The miners' strike revisited: Digging up the past

After 30 years, and with its cause long lost, the miners' strike should be receding into history. But on returning to the Durham pit village where she grew up, Anne McElvoy finds that the struggle is still a part of everyone's story

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The line Victrix causa deis placuit sed victa Catoni is not one to trip lightly off the tongue. It can be translated as "the winning cause pleased the gods, but the losing cause pleased Cato", and is a quote from Lucan's great civil war epic, Pharsalia, which tells the story of Caesar's rise to the role of absolute leader of the Roman empire – and the battles and betrayals along the way.

Lucan, writing around AD 61, lionised Cato, a historian who had died a century previously, and whose name stood for stoicism, loyalty and stubbornness in his doomed resistance to Caesar and attention to the fate of the conquered. But what Lucan was really pointing out is that it is worth keeping an eye on the lost causes, as well as the successful ones: the vanquished as well as the victors. They tell us about parts of our country and societies which can easily be forgotten. As a reporter on foreign conflicts and domestic upheavals, I have always found Cato a useful ally.

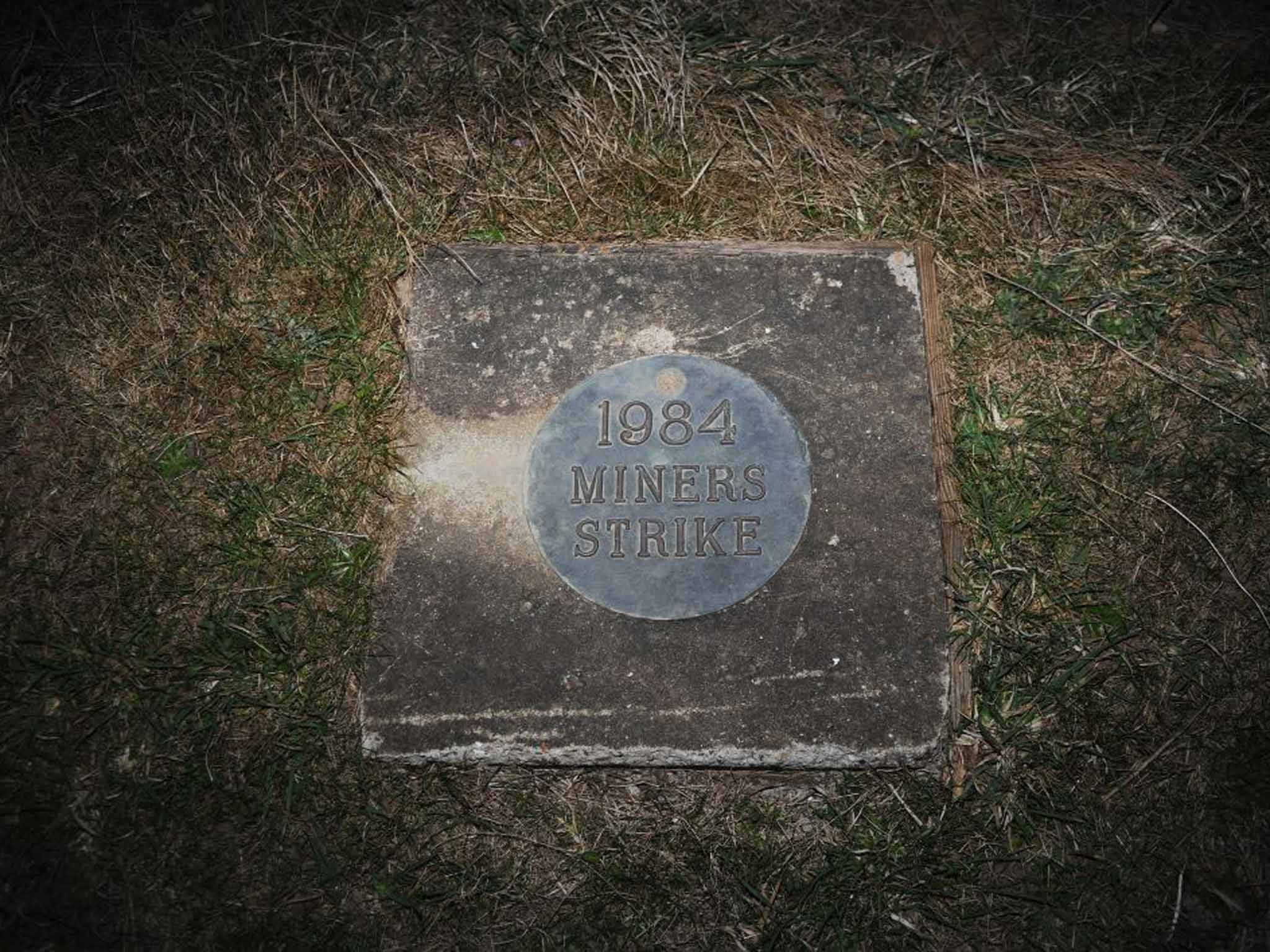

So it is with the miners' strike of 1984-85, one of those acute pinch-points in our recent industrial history, which draws us back to it in this 30th-anniversary year – a period of time which can still feel recent, while being long enough to rank as history.

I say "us" as people do when they really mean "me", because the miners' strike was also a part of my experience of growing up in the former pit village of Dipton, in the north-west of County Durham. My grandfather had been a miner there and, like a lot of pitmen, he never really stopped thinking of himself that way. Well into his eighties, my mother recalled, the words "Vane Tempest" would send him into a rage about the fatality rates and working conditions he had seen as a young man in that colliery. He pronounced the word "capitalist" with the old miners' pronunciation of ca-PIT-a-list. It did not indicate fondness.

But unless you lived in a working pit village, which by the 1980s was becoming rare, the mining traditions had really become vestigial: a grandad's trade, represented by school days out to Beamish and Sid Chaplin's writings. (I can still see the copy of The Thin Seam by my mother's bedside and Chaplin's tough, graceful tributes to the men he had met in the pits who "tend the thin seam of His garment".)

But by the time I was heading off to university in 1984, things had changed abruptly. The miners' strike, which began in March that year, pulled the subject back sharply into the present. It dominated the news bulletins and the talk in the pubs and local shops. It was visual and visceral, with struggles on the picket lines, political leaders betting their fortunes on it, and agit-pop stars asking us which side we were on. Everyone had a view about it (or sometimes more than one at once).

And like the most poignant of political dramas, from ancient Rome to modern politics, it had absolutely implacably opposed figures on either side: two self-made leaders in Margaret Thatcher and Arthur Scargill, bent on one of the mightiest industrial clashes of modern times. Pit closures, which had until then been local troubles, were suddenly in the centre of national life – and the North-east was one of the front lines.

I am not one of those who believes that lost causes are in themselves wonderful things. A lot of them, including this one, were lost for some inescapable reasons: a determined government determined to quash trade union militancy, against a background of a declining industry which even Mrs Thatcher's Labour predecessors had begun to call time on in the 1970s. This was a cause that never looked like a winner. The part of me that looks at the sweep of political change for The Economist would point out that European coal was becoming uneconomical and a nationalised industry was not best-placed to counter that.

Coal was no longer king – and this was a case of what the poet Matthew Arnold in "Dover Beach" called the "melancholy, long withdrawing roar".

But we are not here just to talk about who won and who lost and why, but to find some of the traces now. So with the unsettled feeling of people who are suddenly asked to return to places they have safely locked up in the bank of memory and anecdote, I revisited Easington and Durham this year, 30 years after the strike that marked the final phase of an industry which shaped the region.

The train arrives in Durham on one of those days when those of us in Southern exile marvel at how big and pale the skies can be. Within 10 minutes I am sitting among the wooden panelled rooms of the NUM headquarters, that green-domed, neglected wonder of Edwardian architecture, to meet Alan Cummings, the former NUM lodge secretary in Easington.

The table in front of him looks like a shrine to the strike, with photographs of Easington colliery and scenes from the Easington picketing (Alan is Easington Man "to the bone"). He is also intelligent, stubborn and hard to move on any point. Broadly, he takes the default line of the losing side, namely that the other lot were somehow bound to win. Our Roman friend Cato took a similarly dyspeptic view of Caesar. "Maggie was going to rub our faces in it," he says, a phrase that is going to accompany me round my trip to the old battlefields as I poke into the rights and wrongs of missing ballots and the leadership style of Mr Scargill, which was not exactly a national charm offensive.

Alan, along with a lot of his old NUM comrades, is not on good terms with Arthur – for reasons which quickly become as arcane as only an internal trades union dispute can. I confide that I'm not on the best of terms with the former strike leader either, since he once threw me out of an interview with one of his candidates in the short-lived Socialist Labour Party for asking the wrong questions, and wouldn't allow his female candidate to speak up. "That's Arthur for you," mutters Alan.

Alan says he wasn't for "bloody Marxists saying lunatic, socialist things" either, but a "Progressive Labour". "The strike was right," he repeats. "But we lost 100-nil."

***

If the big picture of a political stand-off is familiar, the granular detail is less so. Why do some people stay on strike to the bitter end and others not? And which symbolic moments sway others? Pits that were "solid", Alan explains, tended to be those centred on a single place. Strikes in the North-east were more easily broken in places that pulled in workers from further afield. If you know the Durham villages, that makes perfect sense. That interweaving of loyalty and of place comes across as strongly as the militancy. I want to know about Paul Wilkinson, the power loader who made history the day he returned to work, and set off the county's worst picket line violence – and signified the beginning of the end for the strike.

For the first six months, the worst of the picket line trouble had been in Yorkshire and Nottinghamshire. That changed on 20 August 1984 when Mr Wilkinson turned up for work at Easington colliery. He was, by all accounts, an immoveable force, who felt that there should have been a ballot, which was relayed as a declaration of a "point of principle". Mr Cummings just remembers Paul "arriving with his dad and saying, 'You and Arthur's army can all fuck off'", which may not be the Gettysburg address, but left no room for doubt about his intentions.

By 24 August, Mr Wilkinson had been smuggled into the pit and entered the record books as he became the sole working miner in County Durham. A tinder box of tensions and resentments duly ignited. Bricks were thrown, cars overturned and police in full riot gear deployed. You can see Easington lightly disguised as Everington in Billy Elliot, just without the fledgling Nureyev to lighten things up. (I am breaking it gently to my Southern friends that not everyone in County Durham is a balletomane.) There was "a fair bit of bother", Mr Cummings adds, which, considering the broken heads, arrests, and a combination of eight police and miners hospitalised after the worst fighting of the strike in the North-east, is masterful understatement.

There are always small ironies in great stand-offs – Paul Wilkinson, the country's most famous strike-breaker at the time, didn't last long in the job after the return. "It was impossible, really," says the former lodge chairman. I note that he sounds more despairing about the black sheep than angry. A long sigh. "Well, he was a bit of a divvy," says Cummings.

Divvy or otherwise, one man's strike break led to a trickle, and then a drift back to work. By the turn of the year, a mixture of financial hardship among the miners and schisms about the strike leadership had left it looking like a lost cause. Soon the rhetoric of victory had been replaced by laments, and fighting funds by solidarity concerts – albeit big enough to fill the Albert Hall a year after the strike. (If you hanker for a time when the Left had the best tunes, this was surely it, from Paul Weller, to Tom Robinson, the Flying Pickets and Billy Bragg.)

These days, Easington is the place you can go to find people celebrating the death of Margaret Thatcher, which is the sort of darkness-versus-light way of telling the story, and fine if you like that sort of thing, which I don't. Not least because it is a London news desk's easiest modus operandi: "Maggie's gone – get someone to call that place in the North-east where they say they'll dance on her grave."

Another problem with this is that it leaves out the many people in the region and beyond who found themselves torn about the strike, aware of the unsparing realities of a declining industry and discomfited by the militant overtones. (By the mid-80s, it was odd by the standards of the democratic world to have a strike leader who railed against fellow miners in Poland's Solidarity movement for being insufficiently communist.)

Yet there was also a deep well of sympathy for the pitmen's plight and a sense of being far from the seat of power, but on the sharp end of its decisions. I knew people who were small-c conservatives in outlook and loathed bolshy Arthur, and yet donated food for the miners and sent money to the strike fund. You could prize law and order, yet worry about the sort of escalation which ends up needing to move police forces around the land and placing them in the impossible position of a "thin blue line" between two fundamentally implacable groups.

There was – and is – a discomfort about the pitilessness of the whole episode. It is one reason why Westminster plays ping-pong even now about who should apologise for what behaviour, which is a sure recipe for ensuring that no one does. We do not lack for images of the strike: it has become a TV documentary and drama staple. At Easington, police videoed protesters, who in turn were videoing them: a kind of Truman Show of broken industrial relations. Without realising it, we had leapt into an era in which the image and the record of an event was to become as significant as what happened. It must have been the most photographed and recorded industrial stand-off in history.

Over at Easington now, I find the ladies who ran the support group and fed the striking miners and their families, all as neat as pins in the local pub. Among them are Heather Wood and her mum Myrtle and friend Faye, now in her fifties but still the "baby" of the miners' wives group because she was the youngest wife at the time.

They are as fierce as any NUM official about the justifications for the strike, but what really binds them is a sense of something endured together and done well. Myrtle's eyes shine as she remembers her role as chief cook to the miners' support group, cooking up lunches – "hundreds of them and not just egg and chips either – my pies were world-famous!"

Heather is the chief talker. "I was always very…" "Articulate," shout back the others, apparently delighted to find Heather lost for a word after four decades. She remembers the gifts and money sent to support the fund. A couple from the South emptied out their attic. A pensioner sent a small weekly postal order. Later, Heather wanted to meet the benefactors. One of her regular donors declined, saying: "I don't want to spoil the illusion."

It's a moot point how much the strike changed the roles of women, but they genuinely feel that they gathered strength from it. "I think we realised that we could just do things: we didn't need anyone's permission," Faye says. "It was a bit of a myth, the whole business about miners' wives being downtrodden. The strike wouldn't have lasted half a year without the women onside."

There is a fair bit of talk about the unfairness of setting up more heritage centres, which makes me fret that my old county will end up as a kind of wall-to-wall Heritage Experience when what it needs are recipes for future prosperity, not just a way of bemoaning what has gone.

Easington today is the sum of its losses, but it is not only that. It has its legacy of high youth unemployment, poor health outcomes and obesity. Like many parts of the North-east, it has youngsters who need better education and preparation for a changed world. This is where I would put my campaigning efforts, on the admittedly unlikely prospect that Easington would elect me. By no means are all former mining communities doomed zones. Some, notably north-west Leicestershire and south Staffordshire, have prospered. We let new generations down if we suggest that history is the same as destiny.

"Oh no," says Alan Cummings (with mock horror at the thought, indeed at most of my thoughts). "You're a mover on-er!" He is not moving on, he assures me. But my small odyssey has reminded me that we don't have to choose. Anniversaries are significant. Memories matter. To walk by the glorious Easington beach, underneath the old railway, and look back on the town, a mixture of the shabby and the proud, is to feel the power of the past. But Easington is not just a museum, nor a collection of miserable anecdotes and bad statistics. I leave Heather sorting out the next steps of her plan to revive the parish church she helped save from closure. She has taken to social media to galvanise support. "One thing about going through the strike is, you know how to organise a meeting," she says. "I'm never off Facebook."

In the next decade, I suspect that the town and the surrounding areas will take on yet another nationally significant role at the centre of arguments about how much of the abundant coal reserves that could not be reached in the deep seam can now be extracted by the hi-tech means of Underground Coal Gasification. The old geology reports of the National Coal Board are being hauled out of storage to explore a potentially valuable energy source, though anyone who lived through the opencast years knows that such enterprises are more disruptive in practice than they sound in theory.

I started out thinking about the strike anniversary as a long goodbye to the Durham coal industry and its legacy. But perhaps the tale of East Durham coal is not so much that "long, withdrawing roar" after all. The place is built on the black stuff. It has its way of being part of the story, because it is part of us.

This article forms the text to Anne McElvoy's speech to the Durham Book Festival, this Saturday, durhambookfestival.com

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments