All change at world's oldest parliament

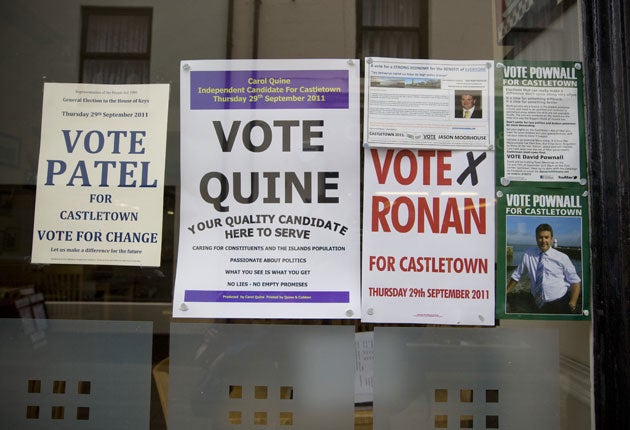

As the Isle of Man prepares to elect a new government, Kate Youde, who grew up there, takes soundings on the election trail

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Ask people what they think about the Isle of Man and frequently you will be bombarded with outdated stereotypes: that it is a "tax haven" nation of motorcycle nuts and floggers – actually, the last birching was in 1976 and the punishment is now consigned to history books – overrun with tailless Manx cats.

What they don't mention is that the small British island has long been at the forefront of democracy: it boasts in Tynwald, founded more than a thousand years ago, the oldest continuous parliament in the world.

There is more: in 1881, the Isle of Man became the first country in the world to give (propertied) women the vote in national parliamentary elections; in 2006, it was the first nation in Western Europe to introduce voting for under-18s, extending the right to 16- and 17-year-olds.

Yet the odds are that while British eyes are fixed on the Labour Party conference in Liverpool this week, few will notice islanders across the water returning to the polls to elect the 24 Members of the House of Keys (MHKs), the Manx equivalent of MPs.

As a "comeover", who lived in this beautiful, windswept place from the age of seven until I left for university, I grew up surrounded by its unique history and customs: watching the TT motorbike races and being mindful to say "Moghrey mie vooinjer veggey" in Manx Gaelic – "Good morning, little people" – as I passed the white Fairy Bridge on the way to Douglas, the capital.

If that all sounds a bit different, well it is. The island (the one in the middle of the Irish Sea, not to be confused with the Isle of Wight, if you please) has its own laws, coins and banknotes with the same value as sterling, and a distinctive red flag bearing the Three Legs of Man emblem. It lets prisoners vote, is home to the Lady Isabella at Laxey, the largest working water wheel in the world, and has just 1.9 per cent unemployment. It is the fifth nation – behind the United States, Russia, China and India – most likely to be the next to put someone on the Moon.

You see, the Isle of Man is not part of the UK or the European Union but is a self-governing British crown dependency that has the Queen – who, confusingly, is the Lord of Mann – as its head of state. It boasts a thriving global financial services industry lured in by favourable taxes. But locals stress any "tax haven" label – with its connotations of banking secrecy and "funny money" – is false.

Party politics has never really taken off there; instead, the vast majority of politicians are independents. Depending on the result on Thursday, the island may edge a step closer to a party system: the Liberal Vannin Party, founded in 2006, wants to usher in party politics and is fielding 10 candidates in this election. The only other political party being represented at the polls is the Manx Labour Party (independent of the UK party), which has one candidate.

Unlike in the UK, where each constituency elects one MP, the 15 constituencies across the Isle of Man, which is 33 miles long and 13 wide, each choose a different number of MHKs. There are one, two and three-seat constituencies. A boundary review commission is looking into this: many of the island's 80,000 residents feel the system is undemocratic. The Chief Minister – the Manx "Prime Minister" – is chosen by MHKs after the election.

Last week, I returned to the "rock" to follow candidates contesting the two-seat constituency of Douglas South on the campaign trail. Standing outside the "wedding cake", the colloquial name for the white building that houses the parliament, Liberal Vannin candidate Kate Beecroft, 58, says it is not right that residents do not know who the Chief Minister might be, and what his or her policies will be, until after the election. The budding MHK, who runs a home care company with her husband, believes party politics will change this, but many residents believe the island is simply too small for a party system.

Among them is the independent sitting Douglas South MHK Bill Malarkey, 60, an electrical engineer by trade. As he knocks on the doors of the local-authority-run pebbledash terraced houses in Anagh Coar, he tells me of the benefits of Manx politics: MHKs are accessible 24/7, with their numbers listed in the phone book. One night, he recalls, he was called out to fix a constituent's leaky sink.

Island voters can be swayed by personalities. The constituency's other sitting MHK, a shopkeeper, David Cretney, 57, of the Manx Labour Party, who I join making house calls on Douglas's Spring Valley estate, round the corner from the island's power station, says party politics would prompt voters to choose candidates on their policies rather than "whether he's a nice person or not".

On the doorsteps, the economy is foremost in voters' minds, as the island tightens its belt. Under an agreement the Isle of Man has with the UK, indirect taxation, such as VAT, collected in both countries is pooled and divided between them according to a formula known as the revenue sharing arrangement. The UK has changed this arrangement, which means that by 2013/14 the island government's revenue will be £175m less than previously estimated. That is equivalent to about a third of its current annual spending on public services.

However, as the retiring Chief Minister, Tony Brown, points out, as we sit in a café under the shadow of the medieval Castle Rushen in his former constituency of Castletown, the island's finances are still rather healthy: it has about £1.2bn in total reserves and no debt. Tynwald is unable to budget for a deficit. Mr Brown claims the government has been "very prudent" over the years, but many of the voters who I meet believe politicians did not control the purse strings tightly enough while the island was enjoying more than two decades of continuous growth.

"When the money was coming in, it was going out too quick," says a retired harbours board worker, Billy Noble, 65, as Mr Cretney and I shelter from the rain and Manx "breeze" in his Spring Valley home.

Back in Castletown, 17-year-old Luca Ciappelli is worried about tuition fees – but for a slightly different reason to his UK peers. The Isle of Man government currently pays Manx pupils' tuition costs but has yet to announce whether it will continue to do so. It is still negotiating with UK universities over next year's fees, which are due to rise to a maximum of £9,000 for English students.

In some ways, not much has changed since I lived on the island. Despite acknowledging it is a safe place to live, Luca and other Castle Rushen High School students list the familiar drawbacks of island life for teenagers: there is nothing to do; it is too expensive to travel off-island; there are not enough good shops. Yet these 16- and 17-year-olds have one thing I never had at their age – a vote.

You see, this island, often dismissed as a quaint oddity, is forever evolving. And I wouldn't bet against it winning that space race.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments