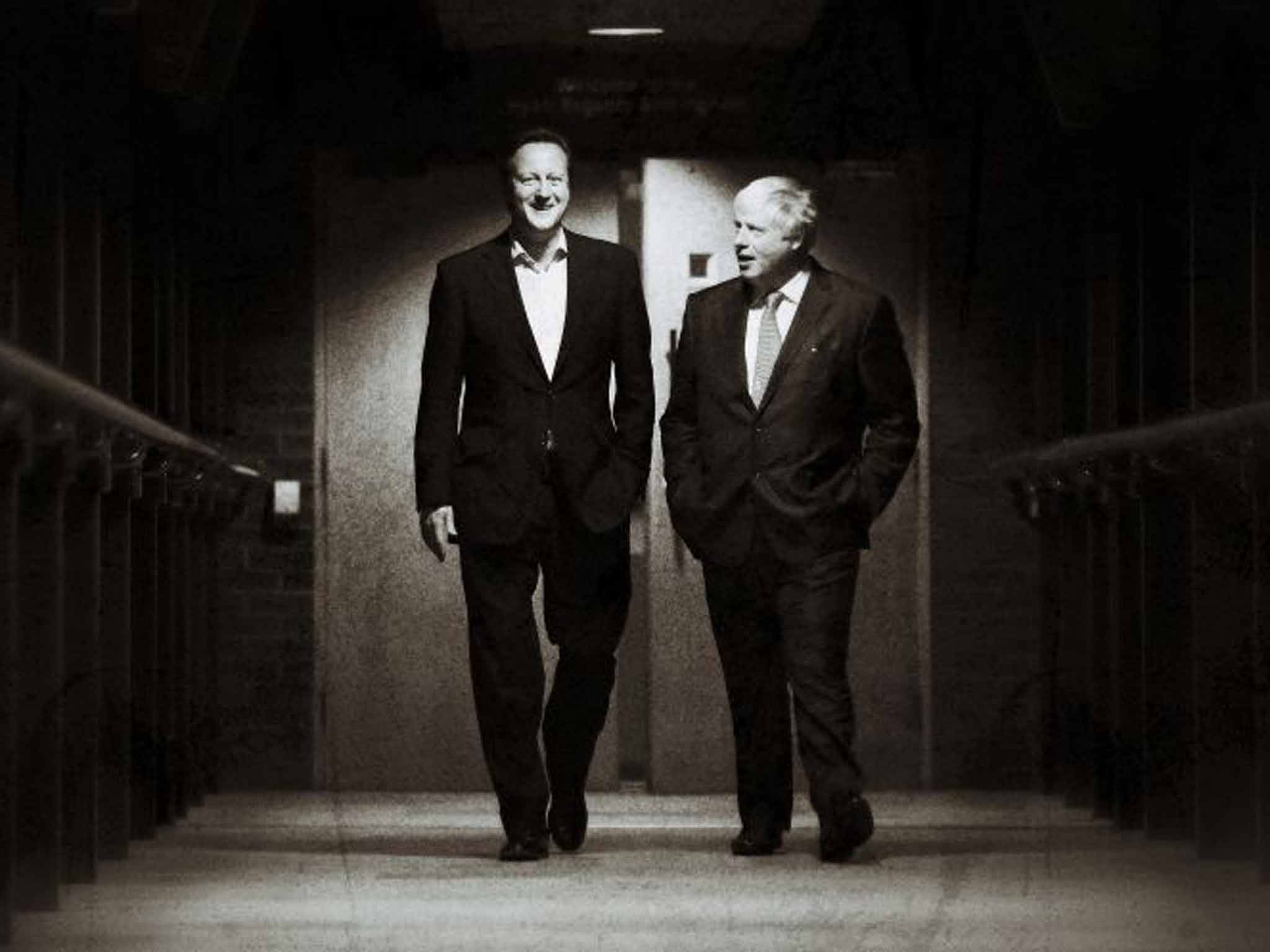

Boris Johnson and David Cameron: How a rivalry that began at Eton spilled out on to the main stage of British politics

As Boris makes his bid for Brexit (and, not long after, No 10 too), his biographer Sonia Purnell traces how a feud came to the crunch.

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.A visitor from Mars might well have been baffled by the obsession of the TV news bulletins last Sunday evening with two almost identical black-painted front doors. One, a number 20, had Boris Johnson emerging from it, dressed in a prime ministerial costume of dark suit and clean white shirt, to address one of the best orchestrated “spontaneous” media scrums for years. The other, a certain No 10, had no one coming in or out, and apparently no one eagerly waiting outside it. The message was clear – Brexit Boris was firing the opening salvo in what threatens to become a very nasty Tory civil war. All so carefully stage-managed for maximum visual contrast, it hardly mattered that his spoken words were still bumbling, self-contradictory and hardly the sort of rousing call to arms you might expect.

Anyone with residual doubts about Johnson's desire to expel Cameron from the premiership could hardly fail to have read the signals. Here was the would-be hugely popular new PM (of a free and reinvigorated Britain) just waiting for battle to begin!

Meanwhile, across town behind the Downing Street curtains, Johnson's long-time rival (but no, never friend), was in danger of being cast as the general in desperate search of some troops. Dave's New Deal with Europe, for all the clean shirts and countless packets of Haribo sweets that Cameron had invested in it, was never going to be able to compete in media terms with Boris's box-office bugle. The pervading silence was heavy with bitter intent.

So yes, what a triumph for Johnson: proven master of the media; political player of unparalleled popular power; man of conscience (or so he claimed to the assembled reporters while looking hastily at his shoes) over career.

Indeed, apparently so taken was the Mayor of London with the selflessness of his high-drama decision to back the Leave the EU campaign, that he seemed temporarily to have forgotten the name of his prime minister. That was not the only personal slight he delivered to his fellow Old Etonian that day. We are told that he informed “Dave”, as Johnson crushingly likes to call him, of his decision to join the Outers gang by text only nine minutes before he told the rest of the world. Courtesy has never been Johnson's strong point.

Can we really blame Cameron therefore when he launched into Boris on Monday in a dramatic session in the Commons? Finally, he could say – in public – what he no doubt has for so long been thinking in private: that the mayor was putting Boris before Britain and that some of his ideas, notably the flaky one about winning a better deal in a second referendum, were “for the birds”. At least there was a new honesty in the air when Johnson shouted “rubbish, rubbish!” from the back benches. But when two Tory Old Etonians go to war, eloquence does appear to be one of the first casualties.

The real world beyond the excitable Westminster media cadre seems to have been less impressed with Johnsonian showmanship. Monday morning, freaked by the idea that the Mayor of London really might gamble with the future of his city's financial prosperity for the sake of personal ambition, the markets cut sterling to levels not seen for nearly seven years. That blow to national interests is not likely to have impinged significantly (if at all) on Johnson's focus on the Downing Street prize he has desired with every fibre of his being for so long. He knows that, in all probability, this running for the Brexit door represents his last and best chance of achieving his goal.

In private and often in public, at least until a few days ago, Johnson voices great sympathy for the European project and its underlying aims of greater peace and prosperity. He has been known to defend the EU and its protagonists compellingly when others attack it. I have heard him do so myself. His family is inextricably linked with the Commission and the Parliament – indeed his father Stanley worked for the former and was a member of the latter and draws a handsome EU pension. Johnson was educated in Brussels, courted his second wife Marina there, and his eldest daughter Lara was born in one of its hospitals. He speaks French, Spanish, Italian and German far better than he would dare let on in the presence of another Englishman. “The trouble is I'm not an Outer,” he said himself, only a month or so ago.

And yet, clearly the scenario of Cameron's political demise following an Out vote in June, followed by his own swift and triumphant coronation as Tory leader and prime minister was just too much to resist. Just last week, special forces were sent out to test the waters in the form of his fiercely Europhile Marina – who once told me she personally cornered the proprietor of the Daily Mail to berate him over his paper's unfair and inaccurate reporting on the EU. Marina wrote an essay apparently attacking Dave's Deal for being politically expedient but in legalistic terms entirely ducking the red card issue of the erosion of sovereignty. Needless to say, her words featured prominently in the newspaper she had once so fiercely scorned.

With Johnson himself, any such private European beliefs have always been outweighed by his own blond ambition. Back in the 1990s, when I worked with him for The Daily Telegraph in Brussels, he was making his name by writing excoriating and highly creative Eurosceptic copy about the Commission supposedly banning prawn cocktail-flavoured crisps or making fishermen wear hairnets. As the then EU correspondent for this newspaper, David Usborne, remarked on Johnson's perennial drive for the main prize: “He compromised his intellectual integrity to get on,” adding that Johnson knew all too well that he was “writing out of his ass”. Others, less polite, described Johnson's work in Brussels as “lying and conniving”.

The man himself once admitted that he had merely spotted a “market opportunity” to make his name with such inventive stories when the consensus was broadly in favour of the European project. To write these explosive tracts took some formidable powers of re-invention from the then predominant Bumbling Boris, which were unleashed by what became known as the Four O'Clock Rant. During this daily deadline ritual, for which he would lock his office door to guarantee complete seclusion, he would proceed to hurl expletives at a ragged yucca plant on his desk for several minutes to work himself up into a requisite frenzy of focus and creativity. The shouting could be heard clearly on the street below. He admits that one hand still bears a scar where the force of his emotions snapped a Biro.

Another telling off-guard moment back then came when Johnson admitted he got a huge kick out of trying to change the course of history even if that would mean “throwing rocks into glasshouses and listening to the shattering of glass”. More recently, he subtitled his book The Churchill Factor (which contains 31 references to himself in the introduction alone and which resembles something of a personal manifesto rather than biography of another) with the words “How One Man Made History”.

Those who knew him well back in Brussels, would surely recognise some of the motives inherent in his actions now – as well as his absurdly grandiose fondness for comparing himself to Britain's greatest wartime leader (and fellow journalist, painter etc). He loves the feeling and excitement of power, without necessarily having any plans for what to do with it beyond his own advancement and pleasure.

Johnson has also, appropriately enough for a man accustomed to unfathomable good fortune, harboured a long-time fondness for a gamble. Again and again in his life, he has risked the wrath of his employers, his colleagues and, of course, Marina by privileging his own self-interest over theirs, and again and again he has got away with it. At Eton, Oxford, The Spectator, The Daily Telegraph, Henley, Uxbridge and the London mayoralty he has succeeded, without always investing the usually necessary effort and commitment. No doubt his calculation this time is that his undoubted genius for self-promotion will allow him to get away with this latest dicing with danger, too – after all, even his father Stanley has publicly acknowledged that if Britain votes In then his son has just made a career-ending decision.

Both Johnsons would be the first to appreciate the younger one's undoubted gifts for winning campaigns, proven twice against the odds in London mayoral elections. No doubt his expectations depend on that Borissian fairy dust turning votes in his direction this time, too. The bookies believe he has called it right – making him the new favourite for next Tory leader (replacing George Osborne, whose pennant is inextricably tied to the Remain mast) and cutting the odds for his success from 3/1 to 5/2. And some polls suggest Johnson could lure an extra 10 per cent to the Outer side.

But there are obvious questions. What exactly are his reasons for Brexit? (He has not spelt them out in any convincing detail beyond vague references to saving money and “taking back control”?) Is he really a genuine Outer when he's already talking about a second referendum to stay In? And what will his role be over the months leading up to the referendum to make that happen? Will he content himself with accusing the PM, as he has done this week from the safety of City Hall, of “scaremongering” and “wildly exaggerating” the potential downsides of Brexit? If so, by holding back, could he survive an In vote? Are we seeing yet another demonstration of Johnson's favourite policy, that of having his cake and eating it?

It is notable that he is spurning the idea of entering what he calls “blimming” debates or sharing platforms with fellow Outers. Nigel Farage and George Galloway would certainly not count as his comrades of choice – although it is difficult to name anyone who would. Michael Gove, the fellow Outer who dined with Johnson last week and would seem to be more in tune with him politically has, in truth, never trusted him or been his friend. Indeed, only a year ago, the Justice Secretary was branding Johnson as “unfit” to govern (an opinion, by the way, shared by the Court of Appeal).

In truth, Cameron is not the only colleague – politician or journalist – that Johnson has alienated over the years. His fellow Tory MP Sir Nicholas Soames (who helped Johnson with his best-selling book on his grandfather) effectively called him a liar on Twitter this week by saying he “really isn't an Outer by conviction”. The former MP Jerry Hayes simply branded him a “copper-bottomed, hypocritical little shit”.

They and many others have come to realise that Johnson is only really comfortable as a soloist. For all his apparently unscripted asides during his public speaking, he likes to be rigidly rehearsed before opening his mouth. Avoiding debates on such a momentous national question as to whether we should remain within the EU may save Johnson from the extempore pressures he dislikes, but it is also hardly prime ministerial. He has rarely performed well in the Commons, a bearpit where bumbling and long-winded attempts at humour fall flat.

Johnson has always believed that Cameron's job in Downing Street was rightly his; that he is cleverer, more original, more popular, more entitled to occupy the pinnacle of power in this country than the (in his view) undistinguished but super-privileged son of Berkshire who beat him to the top. Yes, the fact that Cameron was two years below him at Eton – a terrifically hierarchical school – rankles deeply. As does the fact that it was Boris who shone there, not Cameron. Masters recall Johnson as a remarkable teenager. They do not recall Cameron at all.

Of course this academic superiority was reversed at Oxford University, to Johnson's eternal disgust, when Dave scooped a First to Johnson's 2:1. “But only in PPE,” Johnson likes to scoff when teased on this subject, “rather than a real subject like Greats.”

Until now, Cameron and Johnson have pretended in public that they are “friends” who joke around and make helpful criticisms of each other, as “friends” do. Yet while Cameron might have been shocked by the scale and style of Johnson's betrayal he can hardly have been surprised. Sure, he has sat faithfully in the audience at Johnson's conference speeches every year, looking as if his cheeks were going to explode at the effort of grinning through barely veiled jokes and jibes at his expense. But then Cameron has long had to tolerate – at least in public – the disloyal antics of London's mayor because his popularity made him untouchable.

Now the gloves are off. Cameron owes Johnson nothing; he no longer needs to indulge the man he once called his star player. Time will tell who wins this contest, but it is possible that Cameron will survive to take his revenge.

Johnson is a figure of enormous gifts and talents. He has popularity, charm, brains, self-belief, charisma, sex appeal, wit, a talent for good luck and lashings of celebrity gold dust. He is probably the most complex and interesting public figure in Britain today and fascinates people across the globe. He could still do so much for his country, if he put his mind to it. But his decision – against his own natural instincts – to opt for Out is yet another example of where those who know him well believe he has gone for the self-serving rather then the principled. And for a man blessed with so much, that is a huge shame.

Sonia Purnell is the author of 'Just Boris: A Tale of Blond Ambition' (Aurum Press, £8.99)

The Rivals: When politics got personal

Blair vs Brown

The TB-GBs, as they were called, afflicted Labour for the entire Blair government, and for some time after. Entering parliament together as fellow modernisers, Brown was the senior partner, even teaching Blair how to write press releases and craft soundbites. They fell out after it became clear Blair would run for leader in 1994. A misunderstood pledge over dinner, Mandelson and Cherie fuelled the grudge.

Thatcher vs Heseltine

Long before Bojo, there were tales of blond ambition. Heseltine represented an older tradition of Toryism: pro-European, one- nation, socially concerned. The other, well, the opposite. But they shared a liking for power. Heseltine ended her time in Number 10; but the assassin did not seize the crown in 1990, and John Major – who had no rivals – stayed as PM for the next six years.

Gladstone vs Disraeli

This was perhaps the first feud to combine personal loathing with something that approximated to the modern party system. Liberal Gladstone stood for social reform, abstinence and Home Rule for Ireland; Tory Disraeli made Victoria Empress of India, made friends with the brewers and invented a type of working-class Toryism that was to prove remarkably resilient.

Jenkins vs Crosland

Although contemporaries, Crosland made the earlier progress as a top social democratic thinker, and was a kind of mentor to Jenkins. 'Woy', the more Asquithian of the two, was socially ambitious and inclined to anecdote above ideology. Public school and Oxford educated, both long coveted the Labour leadership, and premiership, but lost out in 1976 to Plymouth lad James Callaghan.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

1Comments