What is the Good Friday Agreement?

Historic peace treaty brought republicans and unionists together after decades of violent political conflict in Northern Ireland, a period of trauma and turmoil known as the Troubles

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The Belfast Agreement, more commonly known as the Good Friday Agreement, was signed in Northern Ireland on 10 April 1998.

It effectively brought an end to the Troubles, which had raged for 30 years, and established a cross-community consensus around peace and the future direction of the region.

A quarter of a century on, we look back at the history of this hugely significant deal.

The Troubles

From the late 1960s, Northern Ireland was plunged into a brutal conflict between republicans who wanted the province to become part of a united Ireland and unionists who wanted it to remain within the UK.

Republicans and the wider nationalist community are mostly Catholic while unionists are mostly Protestant.

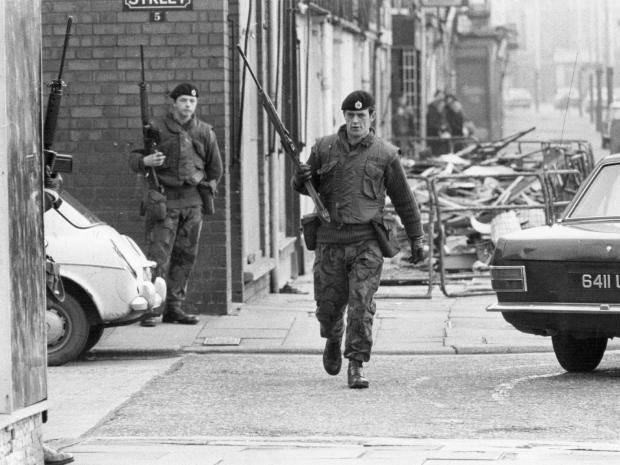

Violence was largely perpetrated by paramilitary groups on both sides, such as the IRA and the UVF, while others were killed by the British security forces after the army was deployed in the summer of 1969.

Of the 3,532 people who died, the majority were civilians, many of whom were killed in random tit-for-tat attacks across the sectarian divide.

For the majority of this 30-year period, Northern Ireland was under direct rule from Westminster.

Talks

After years of failed negotiations and backchannel discussions, progress was slowly made across the 1990s.

