General Election 2015 explained: Voting

The final episode of our daily celebration of the facts, figures and folklore of British general elections

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.In the polling station

Most people who vote in tomorrow’s general election will vote in person, in one of around 40,000 polling stations that will be open from 7am to 10pm.

All voters should have received a poll card no less than a week before election day. You should present this at the polling station when you vote.

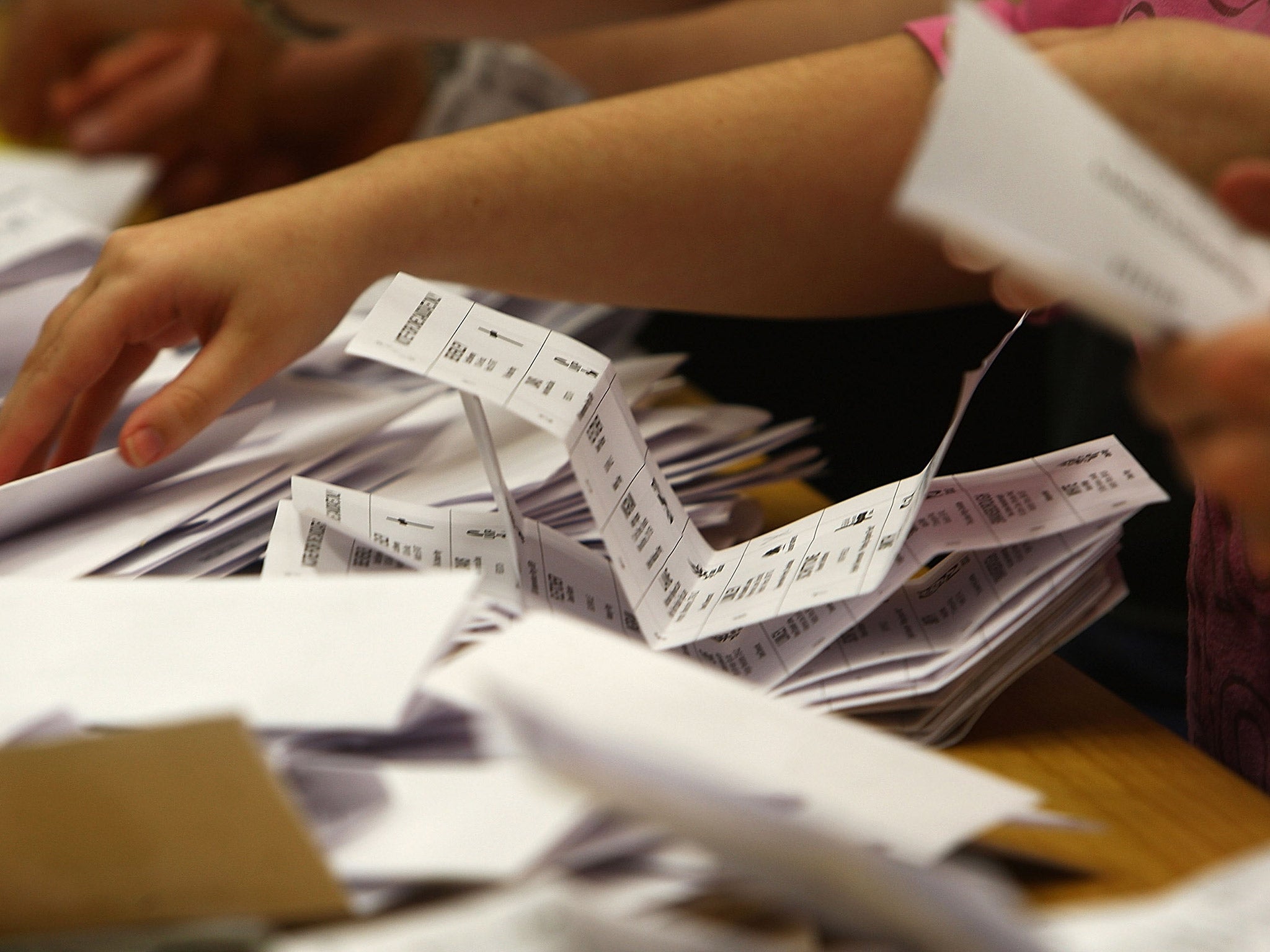

Each voter is then given a ballot paper on which to mark their vote. The paper bears an alphabetical list of all the candidates standing in that constituency.

In addition to your elector number, your ballot paper will carry an “official mark” which should be visible from both sides of the paper. This will usually be stamped with a special instrument immediately before it is given to you; but some papers may have a pre-printed mark or barcode instead.

It is thought that pieces of paper were first used for voting in Rome in 139 BCE.

Today, to prevent fraud, every ballot paper carries a Serial number as well as a unique official mark. This means that, although the ballot in UK elections is supposed to be secret, it is theoretically possible to trace each vote to the voter who cast it. It is, however, illegal to do so.

All ballot papers, counterfoils and related paperwork are sealed and stored securely for one year after the election. They are then destroyed.

Ballot papers in general elections are typically 15cm by 10cm in size. The Electoral Commission recommends that they be laid out in portrait rather than landscape format.

Until 1969, ballot papers listed only candidates’ names and addresses. They were then revised to allow candidates to include a small piece of information about themselves. Most use this space to indicate their party allegiance, but there is no legal requirement for them to do so.

Under Section 199B(4) of the Representation of the People Act (1983), ballot papers and nomination papers must be produced only in English – except in Wales, where they can be in English and Welsh.

Postal voting

A significant minority of voters will have opted to vote by post rather than in person. For the 2010 general election, 6,996,006 postal ballot papers were issued – an increase of 1,633,505 on 2005, and equivalent to 15.3 per cent of the electorate.

Well over 1 million of these were not returned before the close of polling, while a further 183,453 were spoilt.

This left 5,596,865 postal votes that counted towards the result of the election.

Postal voters are more likely to vote successfully than other potential voters. Postal voting papers were issued to 15.3 per cent of the electorate in 2010 – but postal votes represented 18.8 per cent of the total votes cast.

Postal votes have to be returned so that they arrive before 10pm on polling day.

Postal voting has been available on demand since 2000.

Voters in the North-east are almost four times as likely as voters in the South-west to vote by post.

Proxy voting

A proxy voter nominates someone else to vote, in person, on their behalf.

Anyone over 18 can apply for a proxy vote, although the deadline for doing so for this election (except for emergencies) was 28 April. Such a vote will be granted only if the applicant can provide a good reason for being unable to vote in person. Common reasons include: physical disability; living overseas; being a member of the Armed Forces; and being prevented from going to the polling station by compelling reasons of employment.

In 2010, there were more than 140,000 proxy voters.

E-voting

Evidence presented to the Commons Political and Constitutional Reform Committee suggested that 67 per cent of those who didn’t vote in 2010 would have been more likely to vote if they could have done so online.

In 2014 the Committee recommended that pilots of various e-voting methods should be run during the next parliament, with a view to making e-voting available as an option for all voters in the 2020 general election.

Methods of e-voting include: voting online, by email, etc; voting via interactive television; voting by text; voting at a polling station using a voting machine such as a touch-screen monitor.

Spoilt ballots

Ballot papers are declared “spoilt” if they have been filled in incorrectly.

In the 2010 general election, 81,879 ballot papers were rejected – slightly fewer than the 85,038 in 2005.

The main grounds for such rejections in 2010 were:

Want of official mark 640

Voting for more than one candidate 21,996

Writing or mark by which voter could be identified 2,522

Unmarked or void for uncertainty 50,964

Roughly three ballots in every thousand are rejected at the count. Spoilt ballot papers in recent general elections:

* 1979 0.38 per cent

* 1983 0.17 per cent

* 1987 0.11 per cent

* 1992 0.12 per cent

* 1997 0.3 per cent

* 2001 0.38 per cent

* 2005 0.31 per cent

* 2010 0.28 per cent

The returning officer in a constituency is the final arbiter on whether or not a ballot paper has been spoilt.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

0Comments