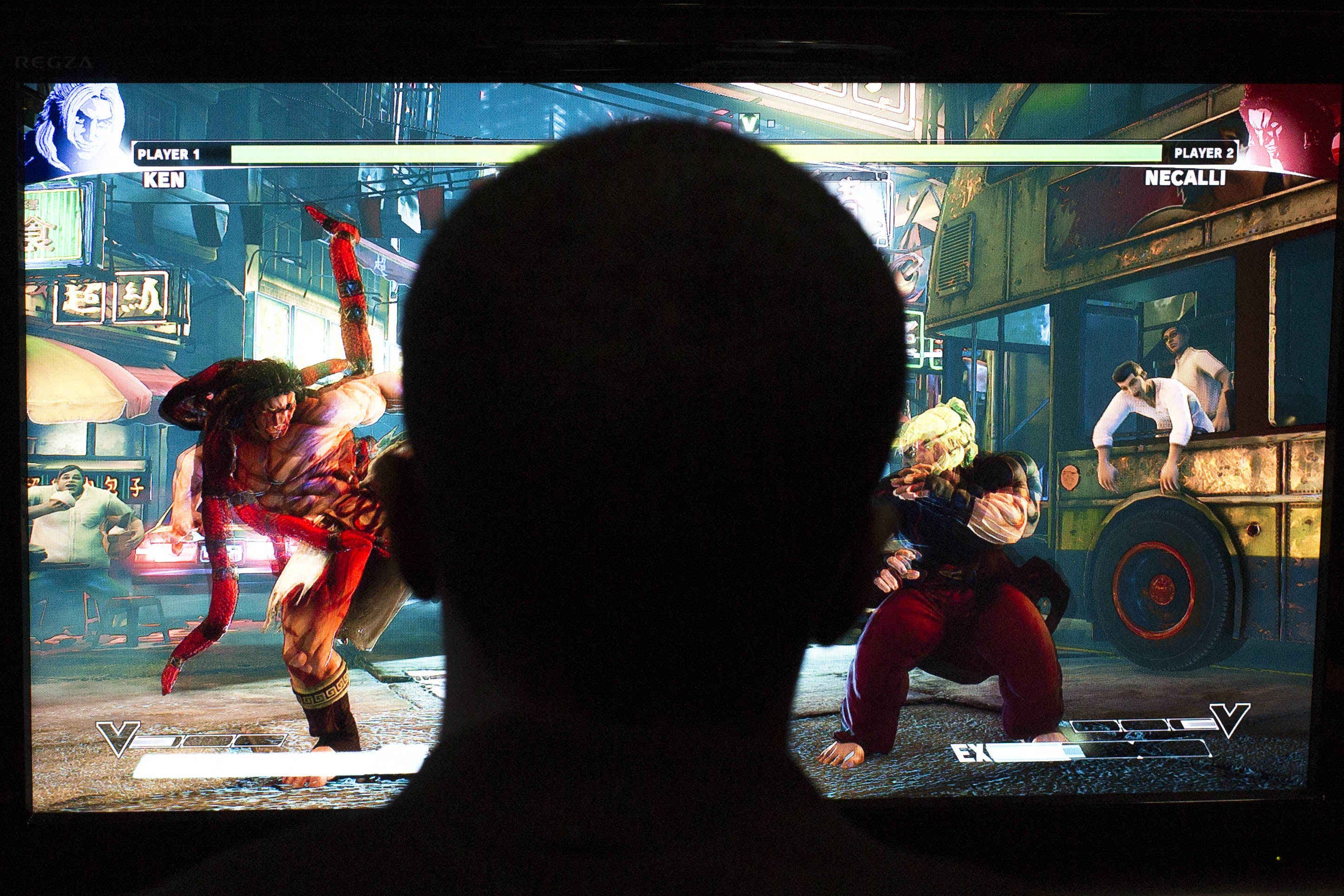

Clinic director ‘was not prepared’ for level of gaming disorders

National Centre for Gaming Disorders has seen many more referrals than expected in first three years.

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The founder of the first NHS clinic created to treat gaming disorders has admitted she “was not prepared” for what she has seen since its opening.

Professor Henrietta Bowden-Jones is the director of the National Centre for Gaming Disorders, an NHS clinic which opened its doors in 2020 expecting to see “no more than 50 patients a year”.

But writing in the Guardian, Professor Bowden-Jones said the clinic has received about 800 referrals in just over three years.

She wrote: “The desperation of the families trying to address the disruption that gaming harms have had on their children is extreme.

“I was not prepared for what we came across, with violence within the home and refusal to go to school being prominent.”

She said most patients are young and male, often 16 or 17, and are likely to have been high achievers before developing a gaming disorder.

“The pattern of harm often starts with a change of circumstance,” she wrote. “It may be a move between schools or a change of home and therefore a geographical distancing from real-life friends.

“It may be a fragmentation of the family or a significant issue with peers, such as bullying, that leads the young person to seek peers online.

“Gradually, the child’s online life becomes a support structure, something to make real life easier to bear.”

The monetisation of gaming via loot box purchases and the advertising of such gambling-like features in games is normalising gambling behaviours in young people

She said arguments at home can spiral into domestic violence and “sometimes people get hurt”.

“I have met parents whose young children ran away from home in the middle of the night to find wifi on the steps of random homes when their own internet connection was switched off by parents,” she said.

While the clinic began to help younger people, she said gamers in their 20s and 30s have referred themselves and the oldest patient is a woman in her 70s.

She said loot boxes, in which gamers spend money to receive extras within the games, were a feature in about a third of referrals.

“The monetisation of gaming via loot box purchases and the advertising of such gambling-like features in games is normalising gambling behaviours in young people,” she told The Guardian.

“We need reassurance that protective regulation of these products will be implemented. We must take online harms seriously.”

The Guardian said the London clinic has treated 855 people since it opened in 2020 with 30 a month since the end of March – more than seven times the anticipated number.