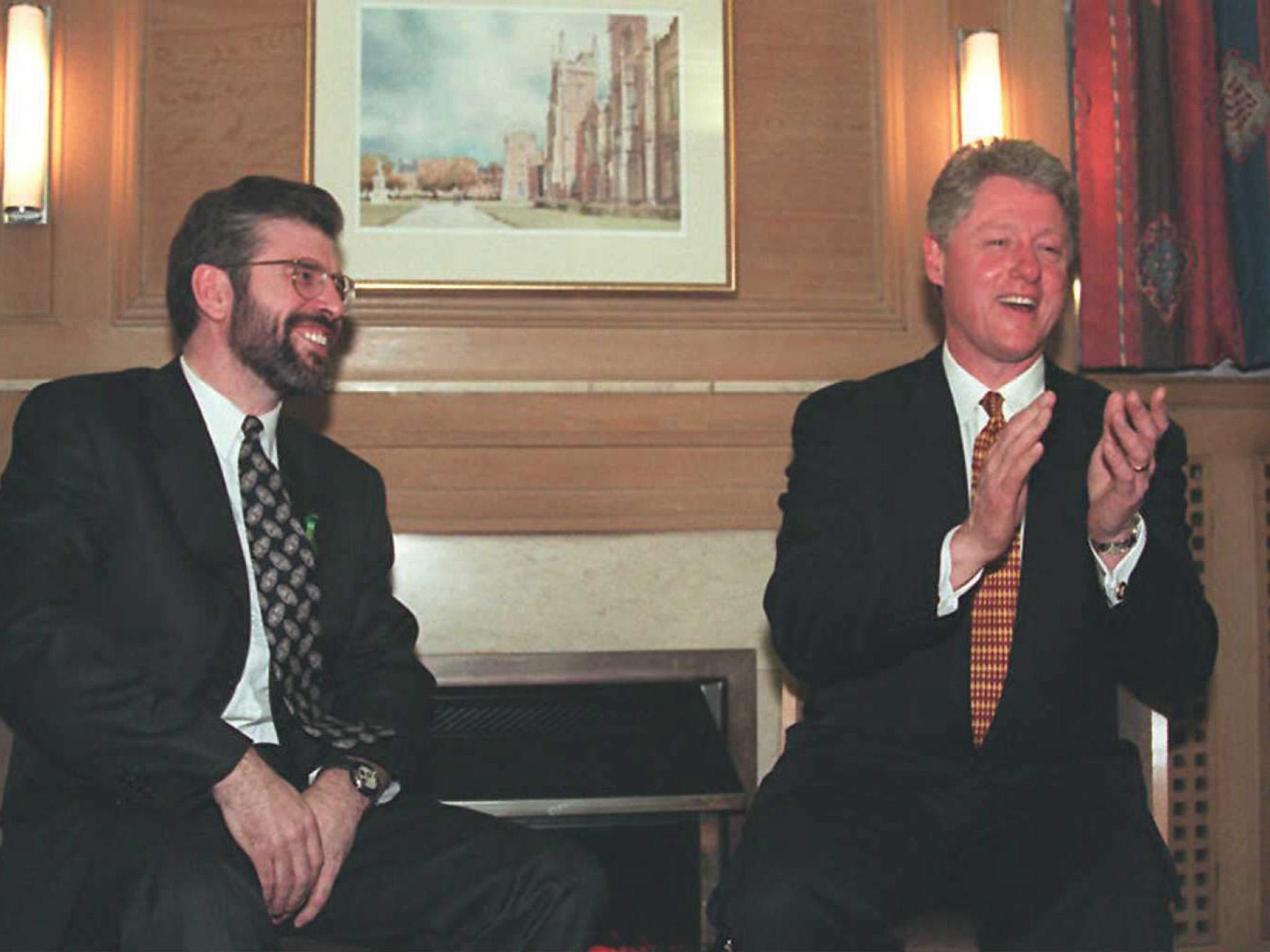

A dialogue between SDLP leader John Hume and Sinn Fein leader Gerry Adams made moves towards consensus across the nationalist community, while ceasefires announced by the IRA and loyalists in 1994 were also welcomed.

US president Bill Clinton took a keen interest in Northern Ireland and sent a special envoy in the form of Senate majority leader George Mitchell, who would eventually chair the talks between the parties and groups.

The situation was accelerated after Labour came to power in Britain in 1997 and Tony Blair saw the necessity of including Sinn Fein in the process, although the DUP walked out in protest over the inclusion.

Talks began in September 1997 and, in January 1998, Northern Ireland secretary Mo Mowlam made an unprecedented visit to the Maze prison to urge the support of loyalists who were imprisoned for paramilitary activity.

Similarly, as the political wing of the IRA, Sinn Fein were responsible for ensuring the support of republican prisoners.

In the final days, both Mr Blair and the Irish taoiseach Bertie Ahern went to Belfast to join the talks and the agreement was eventually announced by Mr Mitchell on the afternoon of 10 April 1998.

The agreement

The deal was formally made between the British and Irish governments and eight political parties from Northern Ireland, including Sinn Fein, the Ulster Unionist Party, the SDLP and the Alliance Party.

The DUP were the only major political group to oppose it.

The agreement acknowledged the constitutional status of Northern Ireland as a part of the UK, reflecting the wish of the majority of citizens.

But it also established a principle of consent: that a united Ireland could come about if and when a majority of people in the Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland wanted it.

In this instance, the British government would be bound to hold a referendum, and honour the result.

Three strands of new institutions were established in the agreement:

- A democratically elected Northern Ireland Assembly

- A North/South Ministerial Council for cross border issues

- A British-Irish Council and the British-Irish Governmental Conference

The Northern Ireland Assembly would be elected every five years and be led by an executive of ministers, which would require the participation of parties on both sides of the community divide.

Crucially, the agreement committed the parties to democratic and peaceful methods of resolving political issues, to using their influence to bring about the decommissioning of paramilitary groups and for security arrangements in Northern Ireland to be normalised.

The agreement marked a commitment to “the mutual respect, the civil rights and the religious liberties of everyone in the community” and Britain agreed to incorporate the European Convention on Human Rights into the law of Northern Ireland.

Referendums

The British and Irish governments agreed to hold joint referendums on 22 May 1998. The referendum in Northern Ireland was on accepting the Good Friday Agreement itself and 71 per cent of people voted yes.

The referendum in the Republic of Ireland was to amend the country’s constitution to relinquish its claim on Northern Ireland, acknowledging the new principle of consent.

An overwhelming 94 per cent of people voted to do so.

What happened next?

The years following 1998 remained turbulent and uncertain, with the Northern Ireland Assembly established, but periodically suspended, largely over concerns about continued paramilitary activity.

It took until 2005 for the IRA to decommission and, in 2007, Sinn Fein put their support behind the new Police Service of Northern Ireland.

By this point, the DUP and Sinn Fein had overtaken the UUP and the SDLP as the main unionist and nationalist parties.

The St Andrew’s Agreement of 2006 paved the way for the two major parties to enter power sharing together.

The relationship between Ian Paisley and Martin McGuinness, as first and deputy first minister, was a sign that Northern Ireland had truly changed.

The Presbyterian preacher and the ex-IRA commander were once sworn enemies but now suddenly working together in the same office and being nicknamed ”the Chuckle Brothers” as a result of their cheery rapport.

For the next decade, Northern Ireland experienced relative political stability due to the power sharing arrangement.

The Hillsborough Castle Agreement of 2010 saw powers over police and justice devolved to Northern Ireland, while the Fresh Start Agreement of 2015 saw further settlements on identity issues, as well as welfare reform and finance.

But in January 2017, McGuinness resigned his position in protest over a political scandal involving the new first minister Arlene Foster, thereby collapsing the executive.

He also cited long-term issues in which the DUP were failing to honour the commitments to basic equality laid down in their agreements.

McGuinness died months later and, although a new deal came close to being signed in February 2018, talks broke down.

A year later, the UK Parliament passed the Northern Ireland Act, to keep services running the absence of a functioning government, before the executive was reformed in January 2020 with Ms Foster as first minister.

Stormont’s power-sharing executive has since collapsed again due to further disagreements with the DUP, which has also declared its opposition to Rishi Sunak’s new Windsor Framework seeking to amend the Northern Ireland Protocol of the Brexit withdrawal agreement in the interest of improving trading conditions complicated by Britain’s departure from the European Union.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments