Downing Street accused of being 'systemically negligent' with national security secrets after name of ex-SAS officer finds its way into the public domain

Exclusive: Secretive DA Notice Committee claims No 10 'disregarded rules' over the identification of members of the Special Forces

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Downing Street has been accused of “systemic” negligence in its approach to the handling of sensitive information – by the body charged with keeping threats to national security out of the media.

No 10 is at the centre of an extraordinary row with the secretive DA Notice Committee after the name of a senior former SAS officer found its way into the public domain, The Independent can reveal.

The officer was named when he took up his post as military adviser to No 10 last year. The DA Notice Committee alleges that the name of the ex-SAS man was deliberately given to The Sun newspaper in direct contravention of rules governing the identification of present or former members of Britain’s Special Forces.

In minutes of a meeting in November – which have now been withdrawn after protests from the Government – the committee said the release of the name “appeared to have been caused by an adviser in No 10 who saw this disclosure as positive publicity and released the information with that in mind, apparently with no knowledge of the DA Notices”.

The minutes concluded: “It seemed that the release of the name was deliberate in order to make a political point.”

The committee’s acting chairman, Paddy McGuinness, the Deputy National Security Adviser for Security, Intelligence, and Resilience, said it wasn’t the first time that No 10 had “shown a lack of understanding of the DA Notice System” and that “the problem might be systemic and should be addressed”.

The committee, made up of Government members and media executives, added: “This was not the first breach of the DA Notice code by staff at No 10, but unfortunately –despite repeated offers to brief them on the system – they had thus far not chosen to take up the offer.”

After the publication of The Sun story in September, the committee wrote to the newspaper to “explain the possible damage that this had done to the personal security of the officer and his family”.

But the committee’s subsequent investigations exonerated The Sun and concluded that a No 10 adviser was to blame. Minutes of the committee’s November meeting, which contained discussion of that verdict, have now been taken down after the committee came under pressure from No 10.

It is understood that Downing Street disagreed with the committee’s finding on the SAS incident and was unhappy about criticism of No 10 officials.

Downing Street has insisted that the minutes were withdrawn because they contained a “number of errors”.

A No 10 spokeswoman said: “We thought the original minutes gave a false impression that No 10 was the source of that [SAS] information. There was a Cabinet Office internal inquiry into the source of that story and it concluded that No 10 was not the source.”

She added: “No 10 advised the journalist concerned to consult the Ministry of Defence on what they could or couldn’t report.” She denied that No 10 had been approached by members of the DA Notice Committee because of concerns about Downing Street’s systemic failings in handling information relating to national security.

Air Vice-Marshall Andrew Vallance, secretary to the committee, said the new minutes would be republished with an “addendum” which would cover additional information provided by the Government.

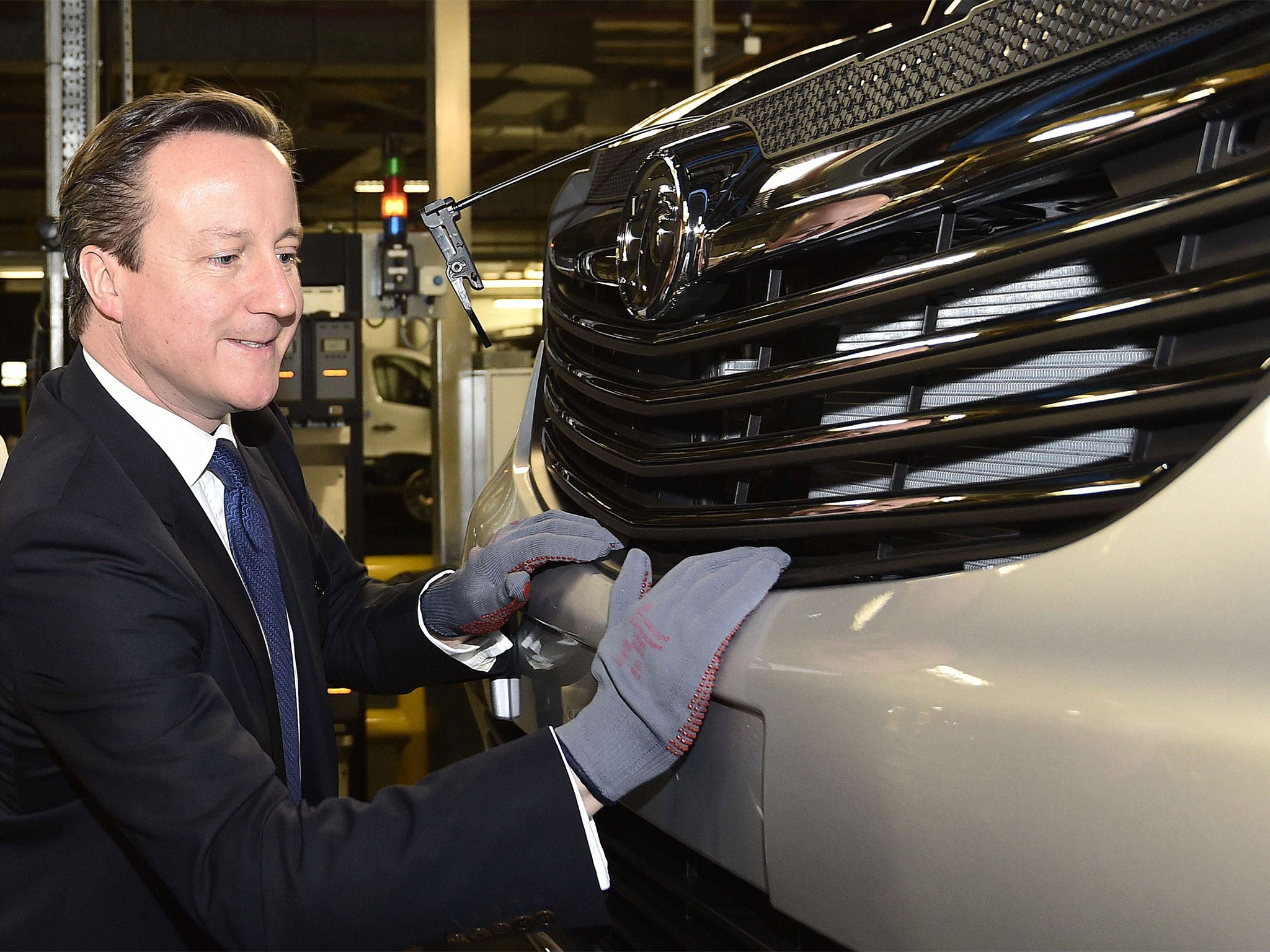

Whether or not No 10 was responsible for the publication of the ex-SAS officer’s name, the committee’s critical opinion of the attitude of No 10 staff towards information related to national security will embarrass David Cameron.

It is understood the previous incident to which the committee was referring directly involved the Prime Minister and his intervention in the Edward Snowden affair in which top-secret documents leaked by the US National Security Agency contractor were published in the UK.

Speaking in Parliament in October 2013, Mr Cameron urged newspapers to use “judgement and common sense” when deciding to publish material. “I don’t want to have to use injunctions or D-Notices,” he said. The reference to D-Notices concerned the committee as it is not an instrument of government.

Explainer: The DA-notice system

The system for preventing the media from publishing information that may endanger national security was established in the run-up to the First World War.

The Admiralty and the War Office decided they needed some means of stopping the press from publishing information which might be of value to a future enemy.

After informal discussions with the newspaper editors of the day, the then Secretary of the Admiralty met on 13 August 1912 with representatives of the War Office and the press.

They agreed a Defence Committee system on which members of the military and the press would sit. The editors secured assurances that only genuine matters of national security would concern the committee. And in turn the editors agreed to write to the Clerk-in-Waiting at the Admiralty before publishing sensitive material.

From the start it was intended to to be a voluntary system whose only purpose was to protect Britain from its enemies. The Committee exercised its function by sending editors notices requesting them not to publish details about operations or name certain individuals whose life may be at risk. It was an arrangement that worked well until 1967 when Prime Minister Harold Wilson made a misjudged attack on the Daily Express, accusing it of breaching two D-notices.

When the newspaper asserted it had been advised of no breach, an inquiry was set up under a committee of Privy Counsellors. The Committee found against the Government, whereupon the Government refused to accept its findings on the disputed article, prompting press outrage and the resignation of the Secretary of the D-Notice Committee. There are echoes of the Wilson row in the way the Cameron Government has misunderstood the role of the D Notice Committee – or the Defence Advisory Committee.

There are currently five standing DA Notices which advise the media against publishing certain kinds of military information. But the Government can’t force the press to follow the advice.

In the wake of the Snowden revelations, the current system is being reviewed and a report into its future operation is expected. Consultations with Government departments and media showed strong support for the continuation of a voluntary system rather than one that could force broadcasters and the press to submit to the will of the Government.

Robert Verkaik

Not-so-secret service: SAS identities

DA Notice 05 concerns the prohibition on the publication of the names of serving members of the SAS. It states that “identities, whereabouts and tasks of people who are or have been employed by these services or engaged on such work, including details of their families and home addresses” should not be made public unless they are the subject of an official announcement.

The committee says that this is because SAS personnel are targets for terrorists. But the committee also acknowledges its work has been made more difficult by a growing trend among retiring SAS soldiers to disclose links when taking up second careers.

The committee said in the November minutes: “persuading media outlets not to disclose the identities of lower-ranking intelligence officers had been made more difficult by a growing trend of retirees from these agencies and the Special Forces disclosing their former affiliation.” Clearly, this weakened the Secretariat’s case when trying to persuade media not to disclose names, but it was not something over which it could have any control.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments