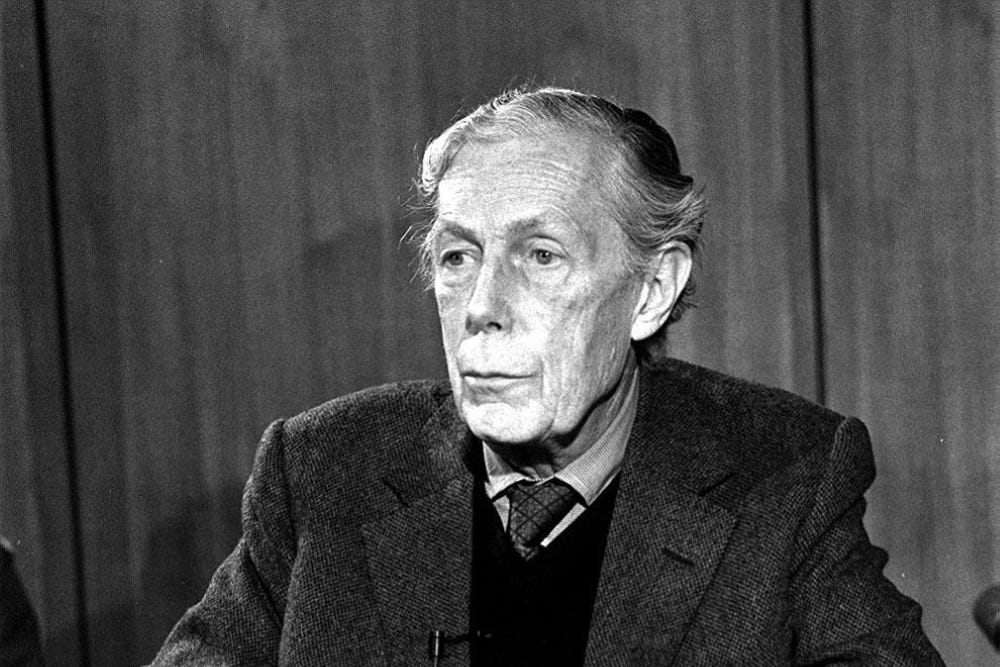

Cambridge spy Blunt feared violence from his KGB controller

Newly-declassified files show notorious double agent refused ‘insane’ order to follow fellow spies Burgess and Maclean to Moscow.

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Notorious double agent Anthony Blunt feared that his KGB handler would turn violent when he refused to join his fellow spies Guy Burgess and Donald Maclean and flee to Russia, according to newly declassified official files.

Amid fears of arrest and that their spy ring was about to be broken up, Blunt’s handler told him to pack his bags and leave the next morning for Paris and from there make his way to Moscow.

However Blunt, a wartime MI5 officer who had become a surveyor of the King’s pictures, regarded the plan as “absolutely insane” and refused to obey.

His vivid account of the frantic days as their group finally unwound is contained in the transcripts of his interviews with MI5 after he finally confessed his treachery in 1963, which have now been released to the National Archives at Kew.

The trio, together with Kim Philby and John Cairncross, had all been recruited by the Russians while or after studying at Cambridge University in the 1930s.

In the years that followed, they were able to work their way into senior positions in British intelligence, the Foreign Office and Whitehall enabling them to pass thousands of secret documents to the Soviets.

However, by the spring of 1951, it was all starting to unravel, as American codebreakers were closing in on Maclean after finally managing to decipher secret messages he had sent while posted in Washington during the Second World War.

Maclean had however by that stage lost contact with his Russia handler after suffering a nervous breakdown as a result of the stress, smashing up the flat of a woman working for the US embassy in Cairo in a drunken rampage.

Philby, who was monitoring events from the US – where he was MI6’s senior liaison officer with the CIA – however hit upon a plan to warn him through Burgess, who was also in the States with the Foreign Office.

Whether by accident or design, Burgess – another notoriously outrageous drunkard – found himself ordered back to London in disgrace after acquiring three speeding tickets in a single day.

When he arrived back in England on the Queen Mary, Blunt was there to meet him at the harbour. As they drove away, he said, Burgess told him: “Look, Donald’s in trouble, and I must contact him at once”.

Burgess’s plan was to wander into Maclean’s office in the Foreign Office and place a note on his desk saying: “Go on talking as if nothing (is) happening but meet me at the Reform Club at 1 o’clock.”

Blunt meanwhile was able to help Burgess re-establish contact with their KGB controller in London, Yuri Modi, codenamed “Peter”.

Before Burgess left the US, Philby had told him the priority was to get Maclean out of the country before he faced the inevitable questioning, which he was in no state to withstand.

However, he was adamant that Burgess – who he had been putting up at his home in Washington – should not go with him, knowing that he would immediately come under suspicion himself due to their close friendship.

Blunt, however, said that he believed Burgess was now desperate to flee as well.

“As you can imagine he was in an appalling state, as were we all. I remember one day his coming to me after a meeting (with Modin) and saying ‘They’ve told me I must go too’,” he said.

“I think he was misrepresenting the truth in the sense that I think … he had persuaded Peter that he would have to go too.”

Blunt said that he believed Burgess’s state of panic had increased after a meeting in the US with Michael Straight, an American who they had recruited to work for the Russians in the 1930s, who had threatened to report him.

“What I’m quite certain of is that Guy realised that – not I think that he was in danger of being arrested – as that, so to speak, his life in England was finished and that the only thing for him was to get out of England altogether,” he said.

“He’d been taking all the wrong kind of drugs together with a lot of drink and so on. He really was in a state of total collapse.”

With just days to go before Maclean was due for questioning, he and Burgess managed to slip out of the country on a cross-Channel cruise ship, which did not require them to show their passports, to France before making their way to Moscow.

Once it became known, the disappearance of the “missing diplomats” caused uproar in the press and a Whitehall search for their accomplices, which saw both Philby and Cairncross forced to resign their posts.

In all the chaos, Modin wanted Blunt to leave too, arranging a rendezvous where he handed a “packet of dollars and pound notes” and instructions to leave for Paris the next morning, from there to make his way to Russia via Helsinki.

Blunt said he regarded the plan as “absolutely insane” and refused to go.

“He (Modin) said ‘Orders are go tomorrow morning but if you don’t go, we meet two months later,'” Blunt recalled.

“I remember being faintly surprised at his not being more violent. I mean, he couldn’t obviously force me to go, but I was rather surprised at his not being more violent.”