Remarriage to the EU? Macron plan is more of a Euro-cuddle

Sean O’Grady asks if the ‘onion’ model for European expansion will end in tears

After Keir Starmer’s mini-world tour and summit with Emmanuel Macron, there is much talk about the UK resetting its relationship with the EU. Labour has a pro-EU stance and the public mood is increasingly disillusioned about Brexit. Both Leavers and Remainers have reasons to be disappointed with the deal Boris Johnson negotiated to “get Brexit done”. On the other hand, no party – not even the Liberal Democrats – wants to turn the next election into another argument about Europe. Still, options for a closer relationship are floating around and a formal review of the Brexit deal is due to begin in 2025.

What does Starmer want?

It’s hard to be precise about that. He wants to protect his negotiating position, weak as it is, so we may never actually know until any deals are done (at which point he’ll declare them a triumph no matter how much he’s given away). He certainly doesn’t want to rejoin the EU or its single market or customs union, because it would reopen old wounds about Brexit. He is also reportedly hostile to EU “associate member” status, for similar reasons. The usual examples quoted are Norway and Switzerland, but those nations accept the customs union (Norway) or parts of the single market (Switzerland) or the visa-free Schengen area (both).

Beyond that, we know he’d like a deal on: veterinary and sanitary checks on livestock and fresh foodstuffs; some kind of migrant “returns” arrangement; access to EU markets for UK professional services; closer liaison on defence and security; and will continue to try and refine the rules around Northern Ireland and passenger movements. It would be a bespoke arrangement and a low-key series of incremental moves, no doubt dubbed “rejoining by stealth” in Europhobic circles.

In reality, Starmer would continue the Sunak policy of gradual, pragmatic, piecemeal mini-deals. A formal scheduled review of the existing EU-UK Trade and Cooperation Agreement is due in late 2025-26. That’s supposed to be a technical review, not a whole new treaty. If anything more radical were to be attempted, then questions about UK contributions to the EU budget, fishing quotas and the European Court would make an unwelcome return to British domestic politics. They would still be unpopular.

What is the EU offering?

The plan – under various names and nicknames, “the EU onion”, “inner” and “outer” circles, “variable geometry”, a reborn “European Political Community” (EPC) – is driven largely by President Macron; it sees a core Europe, with other nations, both inside and outside the EU, orbiting a Franco-German dominated-axis. The tight inner group would be dedicated to full integration and closer political union. Outside them might be the more sceptical EU members, often with existing euro opt-outs or grievances with the EU Commission - such as Denmark, Poland, Hungary and Italy. Then there’s an outer penumbra of the old European Free Trade Area (Norway, Liechtenstein, Iceland and Switzerland). Beyond that are aspirant members such as Serbia and the UK.

Such a system would be asymmetric and complicated. Ireland, for example, is fully committed to everything European but remains neutral and isn’t in the Schengen Zone. Britain might find itself inside an EU defence community while Malta and Hungary wouldn’t, though they both use the euro. The advantage would be that the “core” EU (Germany, France, Belgium, Luxembourg, Portugal, Spain and the smaller Mediterranean and East European nations) could proceed to becoming a federal state relatively rapidly, without much acrimony. That would also be a group in which France and Germany would be the dominant players. Traditional trade and economic benefits would still extend across the continent encompassing the existing EU plus various associate members; and a defence community could also welcome the UK, the other nuclear power in Europe.

We’ve been here before, haven’t we?

A British premier promising to renegotiate a deal with the EU in order to better suit Britain? Yes, many times. Cherry-picking and cakeism have been the plan for decades.

The first attempt at renegotiation came in 1974, a little more than a year after the UK joined the bloc. Labour prime minister, Harold Wilson, promised a “fundamental renegotiation” of the terms of entry agreed by the Heath government in 1972 and threatened the European Economic Community (EEC) with a referendum on withdrawal if he didn’t get his way; they probably knew he was bluffing. Protection for the Commonwealth and reform of the Common Agricultural Policy were two of the declared priorities. In the end, Wilson and his foreign secretary, James Callaghan, came away with comparatively little, backed EEC membership during the 1975 referendum, and won.

Four decades after Wilson’s doomed mission, David Cameron tried to pull off the same trick. He overpromised and came back from Europe with a deal that was widely derided; its most significant gains were a revision of the commitment to “ever closer union” and an emergency brake on migration. Unlike Wilson, Cameron went on to lose the 2016 referendum.

By contrast, Tony Blair and Gordon Brown quietly went along with the Lisbon and Nice treaties in the 2000s, content to dismiss them as minor affairs with no need for endorsement in a referendum.

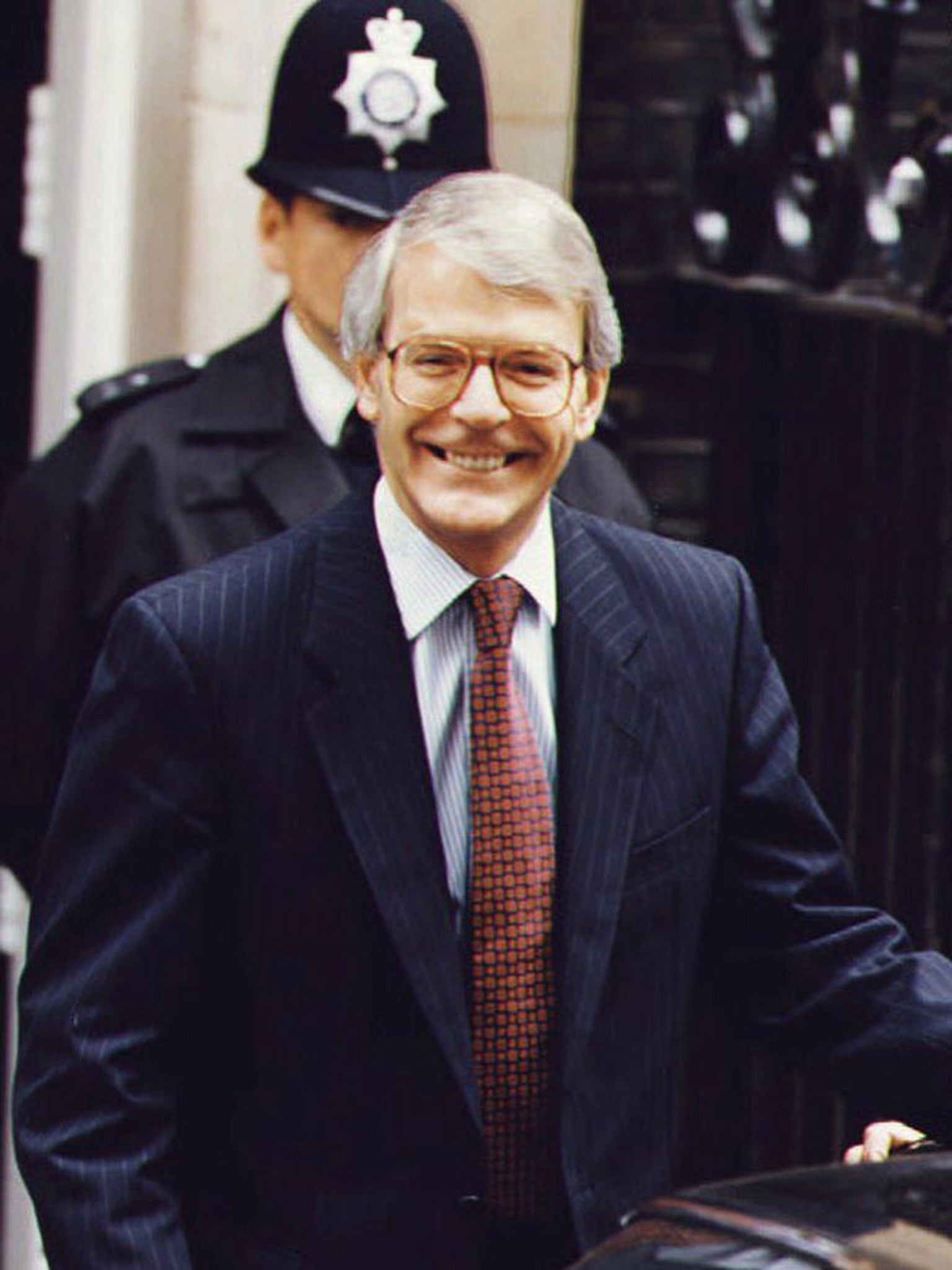

The most successful renegotiation was the skilful deal John Major and Douglas Hurd secured over the Maastricht Treaty (1992), with its opt-outs on the euro, the social chapter and charter of fundamental rights. Wisely, Major didn’t seek to put it to a referendum – and only narrowly carried it through parliament owing to his slim majority.

But Maastricht was an EU-wide initiative, rather than a unilateral attempt by the British to secure better terms. The only obvious instance of that happening was the historic EU budget rebate won by Margaret Thatcher in 1984; Brussels was “handbagged” for the first and last time. When Theresa May and Boris Johnson came to negotiate the Brexit treaty, they were so politically weak or desperate for a deal that they got what the EU wanted to give, albeit in different flavours. May chose one of the options proposed by chief EU negotiator Michel Barnier; Johnson ended up plumping for another. Unlike their predecessors, they could no longer threaten a UK withdrawal; the dynamics that gave us the May and Johnson deals remain.

The lesson of history therefore is that British prime ministers rarely achieve anything like success in such renegotiations. Sunak’s Windsor Framework (replacing the Northern Ireland Protocol) and Horizon deal, limited but useful, would be the models Starmer will try to follow.

When will Britain rejoin the EU?

On the British side, only when the lived experience of Brexit is so obviously harming the nation and its standard of living that rejoining looks unavoidable as an alternative to inexorable decline. That mood, after all, was how the UK came to seek membership in the first place, in 1961. The British people would need to be ready for another acrimonious debate or referendum. The terms of entry might well be less advantageous than the arrangements left behind in 2016, and the EU might be even more federalist.

Starmer is right to be wary of reigniting the Brexit debate, but Brexit is not as popular as it was. Given the manifest failure of Brexit to live up to expectations, being more friendly to Europe is something to which voters will respond. A Euro-cuddle, rather than remarriage, seems about the right approach for now. The election after next might see Stamer seek a second term and a mandate to negotiate terms of entry to, perhaps the single market. On this plan, Britain would reenter the EU in about 2036, two decades after the Brexit referendum.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments