Brexit timeline: Flashpoints from the 2016 referendum to leaving the EU in 2020

Ashley Cowburn unpacks the biggest political earthquake in decades and the Commons drama that followed

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Three and a half years after the British public voted to leave the European Union, the UK will formally leave the bloc on Friday.

Here The Independent looks back at the last few years of political turmoil and parliamentary logjam, as the UK prepares to end its 47-year membership of the EU.

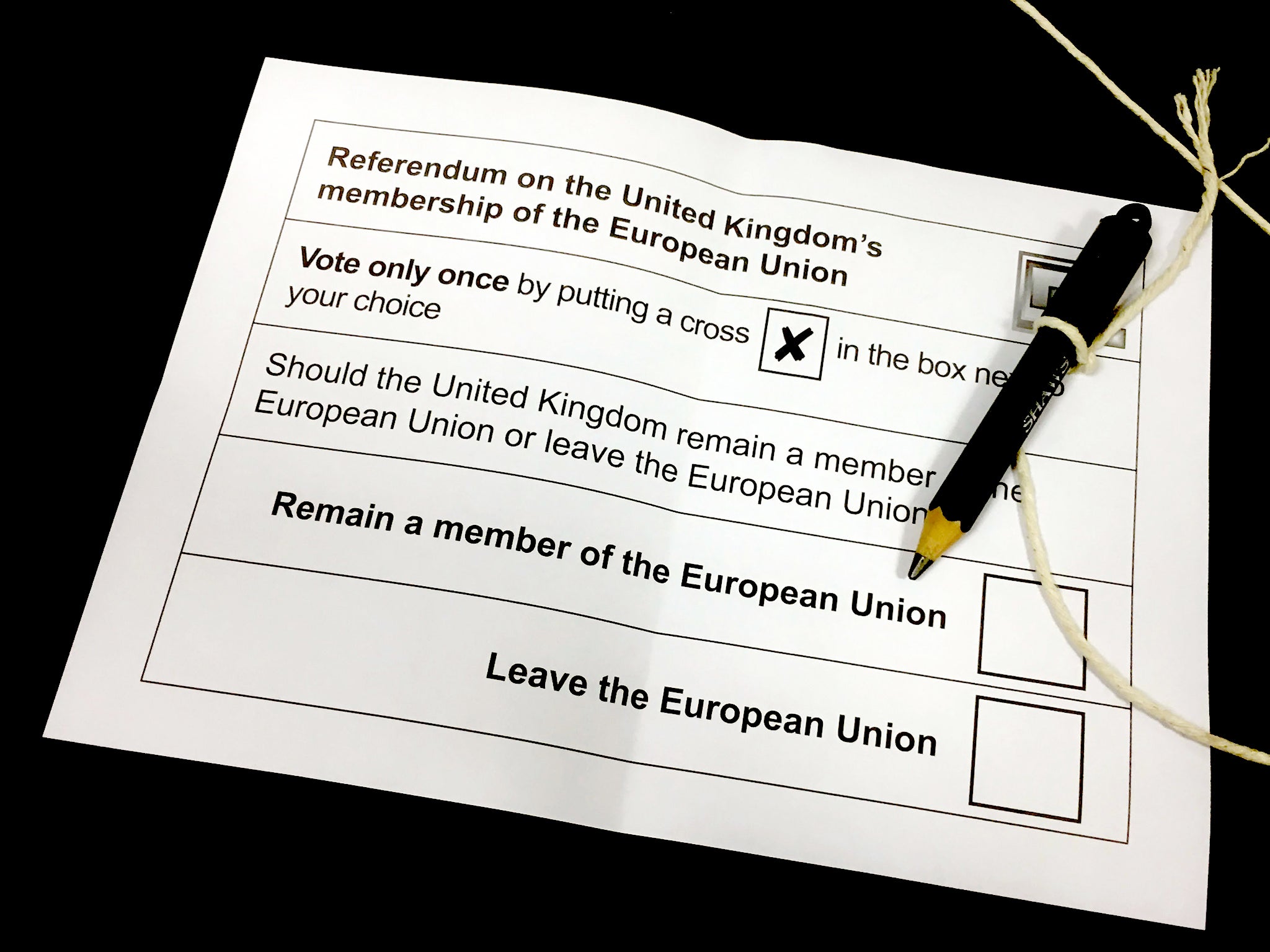

June 2016: Brexit referendum

In the biggest political earthquake for decades, Britain voted to leave the European Union by 52 to 48 per cent, forcing David Cameron to resign as prime minister on the morning of the 24 June. Speaking outside Downing Street he said “fresh leadership” was required to take the country forward in a new direction.

The Tory leadership contest kicked off days later, and within days Boris Johnson unexpectedly ruled himself out of the contest, after his close ally, Michael Gove, said he did not believe he had what it takes to be prime minister.

Civil war also erupted in the Labour Party, with Jeremy Corbyn facing a mass resignation of members of his shadow cabinet.

July 2016: Theresa May enters Downing Street

The race to lead the Conservatives was narrowed down to just two candidates in July, but after an incendiary interview, Andrea Leadsom dropped out of the contest. Shortly after, Theresa May entered No 10 for the first time as prime minister to take on the colossal task of severing the UK’s ties with the EU.

In September, Corbyn also emerged victorious after a revolt triggered a leadership contest. He won an even greater mandate from the Labour membership than in his first victory in 2015, securing his position.

October 2016: Conservative conference

After months of not revealing any detail of her “Brexit means Brexit” strategy, the prime minister outlined to delegates at the Conservative Party conference in Birmingham her red lines. She said the UK would leave the jurisdiction of the European Court of Justice, and signalled her intention to leave the single market.

November 2016: Government defeat at Supreme Court

May had argued the referendum meant that MPs did not need to vote on invoking Article 50, the process that would trigger the two-year negotiating period to broker a withdrawal agreement between London and Brussels.

But Gina Miller, the pro-EU campaigner, won her bid at the Supreme Court, which argued that only MPs had the power to trigger the mechanism, which would begin formal talks with the bloc.

January 2017: Lancaster House

In one of her biggest speeches as prime minister, May made clear she wanted to leave the single market and the customs union, and rejected existing models of membership used by countries such as Norway. Reacting to the speech, the Daily Mail’s front page headline the following morning hailed: “Steel Of The New Iron Lady”.

March 2017: May triggers Article 50

After parliament voted to trigger Article 50 and kick off negotiations with the EU, Donald Tusk, the European council president, confirmed he had received notification from the British government to begin formal negotiations and implement the decision of the 2016 referendum. A deadline for talks to conclude was set for 29 March 2019.

April 2017: General election

Despite insisting there shouldn’t be an early general election, May shocked Westminster and made the greatest gamble of her political career. Explaining her decision outside No 10, the prime minister said other MPs and peers were attempting to derail her negotiations with Brussels. “The country is coming together, but Westminster is not,” she said.

It ultimately ended in disaster, and in June, the Tories’ slim majority in the House of Commons was wiped out, forcing May to establish a minority government by striking a supply and confidence agreement with the DUP. It set the stage for two years of fraught parliamentary votes and debates on the UK’s relationship with the EU.

December 2017: Brexit phase two

After torturous negotiations with Brussels, an embattled May unveiled a “joint agreement” with the bloc after Jean-Claude Juncker, the European Commission president, said “sufficient progress” had been made on all three of the “divorce issues”, including the Irish border, a financial settlement, and EU citizens’ rights. This was when the so-called backstop reared its head.

Summer 2018: Chequers

In June 2018, the House of Commons passed the government’s EU Withdrawal Bill, enabling EU law to be transferred into UK law after Brexit. But a crucial amendment was added to the legislation in the winter months, giving parliament a “meaningful vote” on the final deal.

A marathon session of the cabinet was held in July at the prime minister’s Chequers residence. Ministers approved May’s Brexit plans and aims for a future relationship, including the creation of a new UK-EU free trade area for goods. But in protest at the agreement, both the Brexit secretary, David Davis, and foreign secretary, Boris Johnson, quit the cabinet.

Johnson – after releasing to the press a photograph of himself signing his resignation letter – said the prime minister’s plans mean “we are truly headed for the status of colony” of the EU.

November 2018: Brexit deal reached with Brussels

Brussels and London agreed the draft text of a Brexit agreement – a landmark moment – and May summoned her cabinet to discuss the contents of the text. But her government was thrown into further turmoil after the new Brexit secretary, Dominic Raab, and the work and pensions secretary, Esther McVey, quit their cabinet roles, claiming the agreement failed to honour the result of the referendum.

December 2018: Confidence vote

In the face of considerable opposition to her plans in the House of Commons, the prime minister pulled a critical vote on her Brexit deal.

Jeremy Corbyn branded it a “desperate step”, adding: “We have known for at least two weeks that Theresa May’s worst-of-all-worlds deal was going to be rejected by parliament because it is damaging for Britain.”

Two days later, the Conservative Party held a secret confidence ballot in May’s leadership. But she won the vote by 200 to 117, allowing her to remain in post.

January 2019: Meaningful vote No 1

The first meaningful vote was finally held on the Brexit deal in January 2019 and became the biggest parliamentary defeat in British political history, as MPs rejected the agreement by a resounding majority of 230.

Corbyn tabled a vote of a confidence in May’s government, which she survived by 325 to 306 votes.

March 2019: Meaningful Vote (continued)

The House of Commons rejected the government’s Brexit deal a second time at the beginning of March, and the prime minister was forced to seek an extension from the EU until 30 June. She described it as a “matter of great personal regret”.

On the day Brexit was originally meant to be delivered – 29 March 2019 – MPs again rejected the withdrawal agreement by 344 votes to 286, a majority of 58. A round of “indicative votes” was held and MPs rejected every option.

Spring 2019: Extension

EU leaders agreed a second “flexible extension” to the Brexit process until 31 October after the first short extension to the negotiating period expired on 12 April. After angering many Tory MPs, talks between the government and Corbyn’s Labour Party ended without an agreement.

On 24 May, May announced outside Downing Street she would stand aside as prime minister and leader of the Conservative Party.

“I will shortly leave the job it has been the honour of my life to hold,” she said. “The second female prime minister, but certainly not the last. I do so with no ill will, but with enormous and enduring gratitude to have served the country I love.”

July 2019: Conservative leadership contest (round two)

May left No 10 for the last time in July, at the climax of the Tory party leadership contest. Boris Johnson defeated his rival, Jeremy Hunt, in a ballot of Conservative members and promised to deliver Brexit by 31 October, “no ifs, no buts”. He said he was “convinced we can do a deal” to resolve the issue of the Irish border but he would prepare for a no-deal Brexit.

September 2019: Prorogation

The Queen was dragged into an extraordinary row over Brexit, as the new prime minister requested the suspension of parliament for a five-week period. The Labour leader said Johnson’s plan to prorogue was “an outrage and a threat to our democracy”. The monarch, acting on the advice of her ministers, approved the order to suspend parliament no earlier than 9 September and no later than 12 September.

In response, MPs acted with haste to push through the Benn Act, which aimed to force the government to request a Brexit extension if no deal was in place by mid-October – avoiding a no-deal scenario. More than 20 rebel Tories, including former chancellors Philip Hammond and Kenneth Clarke, lost the party whip.

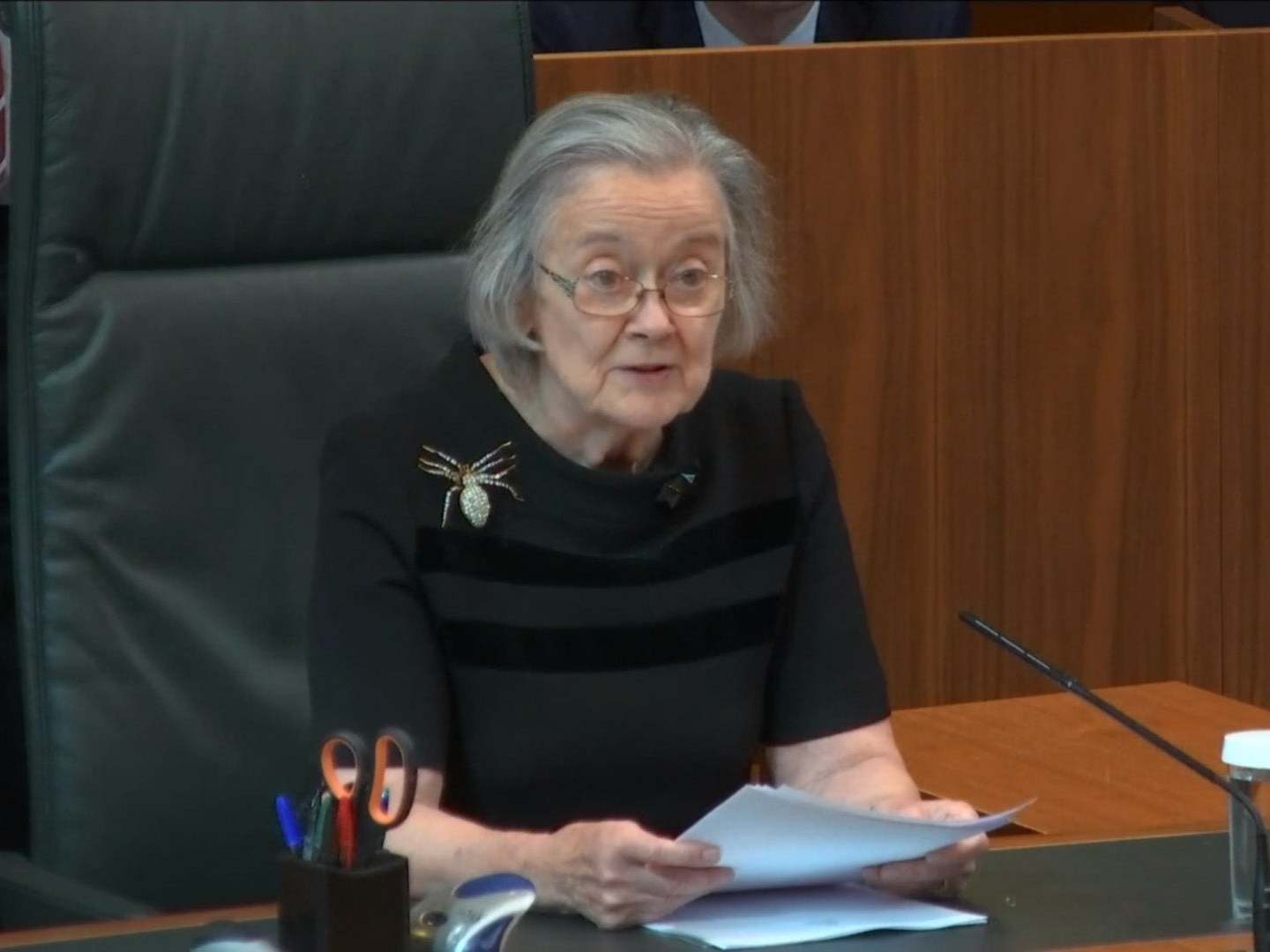

Towards the end of the month, the Supreme Court said Johnson’s prorogation of parliament was unlawful in an explosive ruling, effectively ending the closure of parliament. The court’s president, Lady Hale, said the suspension had the effect of frustrating parliament and was “void and of no effect”.

October 2019: New deal

Johnson put forward his formal Brexit plan to the EU, revealing his blueprint to solve the Irish border issue, but the European Commission president, Jean-Claude Juncker, said there were “still problematic points”.

Two weeks later, the prime minister announced the UK had reached a “great deal” with the EU that meant that “the UK can come out of the EU as one United Kingdom – England, Scotland, Wales, Northern Ireland, together”.

But the DUP said it cannot support the deal in parliament, citing a series of objections over the integrity of the union and Northern Ireland’s economy.

The legislation was agreed in principle in the House of Commons, but MPs rejected Johnson’s attempt to ram it through the Commons. He was forced to request another Brexit extension until 31 January.

After several attempts, and a last-minute offer from the SNP and Liberal Democrats, Labour finally backed Johnson’s request for an early general election.

December 2019: Election reckoning

Having campaigned on a promise to “get Brexit done”, Johnson secured a landslide win at the election and with a comfortable 80-seat majority was able to command the Commons in a way May never could. Labour suffered its worst election result since 1935, forcing Corbyn to outline his resignation timetable and kicking off a leadership contest in the party.

January 2020: Brexit Day

After the decisive general election victory, Johnson’s Brexit withdrawal agreement cleared all its parliamentary hurdles in both the Commons and the Lords, becoming law. The European parliament ratified the deal on 29 January.

At 11pm on Friday 31 January, Britain will leave the European Union. The UK will enter the “transition period” and begin negotiations with the bloc over a future trading relationship. The saga is far from over.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments