Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) revealed an ocean of red ink alongside George Osborne's fourth Budget. The forecaster expects the Treasury to have to borrow more over the next five years than it anticipated just three months ago when the Chancellor delivered the Autumn Statement.

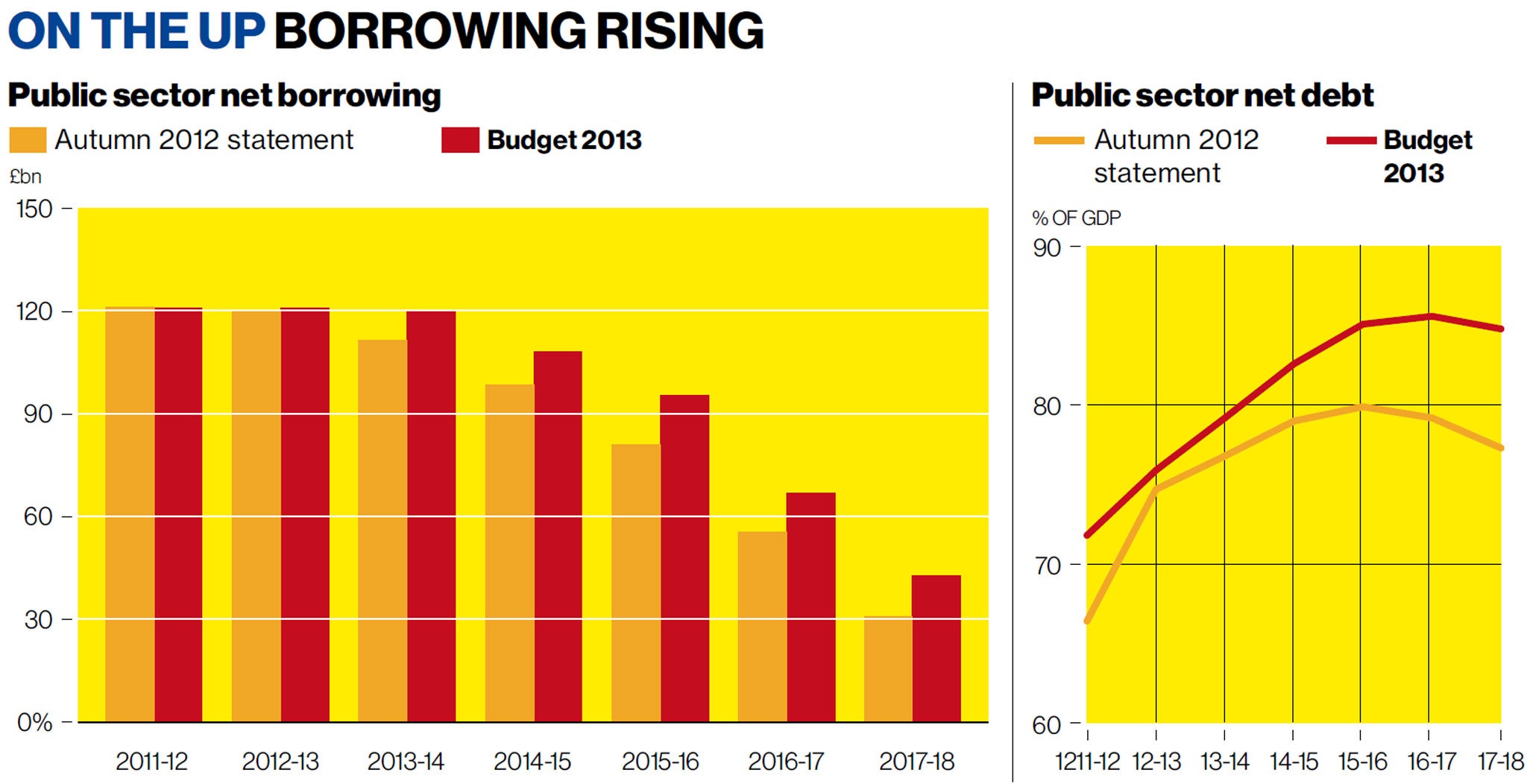

Stripping out the various accounting changes such as the nationalisation of the Royal Mail pension scheme and various cash transfers from the Bank of England, the total deficit for this present financial year is seen as coming in at £120.9bn or £1bn more than the forecaster expected in December. That's a fairly modest rise. But it's in future years that the overshoots really start to kick in, as the chart shows.

Borrowing in 2013-14 has risen by £8.3bn on December's forecast. In 2014-15 borrowing is seen as £14.3bn higher. In 2016-17 the shortfall is £11.4bn and in 2017-18 it is £11.8bn. That adds up to a grand total of £56.7bn.

That's a sum greater than the UK's annual defence budget. And that's the deterioration since December. If one compares the projections for borrowing over this Parliament with what the OBR forecast at the time of Mr Osborne's first Budget in June 2010, one sees more than £245bn in extra borrowing. That is a useful prism through which to evaluate Mr Osborne's claim that he is getting to grips with Britain's debts.

The main cause of the deterioration in the OBR's forecast is weak outlook for tax receipts, which are seen as £62.3bn lower than it expected in December. That shortfall is slightly offset by faster reductions in spending over the next five years of around £2.9bn.

Despite all this red ink, the OBR says the Chancellor is still on course to meet the main requirement of his self-imposed fiscal mandate, which is to eliminate the structural deficit – the part of the borrowing that will not go away when growth returns – over a five-year horizon. The OBR says that the structural deficit will turn into a slim structural surplus of 0.1 per cent of GDP in 2016-17, a year earlier than the mandate requires.

This surprisingly rosy prognosis can be attributed to the OBR being kind to the Chancellor in its estimate of the amount of slack in the economy. Robert Chote and his colleagues see a larger "output gap" than they did in December, meaning they think there is more scope for the economy and tax revenues to bounce back when the recovery finally gets going.

In December, it saw the output gap peaking at 3.5 per cent later this year. Now it sees a peak of 3.8 per cent in the second half of 2013. If the OBR had decided that the output gap had shrunk – something that a mechanistic reading of its own published models would imply – then it would probably have ruled that the Chancellor was not on course to hit his deficit reduction target, forcing him to pencil in still more cuts for the next Parliament.

There was another way in which the OBR was kind to the Chancellor. Mr Osborne boasted in the Commons – just as he did in December that the deficit was projected to fall in the present financial year even if one takes into account all the various one-off factors that flatter the public borrowing figures such as the Royal Mail and payments from the Bank of England's quantitative easing scheme. But there was another one-off boost to the public finances that the OBR noted in the small print of its dense report. It noted that £2.3bn in profits that the Bank of England had made on its special liquidity scheme – which was set up to help banks at the height of the global financial crisis – had been counted as tax receipts by the Treasury in the present financial year.

Stripping these profits out of the deficit figures reveals that borrowing is set to rise, rather than fall in 2012-13, peaking at £123.2bn. The OBR, however, made clear that it thinks the deficit will be broadly unchanged over this year and also 2013-14, pointing out that on average the borrowing forecasts at Budget-time turn out to be around £5bn out in any case.

But in other ways, the OBR has been less kind to the Chancellor. The second part of the Chancellor's original fiscal mandate was to have the national debt peaking in 2014-15. In December, the OBR said that Mr Osborne was going to miss this and that the debt pile would not peak until 2016-17. And the OBR had more bad news, saying that the national debt would not peak until 2017-18. Public sector net debt is now projected to peak at 85 per cent of GDP before commencing a gradual decline.

However, Mr Osborne, once again, said that he would not cut further in an attempt to hit this target. This decision to wave goodbye to one of his golden rules in December was one of the reasons why the credit agency Moody's stripped the UK of its AAA credit rating last month.

Now all eyes will switch to the other two large agencies, Standard & Poor's and Fitch, which also have Britain on negative outlook.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments