Can the Women's Equality Party translate its passion for change into votes in 2016?

The Women's Equality Party was founded on a wave of frustration in 2015. But can the three founders succeed in putting action before 'faffing' and principles before politicking? Nick Duerden meets them in their makeshift HQ to set the agenda over sushi

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.It's lunchtime on a curiously balmy winter's day, and the three women on whose collective impetus the Women's Equality Party thrives are sitting in an ad hoc boardroom in their London Bridge HQ as, directly outside the window, the 13:16 to Charing Cross rattles by.

When you learn that this isn't really their HQ at all, you are privately relieved for them: paint peels from the wall, and the smell is faintly fungal. They don't have a proper one yet, they explain, because they can't afford one. “Can I emphasise just how much money everything costs?” says co-founder Sandi Toksvig with an air of impatience that, today at least, pervades the atmosphere. For the past few months, they have been sharing office space with the people from Index on Censorship magazine, one floor up from a physiotherapy centre. At least some of this year will be spent finding office space of their own.

Toksvig, midway through an Itsu lunch, is explaining how 2015 took an unlikely, if ultimately inevitable, sharp turn for the three of them – her, the writer Catherine Mayer and the journalist Sophie Walker – when they suddenly found themselves fronting a new political party.

“We didn't wake up on 1 January 2015 and decide that we were going to do this,” she points out, adding that she was nevertheless increasingly exasperated and frustrated by a political system that no longer represented her, and so what else was she to do?

Elsewhere, Mayer, a long-time friend of Toksvig's, was feeling much the same. In March, she was attending the Women of the World festival in London – today she wears its acronym, WOW, in thick pink plastic as a necklace – to give a talk on politics, and what the main parties were doing for gender equality – or, more pertinently, what they weren't.

“I heard one woman in the audience saying she was so disillusioned with politics she might not even vote [in the upcoming election],” Mayer says. Mayer brooded on this, then posted on Facebook that evening that she was thinking of founding a women's political party: was anybody interested? Many were, among them Reuters journalist Sophie Walker. “I'm in,” Walker wrote back.

Mayer later learnt that Toksvig was already in the process of doing something similar herself. Toksvig even had a name ready: The Rescue Party, its motto: women and children first. “In a sense,” Mayer says to Toksvig, “you and I have been having conversations about how we've been disenchanted and frustrated [with the existing political system] for years. We just got tired of waiting, didn't we?”

And so in March, the Women's Equality Party was born, unofficially at first because there is much bureaucracy and red tape to wade through before official party status can be granted. “Did you know that?” Toksvig says, frowning. “I didn't know that. This whole process is absolutely designed to keep the current tribes in politics in place, and to stop anybody else from trying to affect change.”

Nevertheless, this strictly non-partisan operation had momentum in their favour, and a groundswell of public support. Through word-of-mouth and social media, the party quickly took off, despite little money and even less know-how. In June, they had a fundraiser, bagging themselves a wealthy (male) entrepreneur – one Maurice Biriotti – as donor, and by July they had appointed Walker as their leader.

There have always been peripheral political parties, of course, some of whose existence feels necessary, others distinctly less so, but the WEP had hit a headline-grabbing nerve in much the same way that Ukip did, albeit for radically different reasons. Their issues were more issue, singular: gender equality across the board – in pay, childcare and parenting. They wanted to eradicate the sex industry, and they wanted 50-50 political representation. In this they had their work cut out: just a quarter of those standing for the 2015 election were women, and of the 650 MPs elected, a mere 191 were female. Two-thirds of the current Cabinet are men, and Jeremy Corbyn's shadow Cabinet failed to appoint a woman in any of the top jobs. Just 450 women have served as MPs in British political history.

But, argues Walker, this can be easily overturned – and within the foreseeable future, too. Simply by making sure there are all-women shortlists in the former seats of at least two-thirds of retiring MPs, she says, and the House of Commons will achieve parity by 2025.

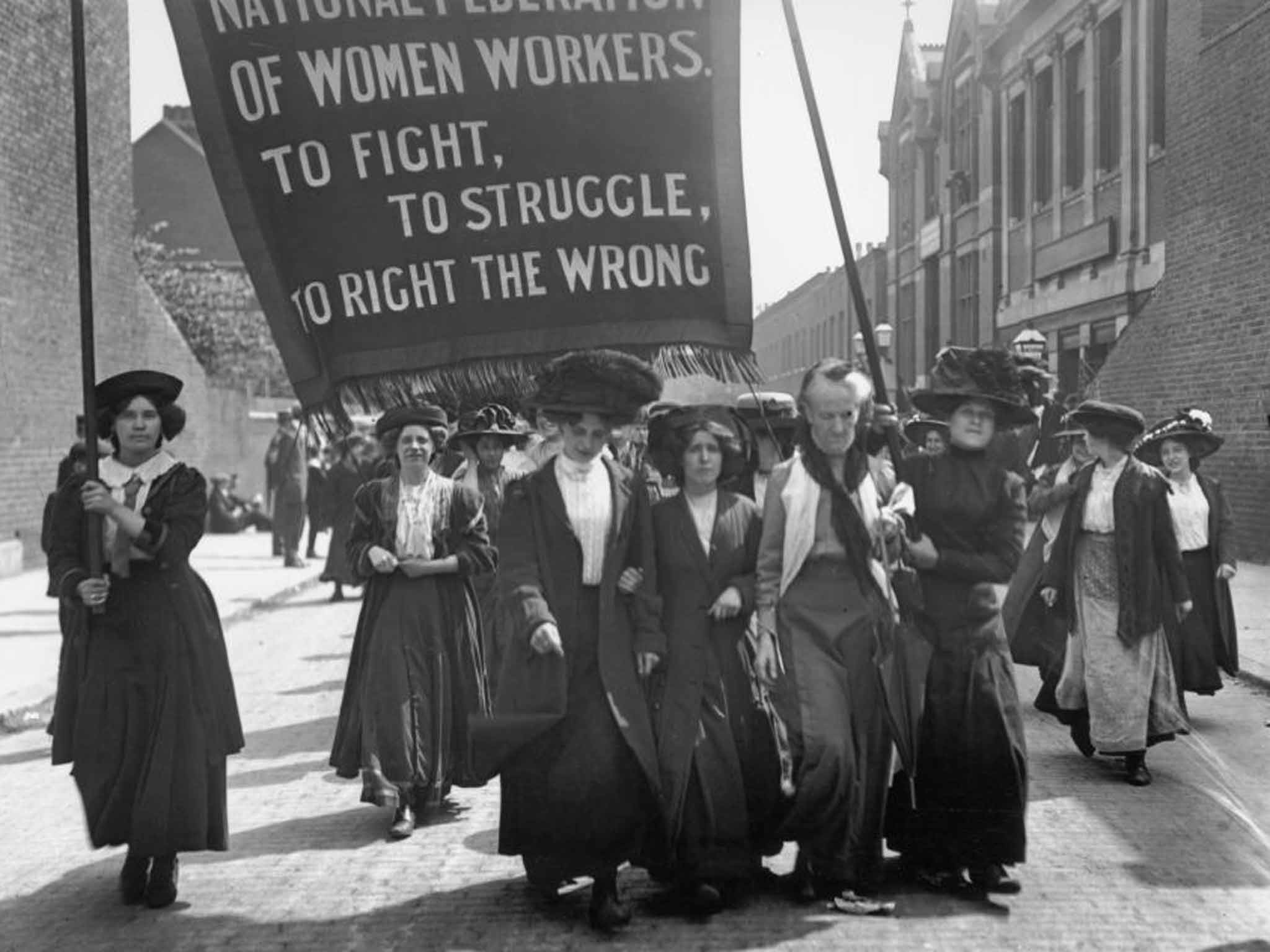

The fact that the party garnered so many column inches so quickly shouldn't come as much surprise: the combination of two media types and a celebrity luvvy was never going to struggle in getting their initiative noticed. By the time the film Suffragette, starring Carey Mulligan and Meryl Streep, arrived in cinemas in October, the WEP felt positively righteous. Ten months on, they now have more than 45,000 members in 70 branches nationwide. This year, they will put forward candidates for MPs in the London assembly, as well as Wales and Scotland.

“It cost us £31,500 to get names on ballot papers for the 2016 elections,” Toksvig says; a sum the party didn't have. They gave themselves six months to raise funds – through party membership fees and crowdfunding – and managed it in just six weeks. This spurred them on further still, but Walker insists that they are not getting ideas above their station. The WEP, she insists, will be a finite proposition. “Ideally, there will be no need for our party one day; the other parties will have taken our policies on board. But give us your vote in the next two elections, and let's see what we can do.”

In their temporary HQ, the chemistry between the three women is palpable. They complement one another, are one another's foils. Walker is tall and dynamic; she speaks in italics, as if every sentiment uttered requires her to punch the palm of one hand with the fist she has made of the other. Like an MP, in other words. She has a daughter on the autistic spectrum and says she is used to lobbying and fundraising for greater understanding: “It helped me see how bad we are at embracing diversity,” she says.

Mayer, who is married to Andy Gill, the singer from 1970s' post-punk act Gang of Four, recently wrote a biography of Prince Charles that proved not to be the hagiography the Palace may or may not have been anticipating. She is under the weather today, and has all but lost her voice. Her answers are whispered, and she threatens to use sign language. Toksvig, married with three grown-up children, is wry and deadpan, and affects a perpetual impatience toward a world she sees as going to the dogs unless we act now. She is clearly the Party's ire, her comrades the fire.

Running a start-up political party quickly became a wildly time-consuming job for all three. Both Walker and Mayer stepped back from their full-time writing positions, and Toksvig gave up her role on Radio 4's News Quiz after 23 years on the show, for the past nine as host. (Though she isn't facing penury just yet: she was recently announced as the new host of QI.) Of the three, only Walker draws a salary from her WEP work.

When I suggest that this is quite a sacrifice, it is Walker who answers first, in italics again, to match her raised voice. “No it isn't! It's got to be done! What were we to do otherwise? Sit and do nothing?”

Toksvig harrumphs in solidarity. “I just got so fed up with waiting. I couldn't sit and shout at the television any longer.” She says she has friends on both Tory and Labour benches in the House of Lords, but that all they indulge in is talk, not action. “Enough with the empty rhetoric!” Walker says, Toksvig adding: “We need non-partisan action, and we need to offer good solutions because these are not intractable problems.”

Though gender equality is a commonly heard rally cry among MPs, real traction is rarely made. There is a suggestion that while the subject does matter – and not merely to women – it is not as much of a vote-winner at general elections as the economy, or the NHS.

“We want to tell them to stop faffing,” says Toksvig. “I'm too old to do faffing any more [she is 57]. Stop faffing, and get on with it. The principles we are putting forward are so pragmatic that I cannot see why anybody wouldn't do it.”

If the business of setting up a political party has made for a steep learning curve, then so too has withstanding the invective that has come their way. Perhaps not so much for Toksvig – she is a reluctant old hand at dealing with hate mail, an apparently inevitable consequence of being both famous and gay – but for Mayer and Walker, it's all still uncomfortably novel. Much of the Twitter-led abuse that comes their way is due, Mayer says, to “being female and a little bit in the public eye”. But then this is all grist to their mill: another prevailing party issue is to campaign against violence towards women, particularly of the 21st-century, trolling kind.

“There are serious issues about how women are treated in the public arena,” Toksvig says. “You are not allowed to be this abusive to a woman in a public house, so you shouldn't be allowed to be abusive in a public space.”

The fact that women are continually abused online, often for feminist-related issues – among them the historian Mary Beard, and Caroline Criado-Perez, the woman who was attacked for suggesting more women of note should grace our currency – offers what the WEP believe is tangible proof that the main political parties aren't doing enough about it.

“I know I'm going to get a lot of shit thrown at me,” says Walker, “and I'm surprised there hasn't been more of it yet, frankly. But a part of me just says: bring it on, because we are going to do something about this.”

To this end, she steadfastly refuses to be drawn into the non-political agendas that invariably face female MPs: she won't discuss how she dresses (more stylishly than M&S) or her hairstyle (it used to be longer), nor will she engage in the Daily Mail's Sidebar of Shame.

Toksvig looks up from her lunch. “Sidebar of Shame? What's that?” Walker explains, and Toksvig looks bemused, then scoffs. “Why would I know anything about that? There are books to read.”

While knee-jerk criticism can be easily brushed aside, if not fully ignored, the other kind – the kind routinely given out to all MPs that dare to represent us – cannot. Not everyone thinks the Women's Equality Party is a force for good. There are corners of Mumsnet that believe they are merely middle-class white women focusing on the narrow issues that affect other middle-class white women, while sections of the broadsheet press remain convinced that a vote for the WEP is a wasted vote, hurting Labour and what remains of the Liberal Democrats while benefiting the Conservatives, and that their arguments over continued gender equality and pay are fundamentally flawed, outdated and untrue.

Cathy Newman, Channel 4 news anchor, admits that she too wasn't immediately won over when the party launched. “I thought their aims were laudable and I wished them all the best, but I was sceptical because I've always questioned why you would put women's issues and rights aside,” she says. “This should be something for the mainstream parties to take care of. But then I thought about their policies, their justification of why they need to exist, and I really do think they have a point. Like Ukip before them, they've moved the political agenda and changed the terms of debate.”

And the longer that the mainstream parties fail to address gender policies, Newman continues, the more it seems likely the WEP will grow. “I suspect that the reason they don't end up doing anything is because those parties are still run, by and large, by men, and so these are not issues that they think about regularly: equal pay, childcare, harassment. But they are bread and butter to women who have to face them every day.”

Toksvig insists that their critics are of little relevance: “What people think of us in the public sphere isn't something we spend a lot of our time thinking about, to be honest.” Instead, they keep campaigning to bring their policies to the forefront, and to encourage – and bully – the other parties into paying full attention. Which may already be happening. “All the main political parties have come to talk to us,” says Mayer. “So they are taking notice.”

This year will determine, for many, just how seriously to take them. Newman, for one, isn't predicting their immediate success. “I can't see them winning swathes of seats, but if they can get the mainstream parties to finally take action on issues on equality, then perhaps their job is done.”

But how quickly they will achieve their aims remains open to question. “I'd like to think they will have no reason to exist in years to come,” Newman says, “but they might need to stick around longer than they think.”

One of the most persistent criticisms they face is that they are not a political party at all so much as they are a “middle-class ladies campaign group”. To this, Toksvig offers the most world-weary of sighs, puts down her chopsticks, and sits up straight.

“The difference between a pressure group and a political party,” she says, “is that we, as a political party, can hurt the others at the ballot box, and that is absolutely our intention. Over nine million women failed to vote at the last election [out of 17 million people in total]. So let's find those people and get them to engage in the political system again, shall we?”

The WEP Fundraiser, featuring Toksvig, Jo Brand and Caitlin Moran, will take place at Central Hall, Westminster, on Thursday

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments