Frank Field told me: ‘Allowing Gordon Brown into No 10 would be like letting Mrs Rochester out of the attic’

Frank Field was a brave and compassionate politician who launched many successful campaigns in his life. But he was a political maverick who had a complex relationship with the Labour Party he represented as an MP for nearly 40 years. He was close to Margaret Thatcher, but only survived as a minister under Tony Blair for a year and clashed with Gordon Brown, as Simon Walters describes

Frank Field was a mass of contradictions. A Labour politician who preferred Margaret Thatcher to any Labour prime minister. An anti-poverty campaigner who wanted to reduce the amount spent on welfare benefits. A devout Christian affectionately known as “Saint Frank” who loved gossip and was capable of aiming unsaintly barbs at his political foes – as I discovered in my dealings with him over many years as a Westminster journalist.

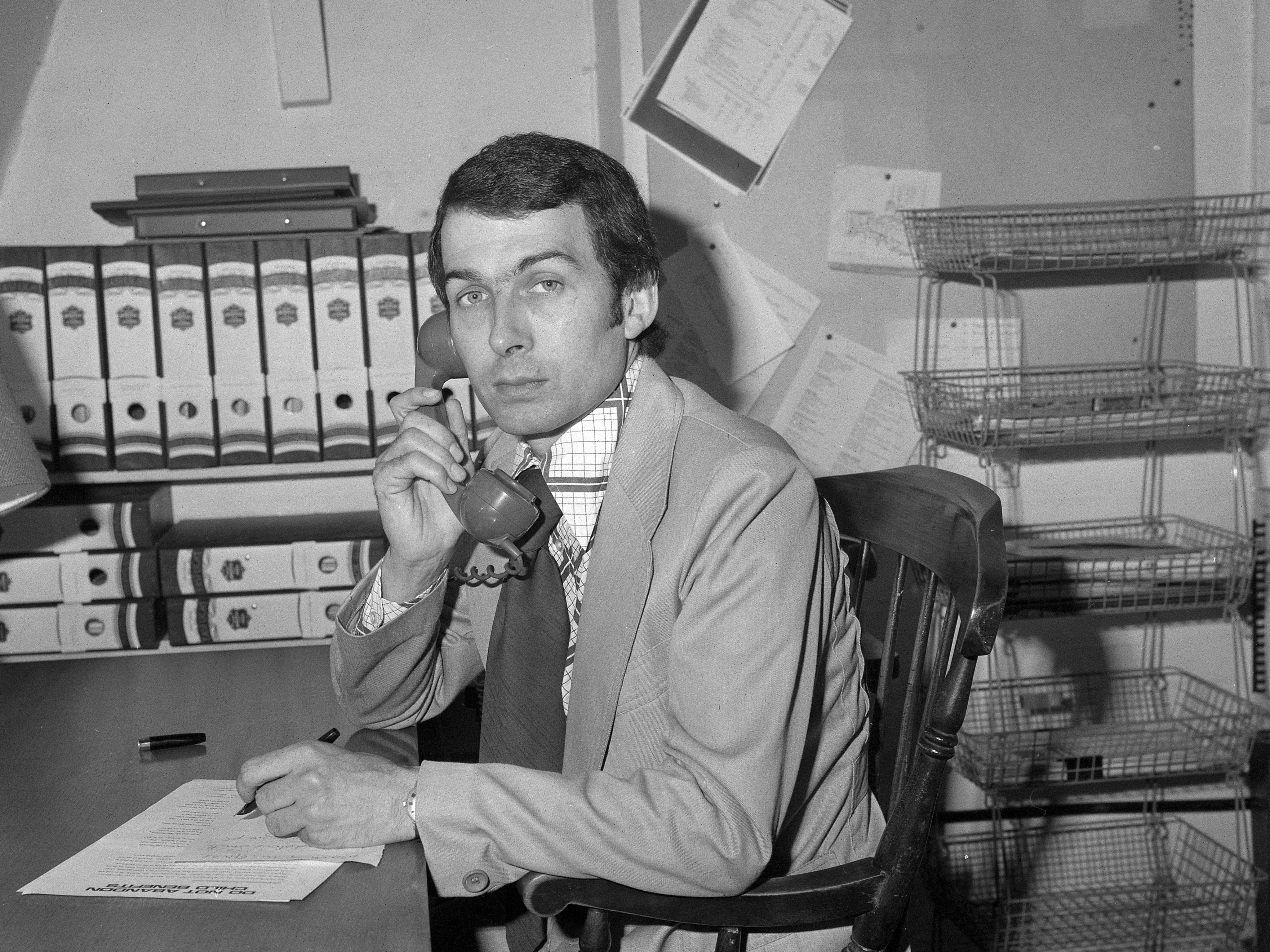

I vividly recall one of our meetings in early 2007. Tony Blair was coming to the end of his premiership and Field was determined to stop chancellor Gordon Brown succeeding him. He called me over and explained in forthright terms why he considered Brown to be unfit to rule – and why the public should know about it.

One particular phrase in the interview stood out.

Field said: “Allowing Gordon Brown into No 10 would be like letting Mrs Rochester out of the attic. He has no empathy. Tony Blair walks and talks like a PM. Gordon Brown doesn’t. That’s all there is to it.”

Brown, chancellor at the time, was reportedly not best pleased to be compared to the insane woman in the attic in Charlotte Bronte’s Jane Eyre. Field decided he had gone a bit far and apologised to Brown.

In the event, it didn’t stop Brown from becoming prime minister – though it could be argued his torrid time in Downing Street and subsequent election defeat bore out Field’s reservations. Field believed he had good reason to be cross with Brown. He blamed him in part for his own failure as a minister.

Field’s appointment as welfare minister during Blair’s first administration in 1997, with a remit to “think the unthinkable”, was seen as a watershed moment for Labour and its approach to the tangled, bloated and bureaucratic welfare state.

But it ended in acrimony after barely a year when Field’s reform plans were abandoned – or scuppered, depending on who you believe.

He resigned and spent the rest of his career on the backbenches. Field believed that Brown blocked his welfare reforms as part of his long-running political grudge match with Blair.

But there was more to it than that.

Not long after Field left Blair’s government, I asked a mandarin who had worked closely with Field and who admired him what he made of his resignation. He said: “Frank had all the right questions about what is wrong with the welfare system, but when you asked him to write the answers on a sheet of A4 paper he couldn’t do it.”

When Alistair Darling was sent to the welfare department in 1998 after Field left, with instructions to sort out the mess, he was shocked to find there were no plans for benefits reform to work on. He had to start from scratch.

Blair issued a warm tribute to Field this week, but read between the lines of his statement and you can detect more than a hint of the mandarin’s scepticism.

His true genius lay in the maverick campaigning skills that made him such an awkward fit in the stuffy confines of Whitehall

Field was an “independent thinker never constrained by conventional wisdom” who “stood up for the passions and insights he brought to any subject”, said Blair.

He has put it more bluntly in the past, saying Field’s welfare remedies “weren’t so much unthinkable as unfathomable”, adding: “Some are made for office, some aren’t. He wasn’t. Simple as that.”

Not that Field was Blair’s biggest fan.

Field complained privately that he needed cabinet status to have the political clout to deliver his welfare reforms – something Blair conspicuously refused to do, making him a lowly minister of state only. Field had no such reservations about his favourite prime minister, Margaret Thatcher, or “Mrs T”, as he called her.

Drawn to him by his churchgoing independent spirit and endless battles with Labour’s hard left, she struck up a remarkable friendship with Field.

Thatcher would use her influence to help him win extra cash for his Birkenhead constituency in Merseyside, knowing it would help keep his left-wing enemies in the area at bay.

Such was their closeness that in 1990, as Thatcher was clinging to power amid a growing Tory clamour for her to go, Field was one of the few allowed into her Downing Street bunker to see her.

He told her candidly she had no choice but to step down – or the “Tory creeps” who wanted her out would “tear her apart in public”.

Thatcher arranged for him to be smuggled out of the building. She resigned the next day.

Field’s failure as a minister does not mean his career in public life was also one – far from it. His true genius lay in the maverick campaigning skills that made him such an awkward fit in the stuffy confines of Whitehall.

These were as effective in Field’s twenties in his brilliant leadership of the Child Poverty Action Group charity as they were in his seventies when, as chair of a Commons select committee, he led an audacious campaign against shopping tycoon Sir Philip Green, who was accused of plundering the pensions of BHS workers.

Field defied wild legal threats from Green who was forced to stump up millions to plug the gap.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments