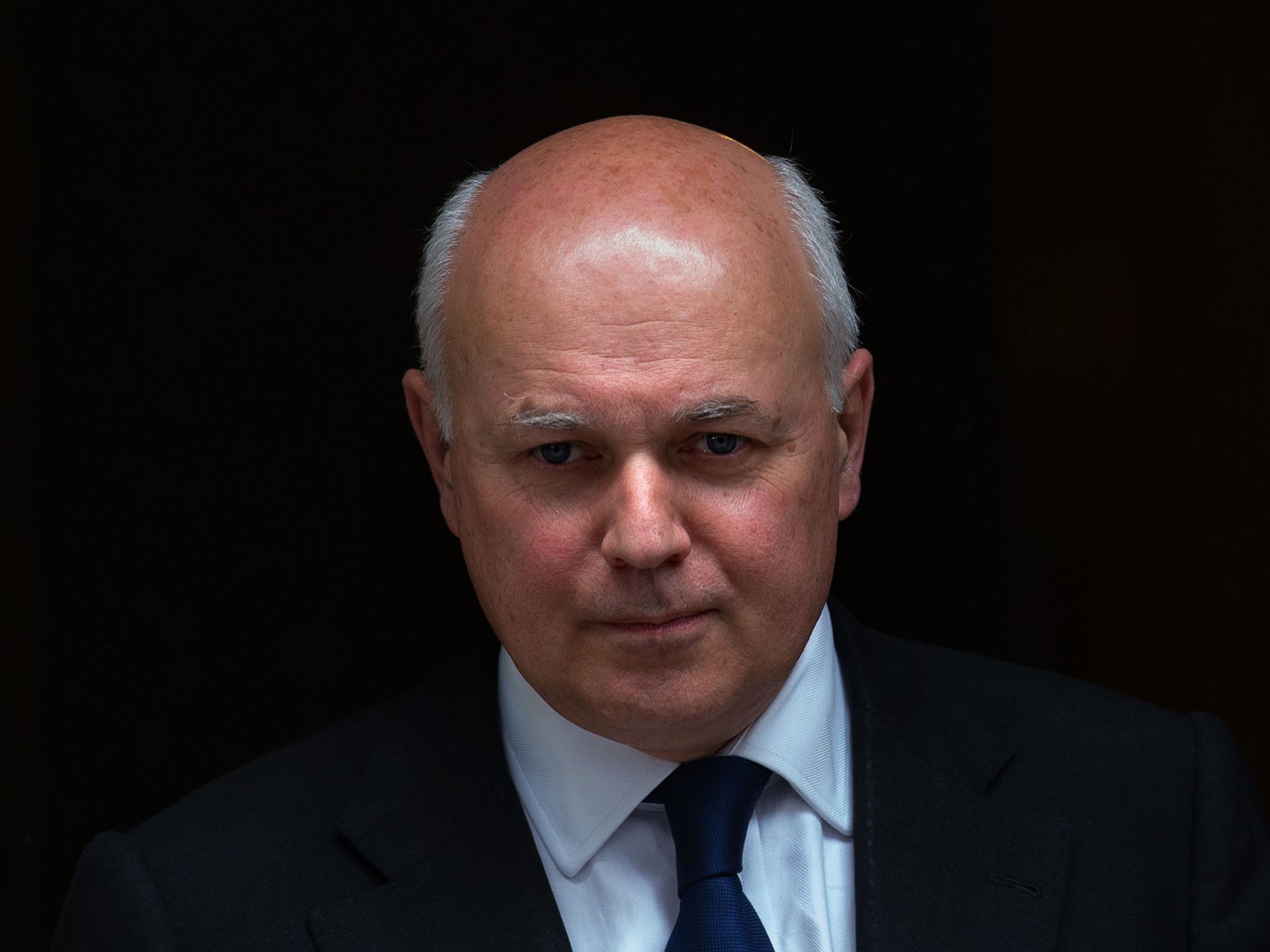

Iain Duncan Smith's Universal Credit scheme is throwing 90 per cent of social tenants into rent arrears

Mr Duncan Smith was explicitly warned not to implement the part of the policy causing the problem earlier this year

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Around 90 per cent of social housing tenants on the Government’s new Universal Credit benefits system are currently behind with their rent because of the way the scheme is structured, a new report by housing providers has revealed.

The research, conducted by two housing industry groups, found that a built-in seven-week wait for tenants before they could receive their first payment meant that nearly everyone on the scheme goes straight into arrears.

The extended waiting period blamed for the problems was brought in by Iain Duncan Smith despite explicit advice from the Social Security Advisory Committee in June of this year that it should not proceed for precisely the reasons described by the new research.

The National Federation of ALMOs and the Association of Retained Council Housing surveyed 36 social housing providers together covering 386,000 homes: they found that 89 per cent of the 2,000 tenants on Universal Credit in the survey were in arrears.

A third of Universal Credit tenants surveyed were also so deep into arrears that they had been put into special measures where their rent is paid directly to their landlord – a provision that is automatically trigged after eight weeks of behind rent payments.

The stark findings, first reported by trade publication Inside Housing, reveal an arrears rate three times higher than under the old benefits system.

The DWP hopes that all benefit claimants will ultimately be moved to Universal Credit, though the project has been beset by delays.

"[Arrears are] structurally built into the system. It’s just too long for people to wait,” Tracy Langton, the welfare reform lead for a Manchester-based council homes management organisation called Northwards, told Inside Housing.

In June the Social Security Advisory Committee warned against proceeding with the “waiting days” policy blamed for the arrears problem.

“The Committee expressed its concern about the introduction of waiting days into Universal Credit and the length of time claimants would have to wait until their first payment of benefit - in particular because Universal Credit includes the housing element - and recommended the Government reconsidered the policy,” according to a Government account.

The Government said it did not accept the Committee’s recommendations and that it wanted to implement the policy in order to limit access to the benefits system for people who were only briefly unemployed.

“The fundamental principle behind the waiting days policy is that social security is not designed to provide cover for moving between jobs or brief spells of unemployment,” the Government said in a response.

It also noted that the policy would save the Treasury £150m a year.

In the most extreme circumstances sustained rent arrears can result in tenants being taken to court, evicted, and made homeless. Heavy household debts, including rent arrears, have also been linked to depression and even suicide.

The policy could also have a negative effect on house building at the same time as large parts of the UK face a housing crisis. Social housing providers also rely on the income from rent to build new homes. The lower reliability of rental payments is expected to reduce their ability to increase their stock.

The Government’s Office for Budget Responsibility has already calculated that 34,000 fewer social homes will be built over the coming parliament because of other government housing policies that reduce the income of housing associations.

A Department for Work and Pensions spokesperson told the Independent: “These figures are highly misleading – our research shows that the vast majority of Universal Credit claimants are confident in managing their budgets and that the number of claimants in rent arrears is falling.

“For anyone who is having difficulties, we provide budgeting support and benefit advances, and can arrange for rental payments to be made direct to landlords if needed.

“Under Universal Credit, claimants are more likely to move into work and earn more.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments