Mistakes will be made when releasing terrorists – watchdog

Independent reviewer of terrorism legislation Jonathan Hall QC said terrorists released for ‘completely correct reasons’ could still reoffend.

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The independent terror watchdog has warned that mistakes will be made around the release of offenders as it emerged the Parole Board is considering letting nearly 100 terrorists out of prison.

There are 92 active and ongoing terror cases, several of which could come before parole judges to be determined next year, depending on how long it takes to gather the evidence needed for hearings.

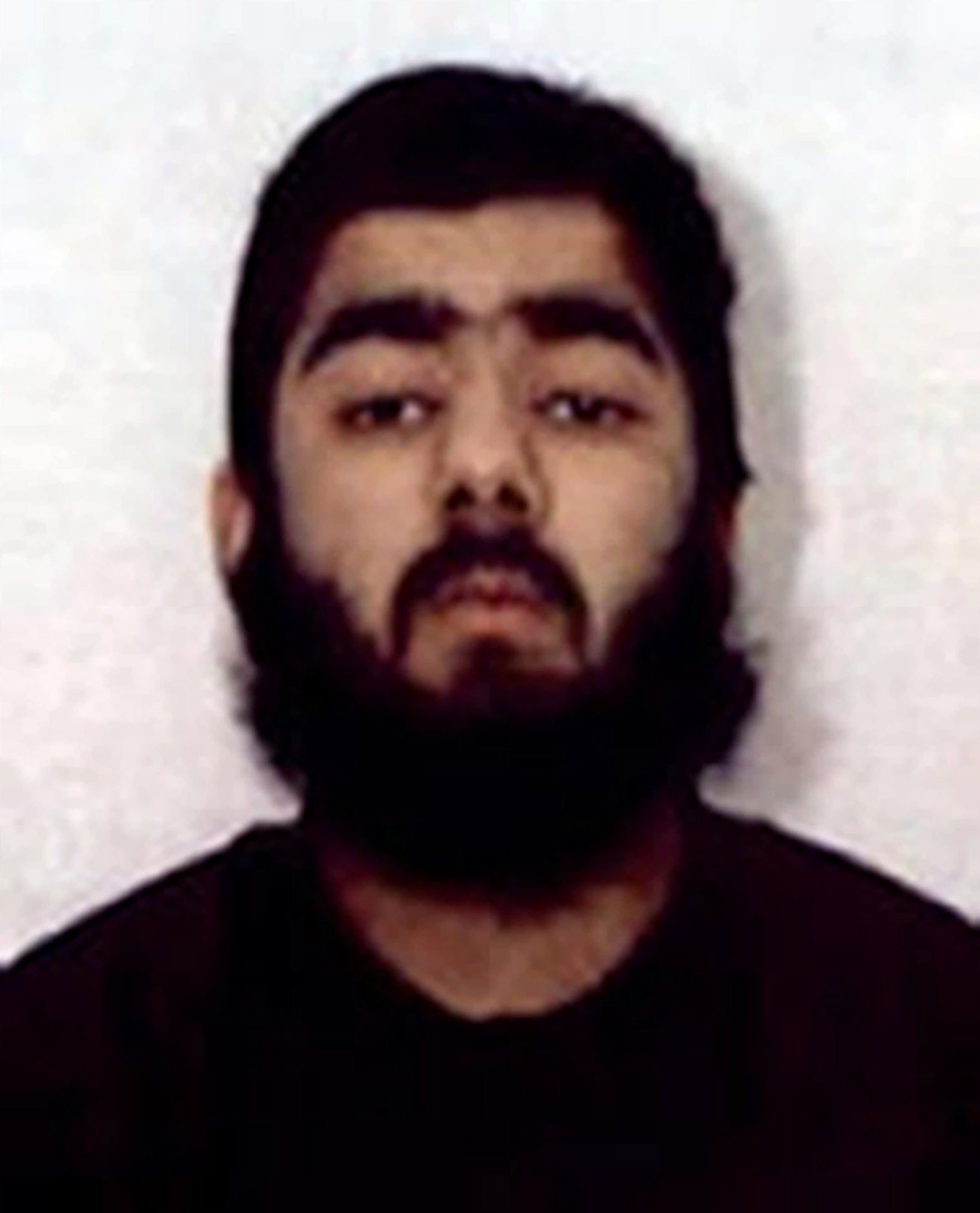

Independent reviewer of terrorism legislation Jonathan Hall QC said some of those freed could go on to reoffend like Usman Khan, who murdered two people in the London Bridge attack in 2019, 11 months after being released from an eight-year sentence for terror offences.

But he added that the Parole Board will be “ultra-cautious” following the Khan case, in which the killer successfully convinced many, including his prison chaplain and his probation officer, that he had reformed.

Mr Hall told Times Radio: “It (mistakes) is going to happen, and sometimes people will be released for completely correct reasons, but something will happen to them once they have been released.

“Usman Khan had been out for a year, but there will be cases of people who are released and maybe five years later they will do something. I think it would be hard to blame the Parole Board for that.

“The Usman Khan case sent shockwaves through the system. It meant that the Parole Board has become very acutely aware of the risk that the wool is being pulled over the eyes of the authorities. They will be ultra-cautious in cases involving serious offenders.”

Emergency laws to block the automatic early release of terrorists were passed in February last year after two attacks in three months were carried out by extremists who had been freed from jail.

Terror offenders must now serve two-thirds of their sentence before being eligible for release – rather than the previous halfway mark – and first need to be reviewed by the Parole Board.

Mr Hall said there is a well-established system for identifying, catching and convicting terrorists, but “what’s really difficult is that stage of letting go”.

He added: “There is real public interest in allowing terrorists to be released and, indeed, to no longer having to manage them once they are no longer dangerous because of the huge financial and opportunity costs if MI5 and if the police have to constantly monitor people – whether by keeping them in prison or by following them around when they have been released – then they lose the opportunity and the bandwidth to detect new and emerging threats.”

Public protection is always our top priority. Any terrorist convicted offender released into the community will be subject to some of the strictest licence conditions available

Some of the cases under review include that of Nazam Hussain, who plotted attacks alongside London Bridge terrorist Khan, and Jack Coulson – who made a pipe bomb in his Nazi memorabilia-filled bedroom and downloaded a terror handbook. Both could have their bids for freedom determined in February.

Terror boss Rangzieb Ahmed – the first person to be convicted in the UK of directing terrorism after heading up a three-man al Qaida cell that was preparing to commit mass murder – is anticipated to have his case ruled upon in March.

In the same month, a decision may be made on whether Jawad Akbar, one of five terrorists who plotted to bomb the Bluewater shopping centre in Kent and the Ministry of Sound nightclub in London in 2004, can be released.

Islamic extremist Abdalraouf Abdallah, who was visited in prison by Manchester Arena suicide bomber Salman Abedi but has denied any involvement in the attack, was recalled to prison for breaching licence conditions earlier this year. He is likely to be reconsidered for release in the first half of 2022, as is Aras Hamid who tried to leave the UK to join fighters with the so-called Islamic State.

Since the introduction of the Terrorist Offenders (Restriction of Early Release) Act 2020, 117 cases have been referred to the Parole Board. So far 11 have been freed and 14 have been refused release.

Terror cases often take longer to consider due to their “complexity” and “go through painstaking and thorough processes” to make sure all necessary evidence is available to panels for hearings, the Parole Board said.

Intelligence from security services forms a “key part” of many terrorist parole reviews and the panels tasked with making the decisions – made up of members including former and serving judges, chief constables, prison governors, prosecutors, psychologists and psychiatrists – require “top-level security clearance” so they can hear sensitive evidence.

Terror cases are a “tiny” proportion of the Board’s caseload – equating to less than 100 of the roughly 16,000 dealt with each year.

But, because of the “critical public protection nature” of the cases, the Board is increasing the number of specialists who can handle them and hopes to have around 70 panel members by early next year.

A Parole Board spokesman said: “Public protection is always our top priority. Any terrorist convicted offender released into the community will be subject to some of the strictest licence conditions available, including restrictions of where they can go, who they can associate with, restrictions on internet use, electronic devices, travel and work.

“They will also be subject to further close monitoring as part of Multi Agency Public Protection Arrangements (Mappa).”