Budget 2016: Richest 10 per cent of households easily the biggest beneficiaries, analysis finds

George Osborne could also face Commons defeat over planned £4.4bn cuts to disability benefits

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

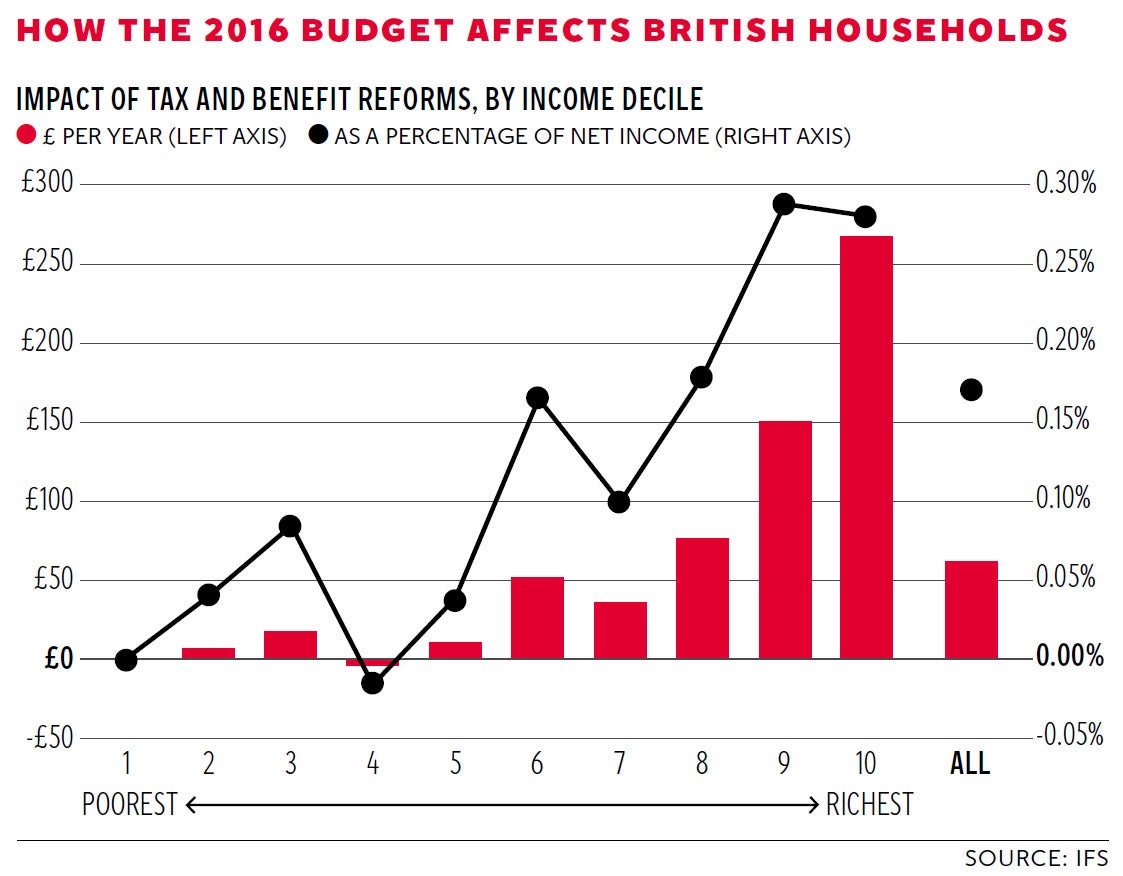

Your support makes all the difference.The regressive reality behind George Osborne’s “Budget for the next generation” has been laid bare, after analysis of the Chancellor’s latest tax and benefit decisions showed the richest 10 per cent of households are easily the biggest beneficiaries.

The Institute for Fiscal Studies and the Resolution Foundation both pointed to calculations showing a cash gain next year of more than £250 a year for the top decile, as a result of the Budget.

The next richest 10 per cent will get £150 extra, and the next richest decile after that receives a benefit of around £75. In contrast, the gains for those in the bottom half of the income distribution are negligible – and concerns were growing among Tory MPs that their Chancellor’s cuts in disability benefits will add to financial worries among the most vulnerable in society.

The regressive result of the Budget was largely a consequence of the Chancellor’s decision to increase the threshold at which the higher 40 per cent rate of income tax becomes payable – by £1,100 – to £45,000 from April 2017.

“Eighty per cent of the gains [go] to the top half of the income distribution and nearly half [go] to the top 20 per cent,” researchers at the Resolution Foundation think-tank said. They labelled the decision to increase the higher-rate threshold “particularly misguided” at a time of increasing strain in the public finances.

The Office for Budget Responsibility had revised down its forecast of the productivity growth potential of the UK economy in the years ahead, prompting the substantial downgrades to estimates of tax revenues over the next five years.

This compelled Mr Osborne to pencil in a big cut in spending in 2019-20 to hit his self-imposed “fiscal mandate” of running an absolute budget surplus in that year.

However, the IFS said that his chances of achieving a surplus by the end of the parliament now stand at just 50-50.

The IFS director, Paul Johnson, said that the effects of the OBR’s downgrade would extend beyond the public finances.

“That loss largely arises from changes in assumptions about future productivity growth leading in to lower economic growth over the rest of parliament,” he said. “If the OBR is right about that, we should all be worried. This will lead to lower wages and living standards, not just lower tax revenues for the Treasury.”

The impact of the Budget reinforces a regressive trend from this Government since last May’s election.

Taking all of Mr Osborne’s post-election tax and benefit measures together, the IFSon 17 March estimated that the incomes of the poorest 10 per cent of the population are set to fall by 7 per cent by the end of the parliament and the second poorest decile by 9 per cent. That equates to an annual loss of £1,300 and £1,600 respectively.

The incomes of the richest 10 per cent, however, will remain unchanged.

Analysts have already warned that Mr Osborne’s attempt to push the public finances into surplus by 2019-20, partly by squeezing the welfare bill by £12bn, is set to send inequality and child poverty rates up sharply again over the coming years.

One of the welfare savings that keeps Mr Osborne on course to achieve his budget surplus in 2019-20 is a new tightening of access to personal independence payments for the disabled.

Labour’s shadow Chancellor, John McDonnell, argued that people with disabilities were paying for tax cuts for the rich. “We would reverse them, it’s unacceptable,” he said.

The number of people paying higher-rate marginal income tax has risen by almost three million in the past 25 years as successive chancellors have failed to increase the threshold in line with wage inflation – the total now stands at 4.65 million.

However, around 80 per cent of income-tax payers continue to pay income tax at the basic 20 per cent rate. So reducing the numbers affected by the higher rate still disproportionately benefits those at the top of the household income distribution.

The Conservative manifesto committed the party to raising the higher-rate tax threshold to £50,000 a year by the end of the parliament. Assuming that manifesto promise is kept, future Budgets from Mr Osborne will mean more cash gains for those towards the top of the income distribution.

Another tax decision that favoured the well-off in the Budget was Mr Osborne’s surprise decision to reduce the main rate of capital gains tax from 28 per cent to 20 per cent. This tax is only payable on gains above £11,000, meaning that it is the already wealthy who are most likely to benefit.

Factoring in this tax break, which will cost the Treasury £735m a year by 2020-21, the Resolution Foundation estimated that the average income of the top 10 per cent of households would rise by £600 a year by the end of the decade.

The IFS forecast last month that, over the rest of this decade, household income inequality will increase, driven in large part by the Conservatives’ tax and benefit policies.

It also projected absolute child poverty to rise from 15 per cent to 18 per cent, thanks entirely to welfare cuts for families with three or more children.

The Chancellor cited the “next generation” 17 times in the Budget. But many argue that government policy since 2010 has consistently favoured the interests of older generations.

The IFS estimates that young adults took the biggest knock from the 2008-09 recession and have still not recovered.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments