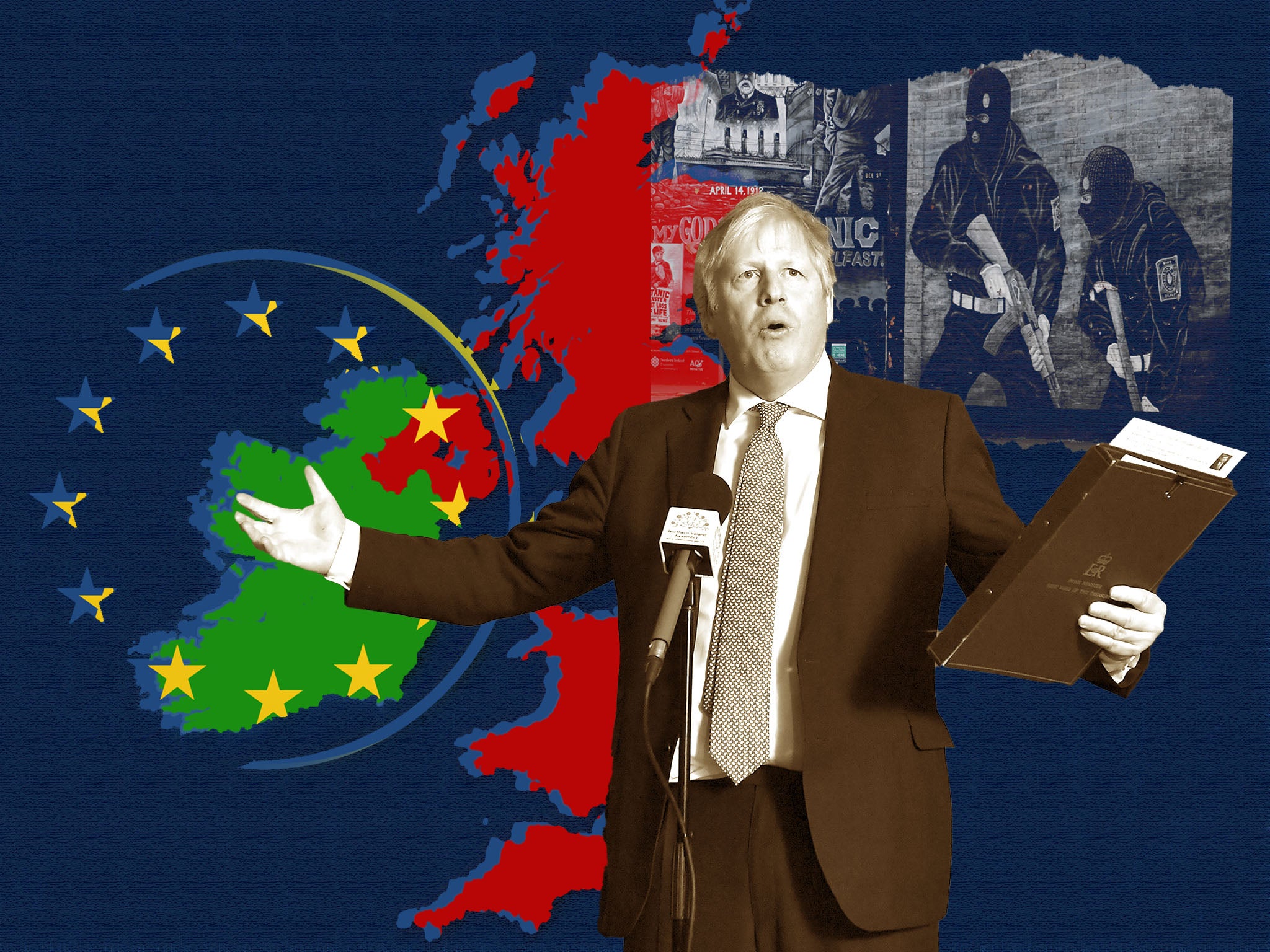

How Boris Johnson – and Brexit – almost unravelled the Good Friday Agreement

The former prime minister’s reckless suggestion that the Irish border would not be a problem as he sought to ‘get Brexit done’ came close to causing irreparable damage, writes Sean O’Grady

Interesting fact as we reach the 25th anniversary of the Good Friday Agreement: there is no actual reference to a “hard border” or “soft border”, or anything like that, to be found in the famous text.

It is certainly a matter of hard political reality, though, that the GFA relies on there being no hard land-border between Ireland (ie the EU) and Northern Ireland (ie the UK). That is why we have a partial trade border down the Irish Sea between Great Britain and Northern Ireland instead.

The border had to go somewhere. If it was to be on the island of Ireland it would be unacceptable to nationalists and republicans, and most unionists.

But if it was plonked down the Irish Sea, then, as we see now, unionists will find it irksome, alienating and equally unacceptable. The origins of the present troubles, and the (thankfully still slight) risk of a return to the Troubles, lies in Brexit and its impact.

Reconciling Brexit with the Irish peace process is a frankly insoluble problem, like a Rubik’s Cube that someone has secretly sabotaged. The best you can do is to get it mostly right, which is where Rishi Sunak’s Windsor Framework is superior to Boris Johnson’s original Northern Ireland protocol.

But the protocol, with all its flaws, was what Johnson signed without understanding it, so the legend goes. Hence his culpability. Sunak’s Framework is flawed, but he’s got a lot further than Johnson ever did. That’s because he was bothered about Northern Ireland in a way Johnson never seemed to be.

So, if you want to rely on the GFA as a sort of latter-day holy writ to sustain some argument or other, then you will not find it in the original document. What you have instead is the adamant and (mostly) sincere commitment from virtually everyone involved that a hard border is simply unacceptable.

It is, by dint of constant repetition by successive taoiseachs, British prime ministers, leaders of all the Northern Ireland mainstream parties and even Eurosceptics, a political imperative, an obligation.

Some of the more insouciant Brexiteers sometimes suggest that the British could just refuse to put a border up anywhere. The attitude is that if the EU insists on one, they can have one in Ireland, but that’s their business.

However, as well as being puerile and insensitive, that’s against World Trade Organisation rules; and policing a curly 515km- (320 miles) land border is impractical. Brexit is in any case a problem of British creation.

The problem that has always been nascent, and became distressingly real, is that the GFA, and with it the imperceptible border, power sharing and peace, is simply incompatible with Brexit.

It is the UK leaving the EU that has brought this tension, and there is one man who bears a heavy degree of responsibility for the fact of Brexit and its implementation – and thus the undermining of the GFA to the point of near-destruction – Boris Johnson. It was his reckless and dangerous act of deception that the border wasn’t a problem, when it plainly was and is. It stands today as another regrettable, to say the least, legacy of his dismal premiership.

The reason why the border was never mentioned in the GFA, of course, is that back in 1998 everyone made the perfectly reasonable assumption that the UK and Ireland would continue to be member states of the European Union. It didn’t occur to anyone that a few in the Tory party, then almost moribund, could somehow get the UK out of its central international partnership, one which had delivered much prosperity. By coincidence, the year 1998 marked the 25th year of both countries’ EU membership.

One of the more overlooked but useful benefits of being in the same customs union and, latterly, single market, was that many of the usual border controls had become redundant and long disappeared across the EU, and in Ireland. In their place, however, came an ugly infrastructure of police and military forts and watchtowers.

The GFA swept all those hulking reminders of British rule away, and the new, practically invisible border on the island of Ireland was a huge factor in enticing Republicans to adopt peace and join, with fits and starts, the power-sharing assembly, then the executive and, now, to have their leader Michelle O’Neill chosen by the people as the first minister-elect of the province.

Despite the current Democratic Unionist Party boycott and the drumbeat of a return to violence, that is a remarkable journey. Hence the cautious celebrations attended by the King, President Biden and others.

Still, 800 years of history tell us that there’s no room for complacency for anyone contemplating peace in Ireland, and it’s worth contemplating exactly why Northern Ireland finds itself being menaced by the forces of nihilistic violence again.

Brexit is indeed the underlying cause. One original sin, still too often forgotten, is that “Ulster says Remain” to borrow a phrase, but was ignored. In the 2016 referendum Northern Ireland voted by 56 per cent to 44 per cent to stay in the EU. Four of the five main parties in Northern Ireland – the Ulster Unionists, Alliance, the SDLP and Sinn Fein campaigned for Remain. Only the Democratic Unionist Party, wary of any dilution of their British identity via the EU, wanted out.

Yet the erroneous impression persists that the DUP speaks for the whole of the people of the province and the unionist community. This is partly down to Sinn Fein’s absence at Westminster, and the absence of Alliance and SDLP MPs at Westminster during the crucial debates and votes between 2017 and 2019.

It was also because Sinn Fein had collapsed the institutions over the role then-first minister Arlene Foster had played in a disastrous green energy scheme, so there was no devolved administration to speak up for the province. For much of the time, the extreme positions the DUP adopted gained and outsized influence, which Boris Johnson encouraged, but then betrayed. It was even by his standards, dishonourable conduct.

Johnson once posed as the staunchest ally of the unionist community. This has only served to add to the general suspicion of Westminster among Northern Ireland politicians. Johnson resigned as foreign secretary in Theresa May’s government in 2018. She had worked hard to craft the Chequers Agreement, which minimised the extent of border frictions by keeping the UK in the EU customs union and parts of the single market, with a special status for Northern Ireland – but no hated border in the Irish Sea.

Johnson rejected it, and offered instead a typical piece of cakeist fantasy in his resignation statement: “With goodwill and common sense, we can address concerns about the Northern Irish border and all other borders.” That was the sum total of his policy; goodwill, and the typical Johnsonian idea that if we just ignore it, the issue will evaporate of its own accord.

Once liberated from collective responsibility he continued to ingratiate himself with the DUP and their allies in the Tory party – promising the impossible just as he did in the EU referendum, and with the same insincerity and purely selfish motivations.

In 2018, when May was still trying to get her deal through the Commons, he even travelled to the DUP conference in Belfast to tell jokes about the Titanic and to warn them about the perils of May’s doomed deal: “If we wanted to do free-trade deals, if we wanted to cut tariffs or vary our regulation then we would have to leave Northern Ireland behind as an economic semi-colony of the EU and we would be damaging the fabric of the union with regulatory checks and even customs controls between GB and NI – on top of those extra regulatory checks down the Irish Sea that are already envisaged in the Withdrawal Agreement.

“No British Conservative government could or should sign up to anything of the kind and so our answer at the moment is rather desperately to make sure the whole UK stays in the backstop with the EU having the power to decide whether or not we can ever leave and why should they?”

Yet a little more a year later, Johnson was ready to do precisely what he had accused May of doing, and sell out the Unionists by agreeing to the Northern Ireland protocol as part of his UK-EU Withdrawal Agreement.

It was a dramatic U-turn, and it would in time come to jeopardise peace in Ireland; but the charm of it for Johnson was that it wouldn’t come into actual effect for many months, way after the 2019 election, at which point he’d have his own large Commons majority and the DUP and their more loyal Eurosceptic friends could do nothing about the fait accompli. It was the biggest case of political misselling in modern history – but the cakeist delusion could not last forever.

Thus, in November 2019, the election out of the way and his 80-seat majority secured, Johnson was still telling worried Northern Ireland businesses they could put customs declarations forms “in the bin” because there will be “no barriers of any kind” to trade crossing the Irish Sea. As late as August 2020, Johnson was still telling anyone who’d listen that: “There will be no border down the Irish Sea – over my dead body.”

Even though that was precisely and obviously what was being implemented, with new customs facilities being built and EU officials stationed at the port of Larne. It was one of his more extravagant exercises in political dishonesty.

When, late in his premiership, he found that he could no longer pretend there was no problem, and the DUP had collapsed the Stormont administration, Johnson published a bill that would, in the words of the then-Northern Ireland secretary, Brandon Lewis, break international law “in a very specific and limited way”. It infuriated the EU, and the mild-mannered Irish foreign minister, Simon Coveney, told the Dail, the lower house of parliament: “It is surely not too much to ask for the UK to implement the withdrawal agreement which it agreed to.”

Johnson’s gamble poisoned relations with Ireland and the EU still further; the evidence suggests that there was never any serious intent to use it, because it would have invited retaliatory tariffs to be slapped on UK exports to the bloc.

Paused in parliament, it survived Liz Truss’s brief premiership before being quietly jettisoned by Rishi Sunak. To be replaced by the Windsor Framework. In a quixotic and highly hypocritical gesture, Johnson (and Truss) joined a revolt of Eurosceptics against the Framework; it flopped and the rebels numbered all of 22.

The most galling aspect of Johnson’s attitude to Northern Ireland is the private contempt in which he seems to have held the interests of the province, in sharp contrast to his Churchillian public pronouncements.

In June 2018, for instance, at a private function organised by the Thatcherite think-tank, Conservative Way Forward, Johnson’s frustrations spilled over in remarks that were later leaked: “It’s so small and there are so few firms that actually use that border regularly, it’s just beyond belief that we’re allowing the tail to wag the dog in this way. We’re allowing the whole of our agenda to be dictated by this folly.”

According to a memoir written by Gavin Barwell, May’s chief of staff, in his internal cabinet discussions, Johnson regarded the Northern Ireland issue as a “gnat”, and May’s elaborate safeguards for the GFA as “mumbo jumbo”. So much for the “passionately unionist” Johnson.

Northern Ireland didn’t figure much in the debate on Brexit in the rest of the UK in 2016, but it should have done. Like other Brexiteers, Theresa Villiers, the Northern Ireland secretary at the time, expressed a breezy confidence that there’d be no real problems – and it’s all too plausible to suppose that Johnson devoted even less effort than did Villiers to seriously thinking through the consequences of Brexit on this corner of the union (or, indeed, its equally malign impact on Scotland and its place in the UK).

It cannot, however, be said that there were no warnings. Back in 2016 John Major and Tony Blair, who helped keep the peace process alive in the 1990s, spoke out in a joint intervention. Major warned the union would be weakened, and Blair’s words were even more portentous.

He declared, seven years ago, that it would be “profoundly foolish to risk those foundations of stability” created by the GFA. He added: “I say, don’t take a punt on these people. Don’t let them take risks with Northern Ireland’s future. Don’t let them undermine our United Kingdom.”

He knew, and we know, exactly who he was referring to. He was right.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments