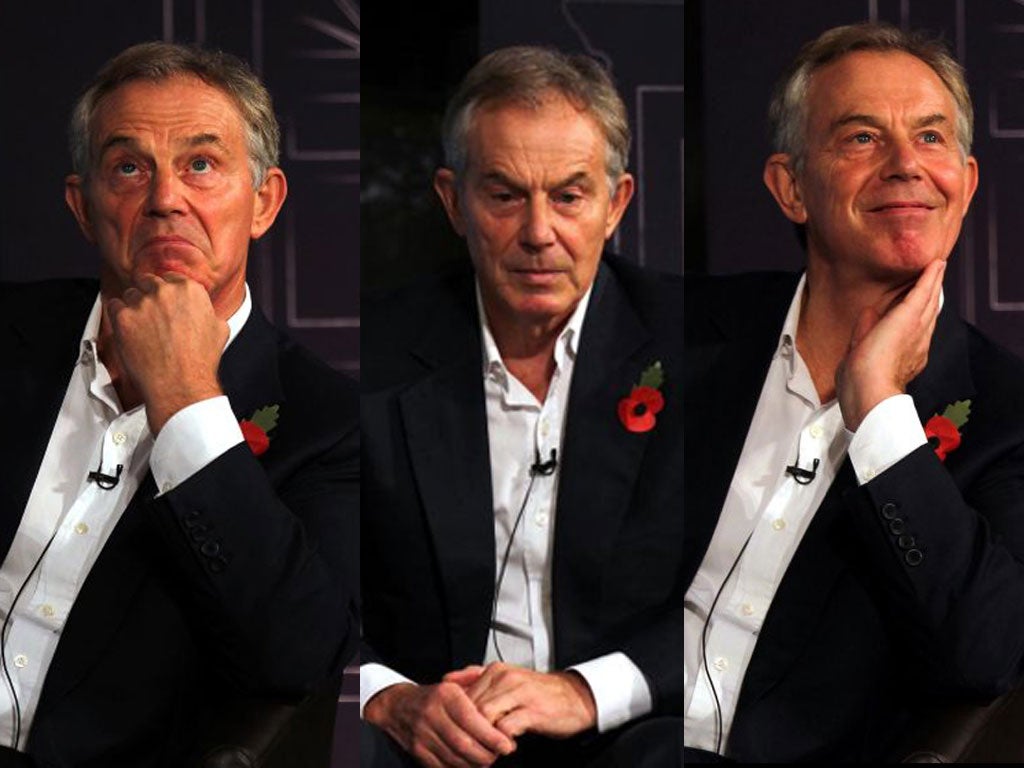

In full: transcript of Q&A with Tony Blair at Mile End Group, London

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Transcript of Q&A with former Prime Minister Tony Blair at the Mile End Group, London

DR JON DAVIS

Good morning and welcome to the 100th Mile End Group. Thank you so much for you all for braving the wilds, all I can say is this the luck that the East End gets. This is how bad it is but actually it's also indicative of the fact that nothing stops us. Queen Mary is absolutely known for that. I'd like to say a very big thank you to our sponsors Hewlett Packard, who in the words of Lord Hennessy are the Medici of commercial friends. I'd also like to say a big thank you to the Corporation of London.

I've been at every one of these Mile End Groups, we've had some wonderful speakers and several of them I'm very pleased to say are in the audience today. They've been educational, they've been entertaining, they've attracted a very eclectic audience, but I must say I don't think any of them have been quite as good as that first one. There was about seven people - as you can see on your list - there was about seven people; it was beautiful, all about Edward Heath's machinery of government reforms, and I really think that with those seven people and the dog it never quite reached that high point. I'm hoping, Tony, that you will be able to surpass it. I gave it; there we go.

I'd like without further ado to hand over to my great friend Professor John Rentoul who will chair the meeting.

JOHN RENTOUL

Thank you. Thank you very much Jon, and thank you Tony Blair for coming to the 100th meeting of the Mile End Group, which has been one of the jewels in the academic crown of Queen Mary, and many, many of its regular attendees are here today: civil servants, academics, students and maybe even one or two feral beasts, I'm not quite sure - I think there's maybe a journalist or two in the audience - along with students from the course that Jon and I have been teaching. Virtually since you stepped down as Prime Minister we've been teaching the Blair Government course, and then the New Labour in Government course here. And two years ago some of the students came to your office in London to have what must have been the most unusual seminar with their subject, their actual subject, in the room, talking about democracy and how government works, as opposed to how academics, including academics at Queen Mary, think it works.

The reason we're here is because one of the things you said then was that people sometimes think that the power of Parliament has declined, when what they mean is government is doing things they don't like. You said that complaints about Parliament, and about the way government works, were possibly less important than the declining pool of ministerial talent. You mentioned having to bring in Andrew Adonis in through the House of Lords, and then you said, "I think there's a big debate about democracy, and one of the things I'd like to do is initiate and take part in that, about how you mature your democracy in the modern age, which I think is a far bigger and more interesting topic than what some constitutional experts are obsessed by, which is, 'Why isn't the world of 2011 like the world of 1961?'"

So, that's our subject for this morning. I'll just ask you a couple of questions to start us off. I saw that you were in Romania the other day, where the Prime Minister, Victor Ponta, said, "We only discussed one matter, namely the setting up of a new government entity to be in charge of such projects that the government considers as priorities, following a pattern used in the UK during Tony Blair's term in office." I assume he's referring to the Prime Minister's Delivery Unit. If you would be able to tell us more about the advice you give to governments like the government of Romania that would be fascinating.

Jack Straw, who I don't think has made it through the - through the weather today, wrote a - a memoir that wasn't as good as yours, but, you know, it's quite good -

TONY BLAIR

Jack's not here, is he not?

JOHN RENTOUL

It's - it's all right. It's completely safe. He's not here - in that he said that he thought that the Prime Minister had too much power in the British constitutional system, and I was hoping you would respond to that. But, the floor's all yours, and then we'll take questions from the audience.

TONY BLAIR

Right, well first of all thank you very much for having me here, especially with such a distinguished audience, and thank you to the two Johns for the course.

So, just by way of opening, I mean, I learnt a lot in government, and I've learnt a lot since leaving government. The kind of, journey of being in government is that you - you start at your most popular and least capable, and you end at your most capable and least popular. And that, sort of, transition is really all about the education: about what government today is about. And since leaving office - I mean, by the end of this year there will probably be like 20 different governments in different parts of the world that myself and my - my team will cooperate with. And, really, what most political leaders, and I can only talk about this from the position of the political leader - the challenge they face today is not so much, as it one in times passed, one of ideology, not so much to do with issues of honesty or transparency, although that is an issue in many countries, and the media tends to focus on that, the challenge is the challenge of efficacy: how do you get things done? And the reason that that is very important is because of what government is called upon to do today, which, I think, is qualitatively different from what it was asked to do in years gone by.

And since Robin [Butler, Cabinet Secretary to 1998] is here, and forgive me if I but on my very first day in office, when what happens in our system is that you have no transition, you just win the election and go straight in there. And what happens is that the tradition is that the civil servants all line up on either side of the - the room going down the Cabinet Room, at the end of the corridor in Downing Street is the Cabinet Room. And what happens is that the tradition is the outgoing Prime Minister goes down the line, and everyone says goodbye, and then a new guy comes in and everyone says hello, right? So, they, sort of, applaud the new person in. Well, we'd been out of power for 18 years, so I came in and I was going down the line and lots of people were crying. So, you know, you got to the end of the line and suddenly feel guilty about the whole thing. And then I came into the Cabinet Room, and I remember sitting there: there was just - the only person in the room was Robin Butler, who was the head of the civil service at the time. And I remember he just motioned me into the chair opposite him, and saying to me, you know, 'Well done.' And then he said, "Now what?" And the "now what?" is the single most difficult thing that you have to - to then answer, and the "now what?" is a lot harder today because of the fact that you are changing legacy systems that have grown up around the public sector over many, many years. And that is hard: really hard. And it requires, in my view, a quite different skill set from what's gone before.

I mean, a lot of Margaret Thatcher's reforms were about passing legislation, which was politically very, very difficult. But - and some of it obviously involved systemic change, but a lot of it involved - the passing of the legislation was the - the important act. But when you look at things like welfare reform, healthcare reform - which is a big issue here and everywhere - education reform, law and order, criminal justice, you're talking about systemic changes in legacy systems that are grown up over a long period of time, and that it was is tough. And what it requires is a) a far better quality of policy advice, and by the way there's a huge market in ideas out there that often doesn't touch the world of politics. So, you need to be searching for those ideas in different places. Secondly, it requires a different skill set within the civil service. The civil service, actually, has made a lot of changes over the past few years, but it is absolutely necessary it does so. Thirdly, performance management. You know, skills often associated more with the private sector become absolutely central to delivering these systemic changes. And the changes often need to be long term, whereas politics works short term, and they often need to try and achieve a consensus, whereas politics has become more and more partisan.

So, this is what political leaders face today. And it isn't a question of whether, you know, the civil servants - service is good or bad, it's that the world has changed so fast, and is changing so fast, that if you don't change the way that you govern you - you just become somewhat redundant and irrelevant. And, in my view, the root of cynicism about politics is a lot less to do with a lot of the issues people often talk about; it's to do with the fact that you've got an electorate today that's far more assertive about their own individual circumstances, and yet they still think that government works in a very old fashioned way.

So that's the nature of the challenge, and that's what I found, and that's what I think is fascinating to work on. But round the world today, the reason why what we talked about in government finds such an echo, is that all these governments have exactly the same problem.

And so the moment I'm talking to another leader in the world today, you know, they - it's like a light switching on the moment you talk about this, because they know that's their problem. And so, if you're in a poor African country, or an emerging market country in the Far East, you know you've got to get the electricity switched on, you've got to get roads built, you've got to get your basic reforms done around things like agriculture, and doing business. You know, issues like the rule of law matter dramatically today - more than ever mattered before - but you've got to put those reforms in place. Getting the quality advice and implementing is what it's all about.

JOHN RENTOUL

So, you don't talk to these governments about collective cabinet responsibility, neutrality of the civil service, and all the things that we teach in - I mean, we've got a course here called Cabinet and Premiership, where we teach - we teach all about those subjects: about the neutral civil service, the traditions of Northcote-Trevelyan, and all the rest of it. You think we should be teaching something completely different?

TONY BLAIR

Well, I think those things are important - I'm not saying they're not important. I'm just saying they don't answer a lot of questions that, if you're a political leader today you're asking. So, you know, you've just got to be frank about that. And the crisis of democracy, in my view, is not a crisis around honesty. Not in our system. That's not the problem.

You know, it's what people focus on. So if something like MPs' expenses occurs, and you get this huge wave of, you know, dissatisfaction and - you know, perfectly understandably. But it's not the problem. The problem is how do you attract sufficient talent and quality around ideas, around strategy, around delivery. And if you can't do that, you can't make government work. And that's what frustrates people, because then the gap between what they, today, expect and what you're able to deliver becomes, you know, just a huge gulf.

JOHN RENTOUL

And in one of your final speeches before you stood down, you had a go at the media. How much responsibility do you think the media play in this - journalists play in this? And what is your attitude to press regulation?

TONY BLAIR

Look, I mean, I think now with the - social media is just a fact of life. I'm pretty sceptical that anything much can be done about it. But I do think it requires a quite different response from politicians today. I mean, I think dealing with social media - I mean, the media world has dramatically changed even in the years that I've left office.

JOHN RENTOUL

Are you on Twitter?

TONY BLAIR

My office is on Twitter. I don't tweet myself - at least, not intentionally, but it's - no, I mean - but I probably should do, I should think. Yeah. I mean, it's just - it's - one of the most difficult things today in politics is there's such noise generated around you and around your decision making, I think it's really hard for a political leader to take a step back and work out what is real and what isn't. You know I sometimes get political leaders who'll say to me, you know, "You want to see what's happening on Twitter around such-and-such." And I say to them, you know, "That may be real, and it may be representative, or it may not. Or it may be a spasmodic burst of opinion rather than a considered strand of opinion." You've got to - you know, dealing with that, I think, is very tough. The other thing I think's really interesting, when I look back on my time - and I say this to leaders a lot - is that as a result of the way the media works today, scandals and crises, that is just part of your life. So you're living with a constant, as I say, barrage of noise and static around you.

The interesting thing is when you finish your time and you look back and say, "Well, what did I do and what did I achieve?" a lot of that really falls away, and what's left is the residue of things that are actually important. So I think keeping your mind focused in that way is very hard today, but more necessary than ever.

JOHN RENTOUL

That's a very striking point when you read back through a lot of Alastair Campbell's diaries which are all about media firestorms that seemed terribly important at the time but people can barely remember now.

TONY BLAIR

Yeah, and I think, by the way, one of the things is, when you look at this through the prism of the media and, you know, you look back on the time, it looks as if, you know, government's always reacting to media events whereas actually there's a whole set of things in government that are, you know, just, you should get on with, in respect to the scandals that's happening.

But to be able to keep your mind - you know, if something is revolving around - especially something that touches on your integrity or people you know, or, you know, it's a scandal about a minister that you've got to deal with, to keep your mind on public service reform while that is going on around you is very tough to do, you know? But you've got to do it because at the end - as I say, I can't even remember half the scandal that I was - probably just as well.

JOHN RENTOUL

Right, I'm going to open it up but I just want to ask one more question. My esteemed colleague Steve Richards said there was no such thing as a Blairite in a column the other day, which I disagreed with. But I found it rather difficult to formulate a definition of what a Blairite was except somebody called Alex Doel sent me a message on Twitter to say that a Blairite is an individual who stubbornly refuses to make the Labour Party unelectable. I wondered what you thought of that definition.

TONY BLAIR

Yeah, I told you Twitter was good. No, I think it's a lot more than that, actually. I mean, look, it's not particularly connected with me, it's - there is a modern, progressive political strain that is saying, essentially, our essential values around social justice and the creation of a more just society where opportunity is given to people irrespective of their background or wealth - that remains our core objective, but the means of achieving it has got to change in a revolutionary way because the world around us has changed. So globalisation, technology, demography means these things have got to be delivered in different ways. So the academy programme is a programme born out of the fact that bad schools do not deliver social justice. And if bad schools are delivering a bad education for the pupil, at some point you've got to understand whether this is a systemic change that's necessary, and make it. That's what it's about. It's about modern, progressive politics.

Now, I happen to think it's the politics that makes you electable, but the reason for that is - you know, politicians sometimes talk about electability as if, you know, it's just a matter of conning the public. Actually, it's a matter of persuading the public and in my experience, usually, the public gets it right.

JOHN RENTOUL

Thank you very much. Now, who would like to ask questions? Can we have short questions? You can make them as hard as you like, because I don't think there's been a question that's actually thrown TB in the past 10 years.

TONY BLAIR

Always a first time.

JOHN RENTOUL

But if you could say who you are - I know who you are. Lord Butler, you can go first.

QUESTION

Thank you very much. Tony, first of, I preface this by saying I agree with everything you've said so far. But since you referred to those first few moments when you came into the Cabinet Room, I just want to elaborate on that, because - and here, I'm not relying on my memory but on your book - because the next thing that happened was, I said to you, "We've studied your manifesto, and we're ready to help you implement it." And you then say, "I found this remark strangely disturbing."

TONY BLAIR

Absolutely.

QUESTION

Could you tell us why?

TONY BLAIR

Yeah, I can, actually, and it is a reflection on the fact that, when you're suddenly faced with the responsibility to govern, you - at that moment, and through that statement you made, I suddenly realised that the skillset that had brought me to power - because, my point is, not just the skillset of civil servants has got to change but of politicians as well.

You come to power as the great persuader. Right? You get into power, you've got to become a great chief executive. And in the end it didn't matter how persuasive you are - I mean, I remember about 18 months into government and the health service stuff was stalling, and someone said to me, you should go out and make another speech about it. And I went absolutely nuts and said, "I've done enough speaking about it; I actually need to study it in detail and work out what is the right way, systemically, of changing this system." And actually, out of all of that came the 2000 White Paper that Alan Milburn did.

But that's what I meant, in other words. And one of the - I always, sort of, say sometimes about some of the things that we - I think I said this particularly about the Freedom of Information Act, which is another topic altogether, when I thought, you know, where was Sir Humphrey when you needed him? In order to tell you what a profoundly bad idea that was. And, you know, when you suddenly said that to me, I thought, yes, that's all very constitutionally proper, but let me now just reanalyse my manifesto, not in terms of its persuasive capability but in terms of what it actually can do for people.

So, you know, I think nowadays the best thing for oppositions is to have a clear strategic sense of priorities and a clear - what I would say - compass - intellectual compass - but not to try - not to tie themselves down too firmly to each specific. Because once you get in there, you find things are never quite as you think. But that was the reason for that.

JOHN RENTOUL

George. George Jones.

QUESTION

George Jones, LSE. How do you respond to the charge that your approach to government and what you're recommending now to leaders is far too centralised - a tendency to see all public services as the responsibility of Westminster and Whitehall? And you want to cover through you centralised institutions, strategy, all the way through to implementation. Isn't it all too unmanageable? You can't really grasp all the different factors and the way they interlock. Isn't the real answer to government in the modern age to decentralise to local government?

TONY BLAIR

Right, well that's a very good question. Here's what I think about it because I also talk to leaders who come to power with decentralisation being their central pledge and my attitude to this is as follows. I don't actually think the centre can do everything but I do think in terms of the absolute priorities of government, if you don't have a strong centre it's hard to make the system work in the way you want it to work. And, you know, after all you're elected as Prime Minister to deliver certain things and what we use the delivery unit for was specific priorities, right, so not everything.

And I don't suggest that the centre can replace the rest of government, but I do think two things. First of all, if you don't have a strong centre and you want to change things then you will find that the system manages the status quo, it doesn't actually change the status quo. And, you know, I found in government - well just take the major reforms - some of which have stood the test of time around, you know, schools - actually to an extent - universities, healthcare, even some of the law and order changes and reforms. I don't think any of those would have happened if we hadn't been pushing and driving it from the centre. And, you know, particularly with education by the way, I think that if we'd simply just devolved that and said okay that's up to the locality to do, I don't think we would have got the reforms through. I just don't think it would have happened. I think the system would have just said well look we'll deal with your general statements in our own way and their own way would have meant nothing much happened.

And the second thing though, is that I do think - which is why I supported the development of the mayoral system, you know we introduced the mayor for London. I mean people forget this now, we actually introduced the Mayor for London, I personally believe strongly in local mayors in big cities and so on. I do think there's a point in devolution and decentralisation of power, provided that there's a genuine political accountability at that local level, and one of the reasons I always supported the mayoral system is that I thought it would create a local accountability that was strong enough so that people really competed on the basis of who had the best ideas for the locality whereas what I can see with a lot of local government was that it just depended how the central government was doing as to what happened. Now breaking that link was to be very, very important.

So my view is I agree the centre can't do everything, but my experience was that unless you have a strong centre with a clear political will being forced and pushed down then if you were reforming government you won't get a lot done, but that's, you know, it's a continuing debate let's say.

JOHN RENTOUL

Alun Evans.

QUESTION

Thank you. Alun Evans, once at Number 10 now head of the Scotland office leading the UK government's work against Scottish independence. And I wonder, Tony, if I could ask you - in your role of advisor to government - ask you about how best the UK government should take on the challenge of Alex Salmond and his campaign for independence, leader with a majority, is quite popular up in government, is UK government doing enough, what more should we be doing?

TONY BLAIR

Look in the end, devolution was something that was introduced after 100 years of trying. And, by the way, I'm not sure we could've introduced it if we hadn't acted very quickly on coming in to office. Because the other thing is when you've - something I often say to leaders - when you first come in to office, although you are in one sense at your least capable because of your lack of experience you should use the political capital that you've got to make major change if you want to do, particularly around things like constitutions.

And, so we introduced devolution because we felt that it's a way of making sense of the modern world, which is for Scotland: have a strong sense of identity, but at the same time to still operate within the framework of the UK. And I think the best argument - and it is the argument I think people are making - the best argument is that in the 21st century, especially in a world that is changing so fast, both in Europe and in the outside world where you've got a country the size of China that is going to be the dominant power of the 21st century, then frankly it makes sense for us as a UK to stick together because we're more powerful together, economically and politically. And, you know, to reference another debate that's going on, it makes sense for us to remain in Europe because without that weight we will lose influence and lose power both economically and politically.

And I still think that is the best. I think the best arguments are economic and practical and, you know, by and large I think those are the arguments that are being made. The difficulty always with referendums is they can turn into something that is a decision about, you know, something immediate when in this case and in other cases we will be taking decisions for, you know, the very long term.

So - however, I personally think people have the sufficient sense of the importance of the decision and the weight of it that I hope and believe they'll take it in the right way. But, you know, I don't - I think the way the campaign's being run seems to me to be along the right lines and, I hope, relatively successful.

JOHN RENTOUL

You've promised a lot of referendums but didn't actually hold many, if I remember which is quite -

TONY BLAIR

Well I promised -

JOHN RENTOUL

- probably the right way around. Sorry, let's have a question from -

TONY BLAIR

So what's it - just to explain but one of the things that we did promise was a referendum on the European Constitution, which we didn't have, but that was because the constitution wasn't going to happen. And I always felt it was a slightly odd thing to have a referendum on something that wasn't going to occur.

JOHN RENTOUL

Quite. Let's have a question from a student. Jon Boulton?

QUESTION

Hi there, Jon Boulton formerly of the Mile End Group. Jonathan Freedland wrote in the Guardian a couple of days ago that Gordon Brown should apologise for the mistakes that were made under his government for the sake of Ed Miliband and for the sake of your and his government's legacy, do you agree?

TONY BLAIR

And what mistakes was he referring to particularly?

QUESTION

I think he was referring to mistakes made both by the annual government's overspending - allowing the Tory narrative of overspending to take place.

TONY BLAIR

I mean, I think, you know… First of all, by the way, when I left power in 2007 - and I'll qualify this in a moment - but debt to GDP ratios were significantly down and we'd been repaying debt for the first time in years and years and years. So there's a lot of mythology about certainly those 10 years in office and the issues to do with debt.

It is true and there was a debate about it at the time in government around 2005 -probably we really should have tightened policy somewhat - but these things are marginal compared with the overwhelming impact of the global financial crisis. And, you know, I think for the Labour Party to accept that, as it were, the crisis was created in Downing Street, it would be bizarre. It's a crisis that's occurred literally all over the Western world, all governments have faced enormous challenges as a result of the massive drop in growth. And one of the first things that you learn about government is that the issues to do with debt are hugely impacted by issues to do with growth. So if your growth falls, you're in a situation where - and especially if it falls, plummets in the way that it did after the financial crisis in 2009 - whatever government is in power is going to have a major problem.

So, yes, I mean I think we can say around - you know I think the honest truth is - around the 2005 time, we - and this was a debate that was had in government at the time - this thing called the fundamental savings review that didn't really go anywhere but I think should have led to us then driving through even greater change in the existing amount of money.

But it's - that pales into insignificance compared with the impact of the financial crisis, frankly. And that is the reality, and I think that's what Labour should be saying. And the issue today, the challenge for any government is how do you produce growth in jobs and, in my view, I would subordinate everything to that. So I don't agree with all the decisions that were taken after the financial crisis, I think the recapitalisation of the banks was completely right but I would have probably taken different decisions in other aspects of economic policy.

JOHN RENTOUL

Such as?

TONY BLAIR

I - around national insurance; I would not have been in favour of doing that and some of the other - I mean, you know, some of the issues to do with - even with financial regulation actually, but… However, the fact is any government that would have been in power with a global financial crisis would have had a big problem on their hands.

And, by the way, one thing I always reflect on is in my 10 years in office, I don't think I really was ever met with an opposition that was telling me to spend less.

JOHN RENTOUL

Jon Davis.

QUESTION

Thank you. Mr Blair. Many senior civil servants have spoken to us that you were more respectful and used Cabinet government much more towards the end of your time in government than at the beginning because you started to recognise its power. What do you think about that?

TONY BLAIR

I think that is true in the sense that, you know, when we first came in and this - this was a feature, I think, for the first 18 months or so. You know, one of the things you've got to - as I say, you've got to get over is the fact that you're no longer campaigning, and if you're not careful that, sort of, psychology remains with you when you come into government.

So you're constantly thinking it's about the next thing that you're launching because then opposition… Look, the difference between opposition and government is very simple. In opposition you wake up every morning and ask, 'What do I say?' and in government you wake up and ask, 'What do I do?'. Right. And those two things are very different.

So, I think yes to a degree. And towards the - the end, I would say we made much more use of Cabinet committees and so on. I mean, I'm a little sceptical as to what really makes the difference, though.

I mean, I think these structures are important. I mean, don't misunderstand me. And, as I say, we did definitely transition our mode of government over - over time. But that was also partly because over time I started to get a whole new generation of Cabinet ministers that shared my kind of reforming zeal. And so one thing that was becoming easier was, frankly, whereas at the beginning literally if I was not driving the change from the centre nothing happened or not a lot happened, towards the end what was - you know, you were getting ministers that were coming into positions that - that shared the agenda and were really striving to implement it. So, it became - yeah, we - we did change how…

But at - the biggest change, for me, was the focus of my own time and energy on the process of policy formation and implementation. Let me give you a very good example, which is around social exclusion; some of which the new government's taken on, some of which they haven't.

I came to the conclusion at the end that the problem was that there were a small number of very problematic families that had to be treated in a totally different way from the general, you know, "Welfare to Work" or whatever policies you had for the majority of the population. I came to the conclusion that there was a - a basic, kind of, sub-class of people to whom we had to pay special attention and have a very directly formulated policy around that problem.

Now, that was the product of an analysis and a way of working in government - actually, it came through Cabinet committees in the end that - that process, but - so an interaction between the centre and the ministry, but it was a quite different way of doing policy. So, we - we actually reached out outside the traditional policy options and we looked at government in a completely different way, and our policy in a completely different way. That was very typical of the last five years of governing.

So, in those last five years - because often people kind of - you know, particularly people within even my own party will say, look, in the first five years and before you came to came to office it was all, you know, how we wanted it to be, and then afterwards, you know, not just in foreign policy with Iraq and so on but actually in domestic policy people were kind of - thought I'd lost my bearings. Actually, I hadn't; I'd found them. And I'd found them in that type of policy-making.

Now, some of that came through the different way of using Cabinet committees, but actually most of it came from the appreciation that you had to think out of the box and differently to get to the right solution.

JOHN RENTOUL

Rosaleen Hughes.

QUESTION

Can I ask you about the fuel dispute in the autumn of 2000? How big a fright did it give the government and what lessons did you learn from it, both politically and administratively?

TONY BLAIR

It gave me a big fright. I mean, suddenly, you know, strike by some hauliers, and you wake up one morning and they say, 'Actually, the country's about to shut down.' No, that was not a good moment. And here's where I have to say, the way the system kicked in - the centre of government was brilliant.

Now, in a crisis, by the way - I mean, I think our civil service, you know, really does react in a very, very good disciplined way. And even though it was a nightmare, and we dropped, sort of, 20 points in the polls very quickly, you know, Lord! If we hadn't have had that centre of government operating in a strong way, with enormous input, actually, from the civil service and so on, we would've been in real trouble.

So, yeah. I think the lesson I learnt from that is that - and we actually had to apply similar things when we had the foot and mouth disease, which was the other, sort of, plague that hit us before that 2001 election - we had to - we actually learnt a lot about how to deal with crises. And then you need - by the way, you need absolute prime ministerial focus with the whole of the energy of government being brought together.

And, you know, again, frankly, in that instance you cannot leave it to the departments. I mean, we wasted time leaving things to the departments in those circumstances.

JOHN RENTOUL

Chap in red at the back there.

QUESTION

Matt Forde. I just wanted to ask, what hope is there of the Labour Party having a leader one day that won't be a former special adviser, perhaps, in the next 10/15 years?

TONY BLAIR

Right.

JOHN RENTOUL

Sorry, I didn't recognise you, Matt.

TONY BLAIR

Look, it's - this is not a specific point at all, because I support Ed's leadership and I support what he's doing, but I think there is a general problem in politics, not just in our system but in Western democracy - I mean, it's a far bigger topic this. But, I do think it's really important.

You know, I advise any young person who wants to go into politics today: go and spend some time out of politics. Go and work for a community organisation, a business, start your own business; do anything that isn't politics for at least several years. And then, when you come back into politics, you will find you are so much better able to see the world and how it functions properly.

So - But I - you know, this is an issue that they're debating in the US right now, in many places in Europe, and I do think there is a big gene pool problem with modern politics and how we get round I think is very challenging.

JOHN RENTOUL

Gus O'Donnell. [Lord O'Donnell, Cabinet Secretary 2005-11.]

QUESTION

Picking up on that very point, you said that you had your highest political capital at the age when you're least capable. So, how do we change the system for, maybe, selecting candidates and preparing ministers that actually means that instead of a small group of activists possibly choosing people who haven't got the background you were talking about? How do we open that up? Do you think - for example, you've mentioned about mayor's open primaries might be part of it.

TONY BLAIR

Yeah. No, I think you do have to look at this. I mean, this is a debate we should - a big debate to have about... I mean, I think there's a real issue to do with Western democracy, and how it matures and develops, today. And, yes, I think - because, you see, if I'm right in saying a lot of the solutions today are what I would call non-ideological in a twentieth century sense, then you've got a real problem if your political parties become ever more partisan.

And what you find in all Western democracies right now - you see what's happening in the US. I mean, it's an extraordinary thing, you know, you shut down the government over, really, a small group of people, able to bend the system to their will. And this is typical all over the Western world today. So I do think you have to look at, yes, new ways of involving people in the decision-making, which is why I think open primaries are probably the right direction to go.

I also think the concept of a political party today has got to shift. I mean, how you organise political parties - I mean, I think just - it's just completely different. People don't operate in the same way anymore; they live and work and think differently. And, you know, I think how you - the issue for political parties today is, how do you actually keep yourself in touch with the electorate in circumstances where, if you're not careful, a set of structures designed for a completely different world mean that you're in touch with a very limited group of people with a very limited set of opinions.

And the other thing I think that's fascinating to me is, there's so many ideas out there. I mean, you know, to be honest, I find it shocking how much I've learnt in this time I've left. I mean, it really is quite shocking; I mean, I wish I'd known it when I was there, but that's the way it is. But there is - there are so many interesting ideas going on out there. So, for example, one of the things I say to the presidents and prime ministers I work with - because sometimes they will say, "When will we get a healthcare system or an education system like yours," and I say, "Don't ask yourself that question. Ask yourself, from our legacy, what can you learn about the mistakes that we've made and the problems we now have. And secondly, technology alone should change completely the way you fashion these systems for today's world." I mean, technology should revolutionise education in itself. Leave aside all the other changes that are necessary.

So these are - this is the problem, you know, you definitely need to be thinking completely differently. And so my point about thinking differently is not a kind of civil service point and, actually, you know, Gus, as you know, is - you were an architect of many of the reforms that went through. There is a - I think there is developing a completely different culture within the civil service today, but it's the same for the politicians, because, you know, what other walk of life do you put someone in charge of billions and billions of pounds' worth of spending with no training? A bit weird.

JOHN RENTOUL

Nobody should be allowed to become an MP until they're 50, I think. Now that I'm 50, I think I can say that. Tom Robinson, did you have a question?

QUESTION

I had so many questions, and then that point's just thrown me; it was fantastic. Anyway, yeah, my name's Tom Robinson, former student of QMU. Of the many I can pick, I'll pick a humorous one, I think. Going back to Jon Davis's point, Mrs Thatcher once famously said, "Every Prime Minister needs a Willie." Do you think the reason why you didn't refer to Cabinet government as much as you did is because you didn't have one or you had too many?

TONY BLAIR

Well, we had, let's say, a few competing power centres in government, and that's the way it is. I mean, I actually had in - John Prescott in many ways was the person who helped me a lot with the party, and that was important. Because, you know, you've got to - politics is politics, and you've got to manage your political system, and managing your colleagues is very tough, because politics is a very competitive business. And people forget as well, you know, companies are like that; I daresay universities are like that. You know, only so many positions; people want them, you know. The most - I was amazed at the number of people who wanted to be Foreign Secretary, and I was even more amazed at the number of people who thought they could be Foreign Secretary. But, you know - and you have to say no.

So one of the problems you - I remember having this conversation actually with Alex Ferguson once when - discussing what you did with difficult people, and Alex's view was, you know, if they're difficult, out the door, you know. I said to him, "Yeah, but unfortunately, you know" - I said, "Well, I understand that, but what would you do if once you'd put them out they still had the right to be in the dressing room?" He said, "Well, no, that would be a problem," he said. And, you know, so it's - you do need your - you know, I think my problems in the end were perfectly natural, and, you know, the fact is, I survived 10 years with it, which in today's terms I think is quite a lot.

JOHN RENTOUL

Sorry, Charles Reiss.

QUESTION

Charles Reiss, formerly of the Evening Standard. In terms of coalition government, which, we've now had a peacetime coalition for some years, and in terms of what you were saying about changing ideologies or the lack of them, do you think there would be merit if coalition government here became more or less the norm, as it is in other countries, as well as widening your pool of ministerial talent? And, just by the way, do you think politicians ought to be trying to regulate the media?

TONY BLAIR

I don't really want to get into the media, I think, today, but I think the - you see, I think what happens in reality is that - like, when we won a huge majority - and I actually had the idea of having a coalition with the Lib Dems; I had a strong relationship with Paddy Ashdown, who I respected a lot. In the end, it wasn't really possible to put it together, but partly because we couldn't agree on policy issues, actually. I mean, I know there's some dispute about this, but my recollection very much was that they were prepared to cooperate on constitutional stuff but not on public service reform, and, for me, you know, you have to have both in it.

If you don't have a coalition between parties, what you tend to get is a form of coalition politics within the party. So, you know, people used to say to me, "Well, you know, you've got a majority of 160; you must be all powerful." It's not the way it works in the end. And, you know, I don't think I'm revealing any great secrets here, but, you know, obviously there was a certain coalition even between myself and Gordon Brown as Chancellor, who would take a somewhat different position on certain issues and how you came to an agreement in the end.

I think if it's a coalition of conviction, I'm in favour of it. If it's a coalition of convenience, I'm not sure you don't just end up in a situation where you institutionalise a tension between two different competing views, and that can often blunt the impact of government change. So I'm certainly - you know, as I say, I would have been in favour of doing it, but only in favour of doing it if there had been an agreement that allowed us to drive through more change faster.

JOHN RENTOUL

Talking of your coalition with Gordon Brown, don't you regret not building up someone else who could at least have fought a leadership election against Gordon Brown after you stepped down?

TONY BLAIR

Well, I'm not sure prime ministers can do that, really. You know, I think in the end it's - look, if you go back to that time, you know, he was obviously the person with huge stature and so on within the government and, to an extent, within the country. And, you know, I'm not sure it would have really been very sensible for me to try and engineer; someone else had to step forward. In the end, they didn't.

JOHN RENTOUL

Sorry, we're running out of time, but let's have a question from here. Microphone? Sorry.

QUESTION

Richard Evans, a friend of the Mile End Group. Tony, I'm not going to ask you the obvious question; I think a much more - better one. Could you give us your thoughts on the ever-complexities of foreign policy and when it's right to intervene and when it's not right to intervene?

TONY BLAIR

Well, that's a whole seminar in itself. It's - well, to state the obvious, it's incredibly difficult, and it's become more difficult. I think you intervene when the consequences of non-intervention are worse, and I think this is very difficult in the context of Iraq, Syria, Libya. My view is that today, wherever you have the presence of radical Islamic forces, whether of the Shia or the Sunni sort, then any intervention is going to be tough and complex and costly. On the other hand, when I look at Syria today, which is disintegrating, with terrible consequences for the whole of the region and the world, and where, by the way, almost as many people have been killed there now as in the whole of Iraq since 2003. And where you look at Libya, which, after all, is a regime change we brought about, so in a sense we should own the consequences. That is now exporting difficulty right across the region and down into the northern part of sub-Saharan Africa.

So, I think it's very, very hard this, and what it requires is a - is a deep and considered debate, which is not the debate that it often gets because I think when I look at the Middle East right now - I mean, I think there is an urgent need for the West to engage in a very serious fashion. In respect of Syria, Iran, Egypt, Libya, right across the whole of that northern part of sub-Saharan Africa, and if we don't, we are going to end up with a huge amount of problems in the future so, yeah, I think it's a - it's a very, very difficult debate, this because, you know, the fact is there are, when you lift the lid of these repressive regimes what happens is out comes pouring out a whole lot of hitherto suppressed tension of an ethnic and religious and tribal sort. But particularly in its religious form, which is why the other two foundations - one is about Africa and governance, and the other is about promoting respect between people of different faiths, and we are now in about 26 different countries with our programme there. But I think the position of religion in politics is the central question across the region and we should engage with it because it's going to impact us enormously.

JOHN RENTOUL

Thank you, Tony. I think we've overrun a little bit. Can I just say thank you very much for coming today and we hope we'll have you back in another two years. We hope to make this a regular event because I think there's obviously an awful lot more to discuss. You'll have to wait another two years for your questions. I'm sorry I was not able to get round to everyone but thank you very much for coming.

Courtesy of the Mile End Group and Queen Mary, University of London

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments