Women's suffrage: Rare collection of suffragette posters goes on display to mark centenary of getting the vote

'They were created to be plastered on walls, torn down by weather or political opponents, so it is highly unusual for this material to be safely stored for over a hundred years'

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.A rare collection of suffragette posters have gone on display to mark the 100th anniversary of women winning the right to vote.

The beautifully designed posters - one of the largest surviving collections - were revealed to the public over the weekend at Cambridge University Library.

The selection celebrates the centenary of the Representation of the People Act 1918, which gave the vote to women over the age of 30.

Most of the posters were sent to the library around 1910.

The brown parcel paper in which they arrived was discovered in 2016, revealing the sender to be Dr Marion Phillips, a leading figure of the suffrage movement.

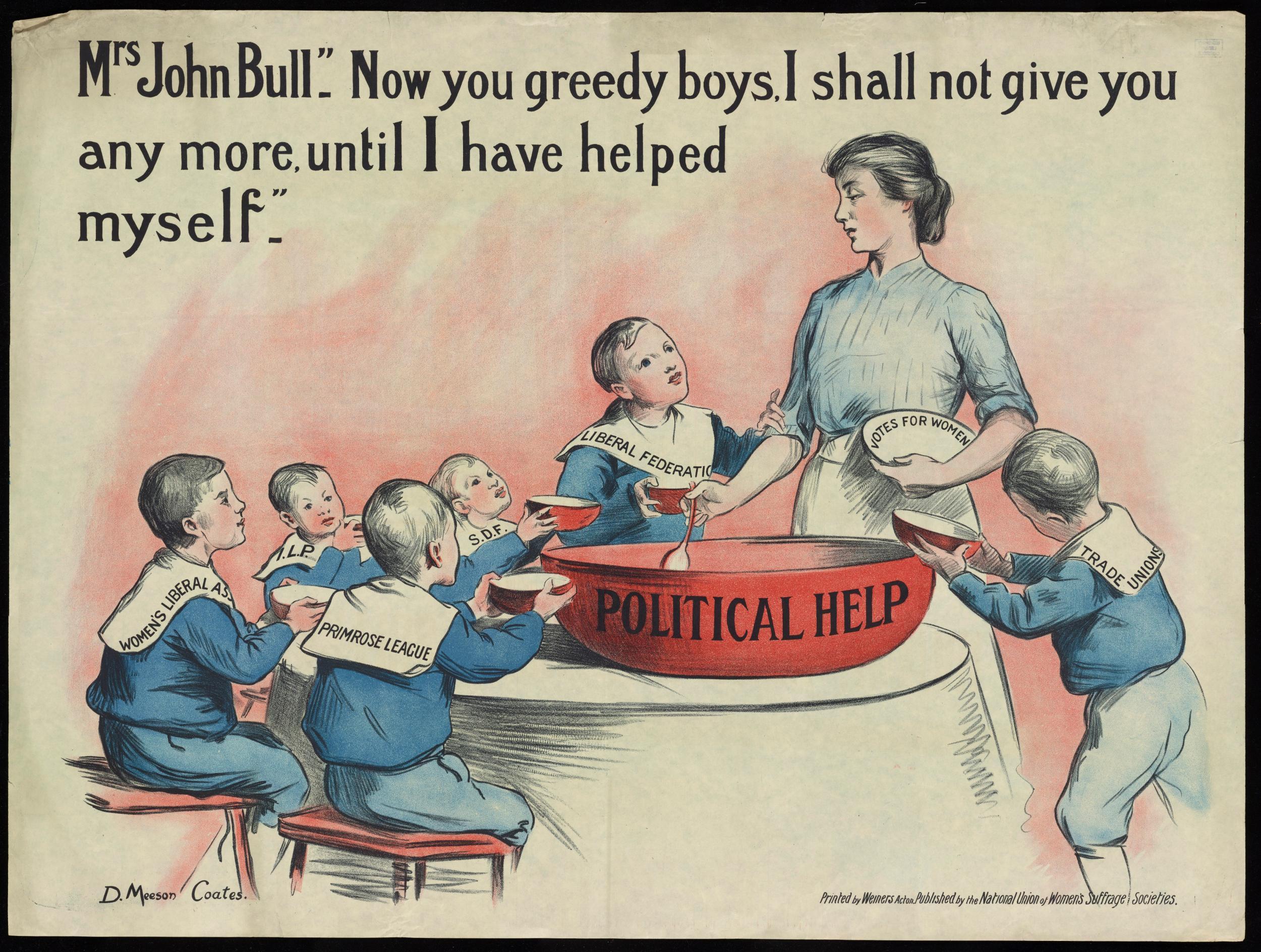

Chris Burgess, exhibitions officer at the library, said: “These posters are fantastic examples of the suffrage publicity machine of the early 20th century. They were created to be plastered on walls, torn down by weather or political opponents, so it is highly unusual for this material to be safely stored for over a hundred years.”

Some posters were for national use, while others were used for local campaigns in Cambridge.

Dr Lucy Delap, a specialist in feminist history at the university's history department, said the first women’s colleges at Cambridge – Girton (1869) and Newnham (1871) – were set up to be a “bedrock” part of the women’s movement.

But the university was far from progressive. A vote in 1897 to grant women full degrees was not only lost, but effigies of women were torched by jeering crowds of male students.

Women were not allowed to become full members of the university until 1948.

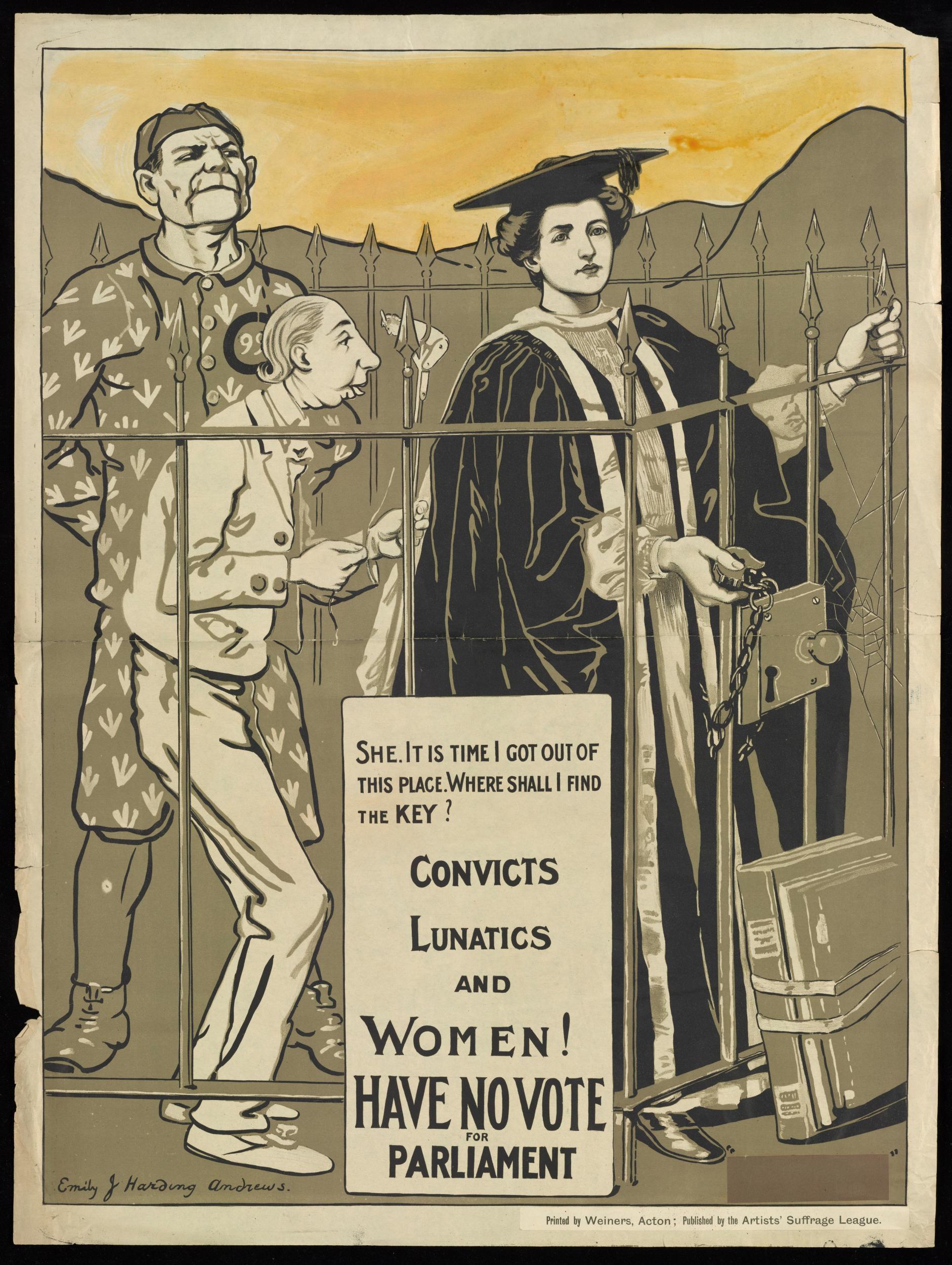

In cities like Cambridge, suffrage campaigns deliberately showed women in academic dress.

One poster depicted a woman in gown and mortarboard caged up with a “convict” and a “lunatic”, reminding academics their educated wives were still lumped in with society’s dregs.

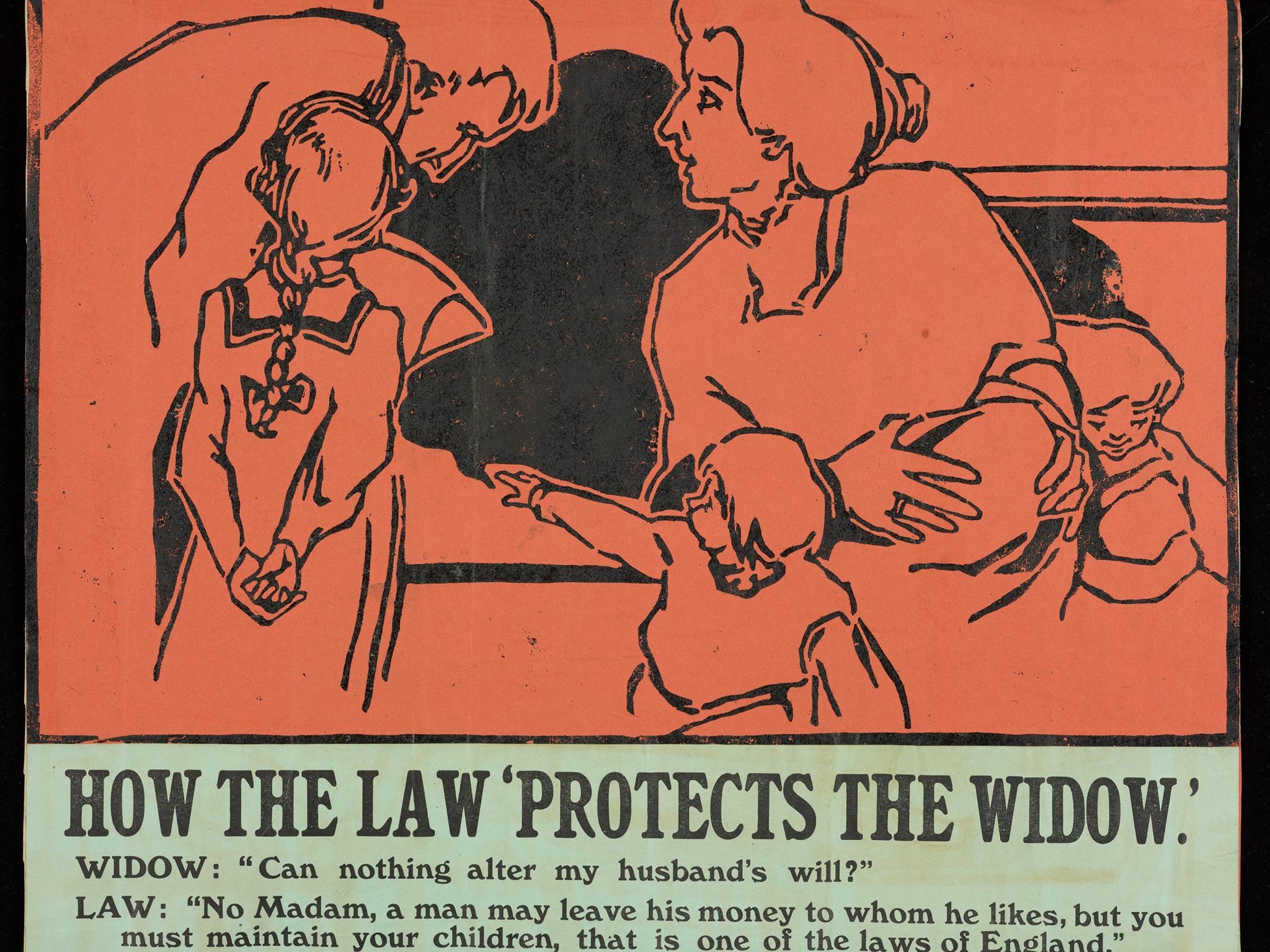

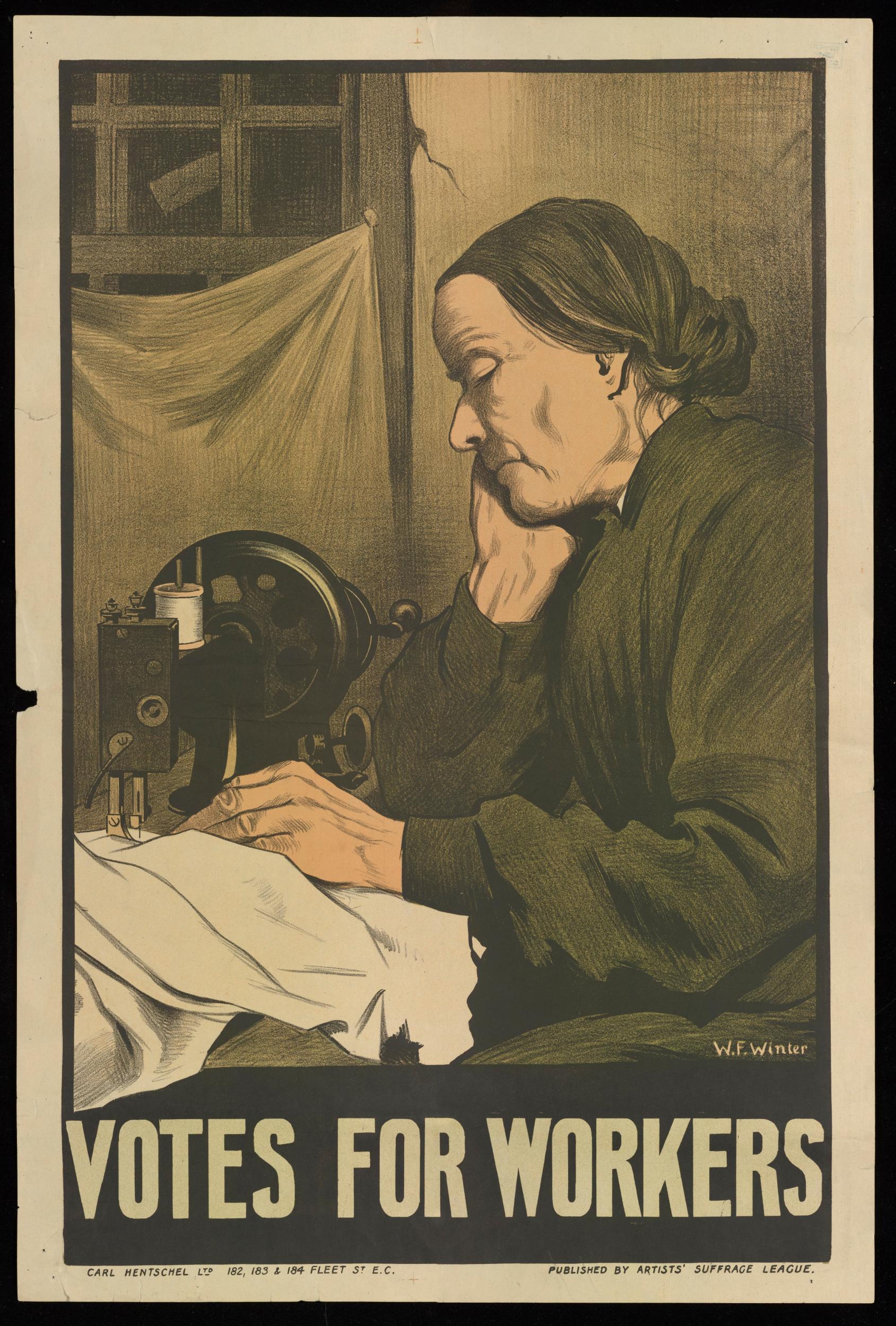

Other posters clearly targeted working-class women in textile factories or making ends meet as seamstresses.

Dr Delap said: “The majority opinion in the UK was against women’s votes. The suffrage movement definitely had to reach out to many women. Campaigning went far beyond the simple equality message to point out how the vote could make a difference in households, at work, on the streets – matters that concern all women.”

As one poster boldly stated: “Our weapon is public opinion,” and to win hearts and minds the movement was at the forefront of innovations in media at the time.

“The movement adopted techniques from the tabloid press – the so-called ‘yellow press’ – using great big headlines, foregrounding visual material, whether photos or cartoons,” said Dr Delap.

She said the suffragists as media-savvy political campaigners.

“If you have the visual juxtaposition of a women in academic dress who’s 5ft tall getting arrested by a burly policeman – that is a picture that’s going to work for the press,” she said.

"They understood that, and were among the first to exploit it to the hilt.”

Some posters explicitly call for "law-abiding" meetings.

Dr Delap said that the movement became divided on tactics, as many felt the continued denial of rights forced more drastic action.

She added: “There were militants who were willing to break the law: smashing windows, destroying golf courses, burning buildings. There were also non-violent actions that broke the law: refusing to fill in census, refusing to pay tax without representation – a range of creative tactics.”

SWNS

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments