Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

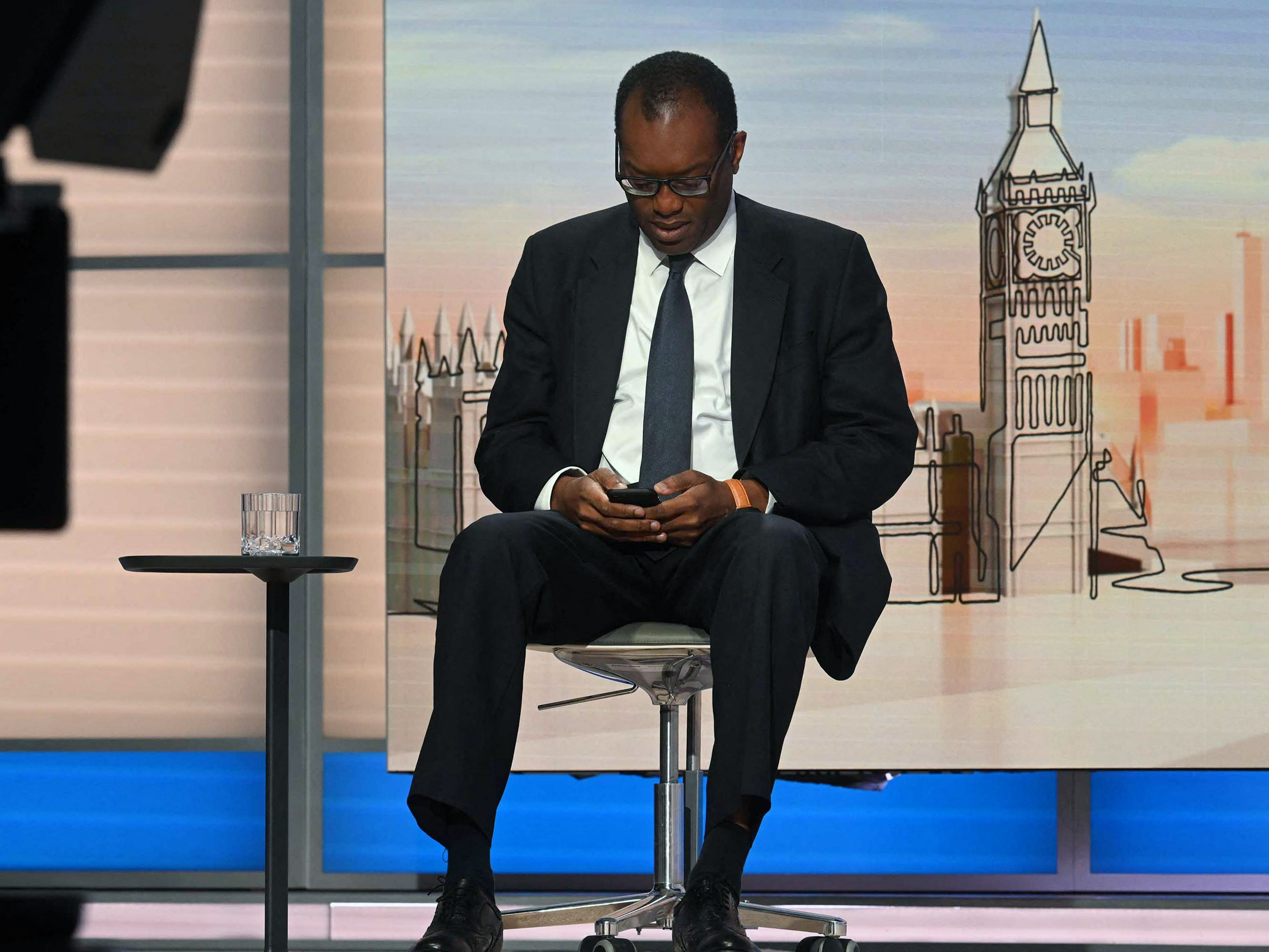

Your support makes all the difference.The fallout from chancellor Kwasi Kwarteng's mini-budget has been overwhelmingly negative.

The government's economic policy has been described as a "doomsday cult" by the chief economist of UBS, the world's largest wealth manager.

And former US Treasury secretary Larry Summers says Britain "will be remembered for having pursued the worst macroeconomic policies of any major country in a long time".

But what exactly has the government done and what is the problem?

Unfunded tax cuts

The most significant policy change the government made in the budget was to roll out a series of unfunded tax cuts.

Sometimes governments cut taxes because they have more money coming in than they expected, so they pass on savings. This is not that. Sometimes they make cuts to spending and reduce taxes to match. This is not that either. The government has moved to significantly reduce its revenue without reducing its costs.

The commitments are huge: Scrapping the top rate of tax for the highest earners will cost £2 billion every year by 2026. Cuts to stamp duty will cost £1.7 billion a year. The cut in the planned rate of corporation tax will leave a £18.7 billion hole in the budget, while reversing the 1.25 per cent rise in National Insurance will cost £18.1 billion.

The government claims these cuts will boost growth by leaving people with more money to spend. This remains to be seen: but the financial markets are not confident in the government's approach.

So what did the announcement do?

There have been two immediate effects from the government's policy, both related to the financial markets.

The first is that the pound has tanked in value relative to other currencies. More on that in a second. The second is that the cost of government borrowing has massively increased. We'll also elaborate on this.

There is also a third expected outcome, which is that the Bank of England is now expected to raise interest rates dramatically – increasing borrowing costs for households and the private sector. This is very significant, and we’ll unpack it at the end.

Tanking the value of the Pound

The most high-profile of the changes prompted by the Budget has been the Pound sinking to record lows on the currency markets. On Monday Sterling tanked to its lowest ever level against the dollar, and it is also significantly down against the Euro.

Currencies tank in value when markets lose confidence in a country’seconomic management and the value of its assets. As a result of this falling confidence, market demand for Pounds falls, so its value falls relative to other currencies. Each pound is worth less.

Financial markets go up and down all the time, and some of the fall was recouped during trading on Monday – before the Pound fell again. But a record low is a clear direction of travel, and many analysts expect Sterling to go even lower.

Nick Macpherson, former Treasury permanent secretary said on Monday that "market pressures will play themselves out over weeks and months". "There will be rallies followed by brief substantive lurches downwards. We probably haven't seen the bottom," he added.

The main effects of this change is that it will now be more expensive to buy things abroad, and cheaper for foreigners to buy British things.

Unfortunately, the UK imports significantly more than it exports and many things may become even more expensive for consumers – whether household goods, imported energy, electronics, or food.

In 2022, supply chains are global, and even goods that are produced domestically may require inputs sourced from abroad. These price increases will hit despite inflation already running at a 40-year high. The cost-of-living crisis may yet get worse.

Surging government borrowing costs

The other market movement prompted by the government's policies has been a significant increase in borrowing costs for the government.

The British state borrows money to fund spending by selling bonds or "gilts" to investors, who get an interest rate in return for buying and holding them.

Since the global financial crisis, these interest rates, or "yields" have been at rock bottom. Sometimes investors even paid the Treasury to take money off their hands, with negative interests rates. But all that has now changed.

Yields on 10-year bonds have now risen above 4 per cent, the highest figure since the 2008 financial crisis. This is more than triple the 1.3 per cent rate the government was paying at the start of the year.

As with the currency exchange markets, this reflects a loss of confidence in UK economic management and prospects. Investors now see the UK economic as a riskier proposition, so are not willing to lend the government money as such low rates at auction.

This is particularly inconvenient for the governemnt, because they have just announced billions in unfunded tax cuts – which will require a lot of borrowing.

The rise in borrowing costs also makes plans for state investment to deliver growth harder – committed projects like Northern Powerhouse Rail will be more difficult to fund and may be at risk politically. And it will put pressure on the Treasury to rein in spending in other areas, so could lead to more public sector austerity or further tax rises down the line.

What about interest rates for mortgages?

The base interest rate is set by the Bank of England. Like government borrowing costs, the base rate has been close to zero since the 2008 financial crisis – though it has increased a little to 2.25 per cent over the last year.

But in the wake of the budget the Bank is now expected to move to increase rates even more dramatically.

While markets do not set the rate, they can be used to predict it – and investors now expect the Bank to triple interest rates to 6 per cent by next year.

The Bank raises rates because its mandate, set by the governemnt, is to keep inflation at 2 per cent – and inflation is currently at 10 per cent. So the Bank moves to bring inflation down.

Higher interest rates mean fewer people can afford to borrow money, which means fewer loans are issued. Fewer loans means less money in the economy, and less demand for goods and services, which means price rises are controlled.

But this process hurts. 6 per cent interest rates will mean anyone on a variable or tracker mortgage will see a significant increase in monthly payments – as will anyone whose fixed mortgage is coming up for renewal.

This will likely to lead to defaults and people having to hand back their keys. For others, it will mean significant belt-tightening. First time-buyers will also struggle to get a mortgage.

Elsewhere in the private sector, businesses will also find it more difficult to access loans to invest or get trading with.

All these changes may have significant knock-on effects. If demand for housing dries up, house prices may crash, as they did in 2008. If monthly bills rocket, demand could be taken out of the economy and businesses may get less custom – causing a recession and job losses.

In summary

The government is hopeful that its tax cuts will leave people with a bit more cash to spend, and boost economic growth.

However, there is a real danger that the damaging knock-on effects of these cuts will end up significantly eclipsing any potential gains.

Some richer people may gain enough for tax cuts to have more money to spend. Almost two thirds of the personal tax cuts in Friday’s budget go to the richest fifth of households, according to the Resolution Foundation think-tank.

But others will gain very little, and will be hit by higher inflation and mortgage payments at just the same time their energy bill is already going through the roof.

Whatever happens, the markets certainly seem to be worried about the's UK economic prospects.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments