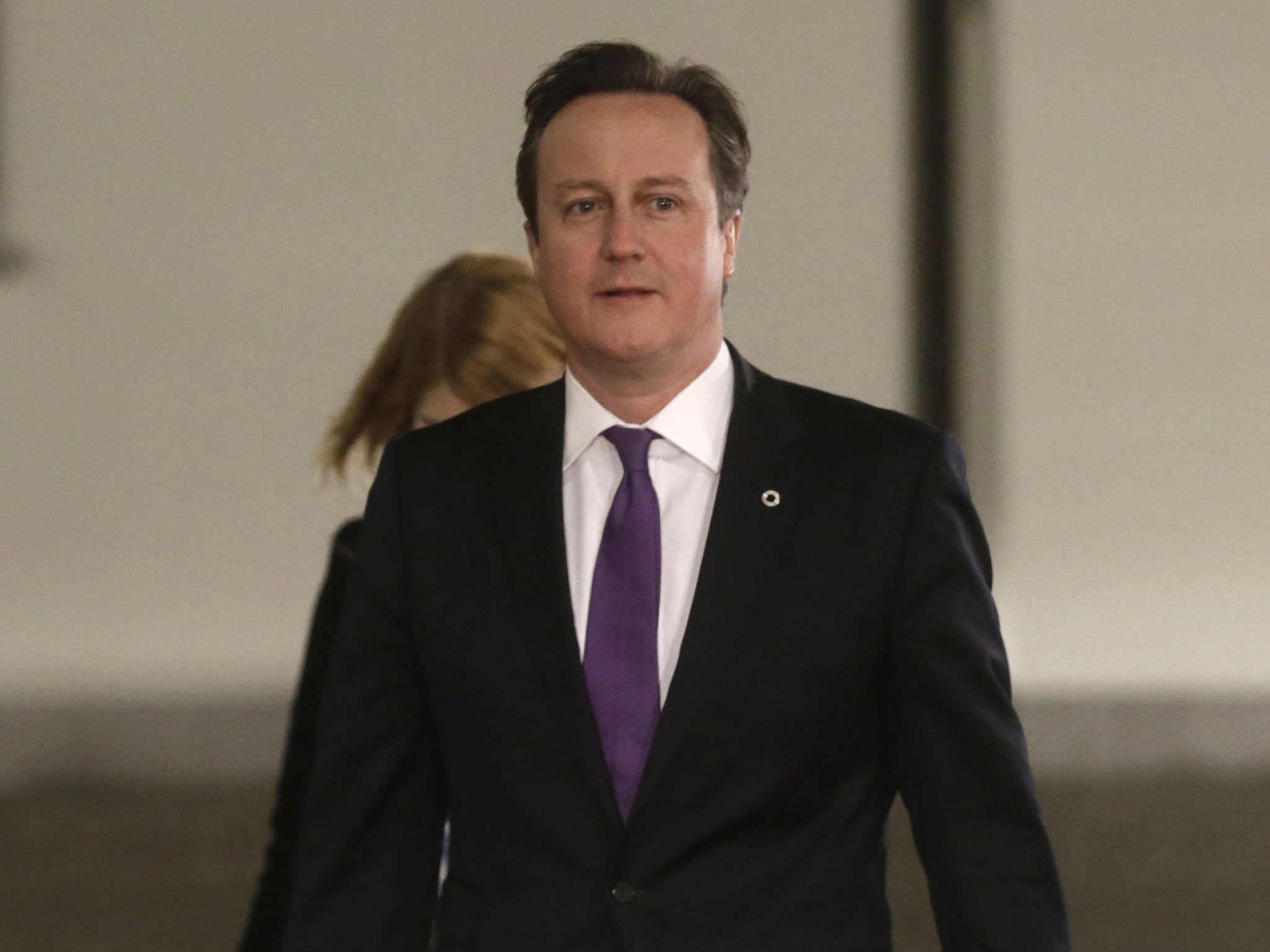

David Cameron accused of ceding ground on human rights to boost trade with China

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.David Cameron is preparing to water down Britain’s “ethical” foreign policy towards China as a necessary price to pay for increasing trade with the world’s second-largest economy.

The Prime Minister is due to fly to Beijing next week with the one of the largest business delegations ever assembled for a three-day trip to boost economic co-operation.

But despite scheduled meetings with both President Xi Jinping and Premier Li Keqiang, Mr Cameron is not expected to raise directly the issues of Tibet and human right abuses.

Instead he will seek to rebuild bridges with Beijing and assuage the Chinese anger that followed his decision last year to meet the Dalai Lama when he was in London.

“We have turned a page on the Dalai Lama issue,” said a Downing Street source yesterday. “This visit is forward-looking. It is about the future and how we want to shift UK-China relations up a gear.”

Mr Cameron’s stance towards China is in stark contrast to the position he took with Sri Lanka during the recent Commonwealth summit – at which he said his visit would “shine a global spotlight” on human rights abuses – and is an open recognition that there is an economic and political price to be paid for angering the autocratic Chinese leadership.

After Mr Cameron’s meeting with the Dalai Lama in May last year, Beijing cancelled a planned visit by the Prime Minister and summoned the British ambassador to protest that the meeting had “seriously interfered with China’s internal affairs”.

Since then the Government has strenuously sought to rebuild ties – and banned two ministers from having a private lunch with the Tibetan leader in the summer. But the British position has been condemned by human rights groups, who said the Chinese government was masterminding an escalating crackdown on activists and critics of Mr Xi’s administration.

The Foreign Office’s most recent annual report on human rights and democracy listed China as a “country of concern”.

It stated: “The use of unlawful and arbitrary measures to target human rights defenders included enforced disappearance; house arrest; restrictions on freedom of movement, communication and association; extrajudicial detention and harassment of family members.”

Some former diplomats have also questioned the new British approach. Rod Wye, former head of the Asia Research Group at the Foreign and Commonwealth Office, said that it was important to “maintain and protect” our values when dealing with China. “It should not all be about the good bits, but the bad bits as well. It is important that we speak about our differences,” he said.

Kerry Brown, an associate fellow at Chatham House and former British diplomat, told the Financial Times: “The whole situation has been poorly handled – 18 months ago Mr Cameron was the great defender of human rights speaking truth to China and saying the UK will act on principle. Now it seems to be about business and nothing else.”

Brad Adams, of Human Rights Watch, said Mr Cameron had to show he was willing to raise difficult issues with the Chinese.

And Eleanor Byrne-Rosengren, director of the campaign group Free Tibet, said: “China thinks that a combination of money and threats can ensure the silence of UK politicians. George Osborne’s excruciating visit last month was a real humiliation for Britain. Mr Cameron needs to restore our pride.

“China is not a rock: it does change and it will change its policy on Tibet if world leaders have the courage to hold it to account. Mr Cameron stands up for human rights in Sri Lanka and the right of self-determination in the Falklands. This is his chance to show China and the world that Britain stands up for justice everywhere.”

A poll commissioned by Free Tibet found that nearly 70 per cent of people believe that protecting human rights in Tibet is more important or as important as maintaining good trade relations with China.

Mr Cameron’s stance towards China’s human rights record is likely to be similar to that of George Osborne. Asked in October, he said: “We have to respect the fact that it is a deep and ancient civilisation that is tackling its own problems and going about it in the way it thinks is appropriate. We can point out where we would do things differently, but I think we do need to show some respect for that.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments