls mid-term, and to close the gap on the opposition as the election approaches. This suggests that if Labour is to have a realistic chance of winning in 2020, they would need to open up and hold on to something like a double digit lead over the Conservatives. Instead, a government which perpetrated one of the worst political blunders of recent times by calling a referendum they expected to win, and losing it, can apparently look forward to many years in power while the main opposition rips itself to pieces.

Labour's seemingly mad exercise in self-destruction arises from a fundamental difference over how change and reform is brought about in a parliamentary democracy. Hilary Benn and the 60 other who resigned from Mr Corbyn’s front bench, and others who declined to serve under him at all, believe that it is achieved through Parliament, by winning a general election, and using the established levers of government. In their eyes, Mr Corbyn is hopeless as a leader of a parliamentary party.

But Mr Corbyn, John McDonnell and their allies believe that the main motor for change is by mass action. They see those rallies and street protests which are Mr Corbyn’s favourite milieu as a wake up call to a supine parliamentary party, full of people whom Mr McDonnell once described as “f***ing useless.” For the young coming into politics for the first time, and others who feel that the parliamentary system has done nothing for them, the Corbyn strategy offers so much more hope and excitement.

How much of that will survive the reality of a general election remains to be seen.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments