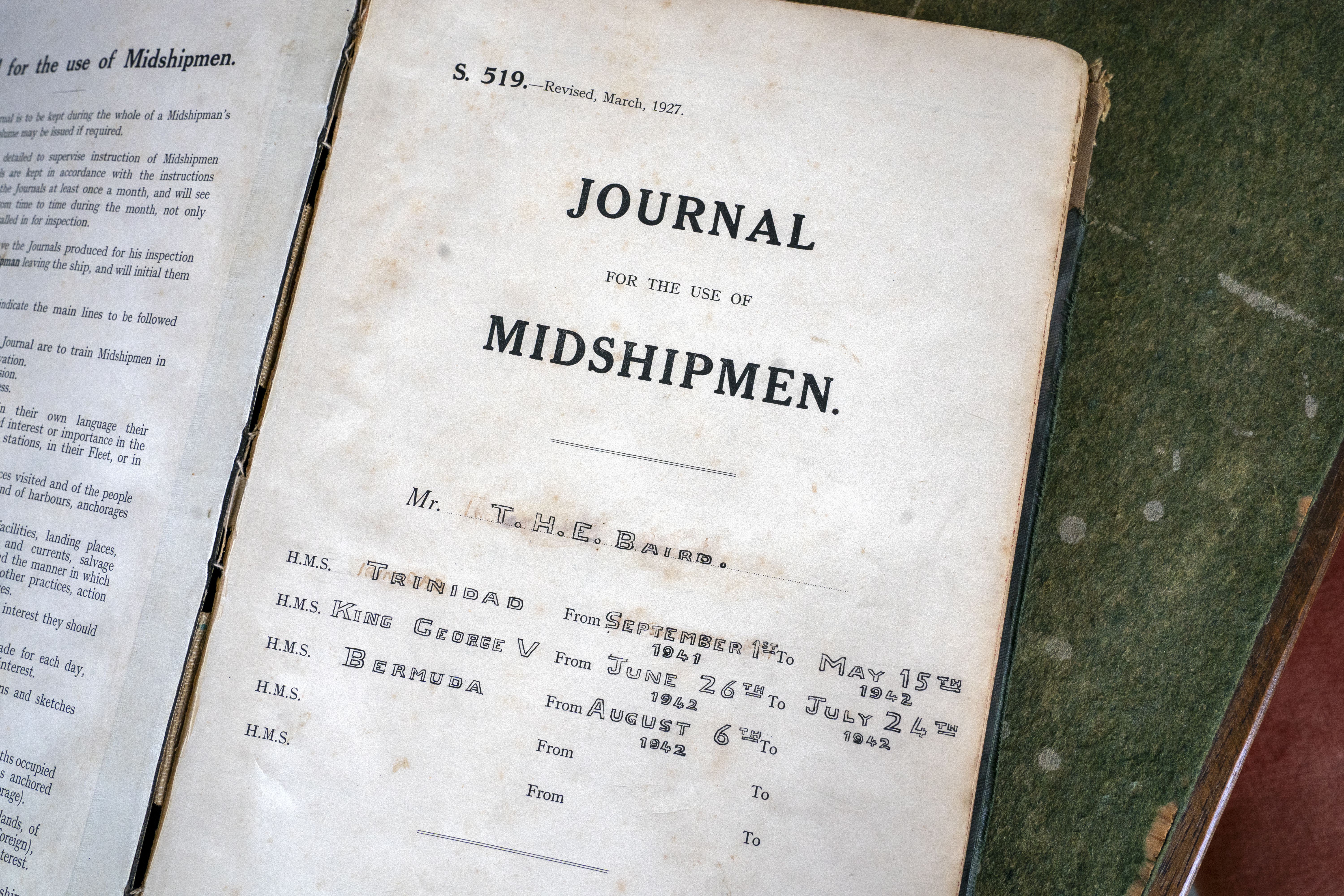

Veteran’s diary written as teenage seaman recalls life in Arctic Convoys

Sir Thomas Baird, 100, said he disliked having to keep the journal and he had hoped it would be lost to the sea when his ship was scuttled.

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The diary of a 17-year-old Navy seaman survived the Second World War – but the 100-year-old veteran who wrote it has told how he hoped it would be lost during Nazi raids on the Arctic Convoys.

Sir Thomas Baird joined the Navy in August 1941 in Plymouth, Devon, and his first impressions are recorded in a journal which midshipmen – the lowest ranks – were obligated to write.

He enrolled in Dartmouth College aged 13 and later became Vice-Admiral Sir Thomas Baird, head of the Royal Navy in Scotland and Northern Ireland, during a 41-year career.

Sir Tom recalled how he hated the diary and hoped it would be lost, but it provides a first-hand account of the war, including a poem describing his desire for “noise and excitement”, bleak boredom, and a Nazi firefight.

An entry from September 1, 1941 described how teenage sailors were “bumped along uneven roads with luggage piled up one end of the lorry” to their digs, and added: “By the end of the evening I knew practically everyone and felt I might have lived among them for years.”

Aged 17, Sir Tom served on HMS Trinidad as part of the Arctic Convoys, which delivered supplies to the Soviet Union in a gesture of support from 1941 after Hitler breached a treaty of non-aggression two years earlier.

The route was treacherous due to its proximity to Nazi-occupied Norway and ice made the ship unstable, but Sir Tom said he was “one of the lucky ones” as around 18 of his friends were killed in 1941, also aged 17.

Nazi warplanes attacked HMS Trinidad near Murmansk, Russia, and she was scuttled by Allied destroyers on May 16, 1942 – which Sir Tom felt was “good news” as it would absolve him from completing the hated journal.

However an eager colleague rescued the diaries from a safe, and Sir Tom was reunited with it the day before he turned 18.

A poem titled HMS Trinidad described his excitement at being “proud to belong of my ship and proud to belong/To a service so great, a tradition so high” as the crew departed from Scapa Flow, Orkney, and its dramatic demise in the Arctic.

It added: “For weeks I was cold, I was bored, I was tired/of those bleak Arctic seas/I was tired of the endless grey day and cold night/I wanted the noise and excitement of a fight/I wanted excitement and danger and thrill/Yet still/We just sailed in those bleak Artic seas.”

It described the firefight: “Planes were roaring!/Guns were flashing!/Men were shouting.

“Until bombs crashed/On to our deck”.

It concluded: “And now the midnight sunshone clear and bright/Beneath a quiet and empty sky/How strange it seemed in that unnatural light/Just to stand and watch her die.”

Around 750 sailors were evacuated, including Sir Tom who was taken to Iceland, and around 50 were killed.

Sir Tom said: “I didn’t like having to keep a journal and have it inspected by an officer. I thought it was good news the ship was going to be sunk, as my journal would be going down with it.

“One of the other midshipmen was going past the gunroom and he collected the journals from the safe – being a well-behaved and responsible person he collected them and gave them to us on board the destroyer. I was made to recommence writing my diary.”

Sir Tom, who has five grandchildren and 10 great-grandchildren, now lives in Symington, South Ayrshire, where his late wife Angela was from.

In 1979 Sir Tom became Flag Officer, Scotland and Northern Ireland – the most senior role – and he retired just before the Falklands War in 1982.