Did Churchill really fall for Cara Delevingne’s great aunt in the villa of Edward VII’s former mistress?

The wartime leader who led Britain through its ‘Darkest Hour’ has long been admired as steadfastly faithful to his wife Clemmie. But to the outrage of at least one Churchill historian, a new documentary will claim he made an exception for the ‘ecstatically beautiful’ Lady Doris Castlerosse

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.He was to become the wartime hero who led Britain through its darkest hour, when it stood alone and defiant against Hitler – although he was also, according to one biographer, “probably the least dangerously sexed major politician since Pitt the Younger”.

She, on the other hand, was “the most ecstatically beautiful woman in London”, who maintained “there is no such thing as an impotent man, only an incompetent woman”.

And, it is now claimed, Doris, Lady Castlerosse, proved she was no incompetent by seducing the most seemingly impossible target of them all: Winston Churchill himself.

There had been rumours before, of course.

Now, though, a Channel 4 documentary is to reveal the recorded revelation of one person who might have been expected to know the truth: Jock Colville, Churchill’s private secretary.

In 1985 Colville unburdened himself, on tape, to the archivists at Churchill college, Cambridge, but not before insisting: “This is a somewhat scandalous story and therefore not to be handed out for a great many years.”

“Winston Churchill,” said Colville, who died in 1987, “was not a highly sexed man.

“I don’t think that in his years [of] married life he ever slipped up, except on one occasion, by moonlight in the south of France … He certainly had an affair, a brief affair with … Lady Castlerosse as I think she was called … Doris Castlerosse, yes that’s right.”

If true, this is nothing short of extraordinary. Previous historians have regarded Churchill as having been so devoted to his wife Clemmie (Clementine) that he never strayed from the woman he married in 1908.

This, it is said, was the one husband who could resist the advances of Daisy ‘Wanton’ Fellowes when she offered herself to him lying stark naked on a tiger-skin rug in Paris in 1919.

But Lady Castlerosse, we are now led to believe, was made of even more extraordinary stuff.

“She had only to raise an eyebrow,” declared one admirer.

And what eyebrows they were.

For, as every journalist who reports on Lady Castlerosse must delightedly affirm, she was none other than the great aunt of Cara Delevingne, the supermodel whose own eyebrows have helped make her famous.

Cara’s grandmother Angela – “a noted beauty who evaded a kidnapper in Harrods and declined a part in Gone with the Wind” according to her Telegraph obituary – defied the reservations of her mother to marry Lady Castlerosse’s impecunious brother Edward Dudley Delevingne.

This, it seems, is a story that has pretty much everything.

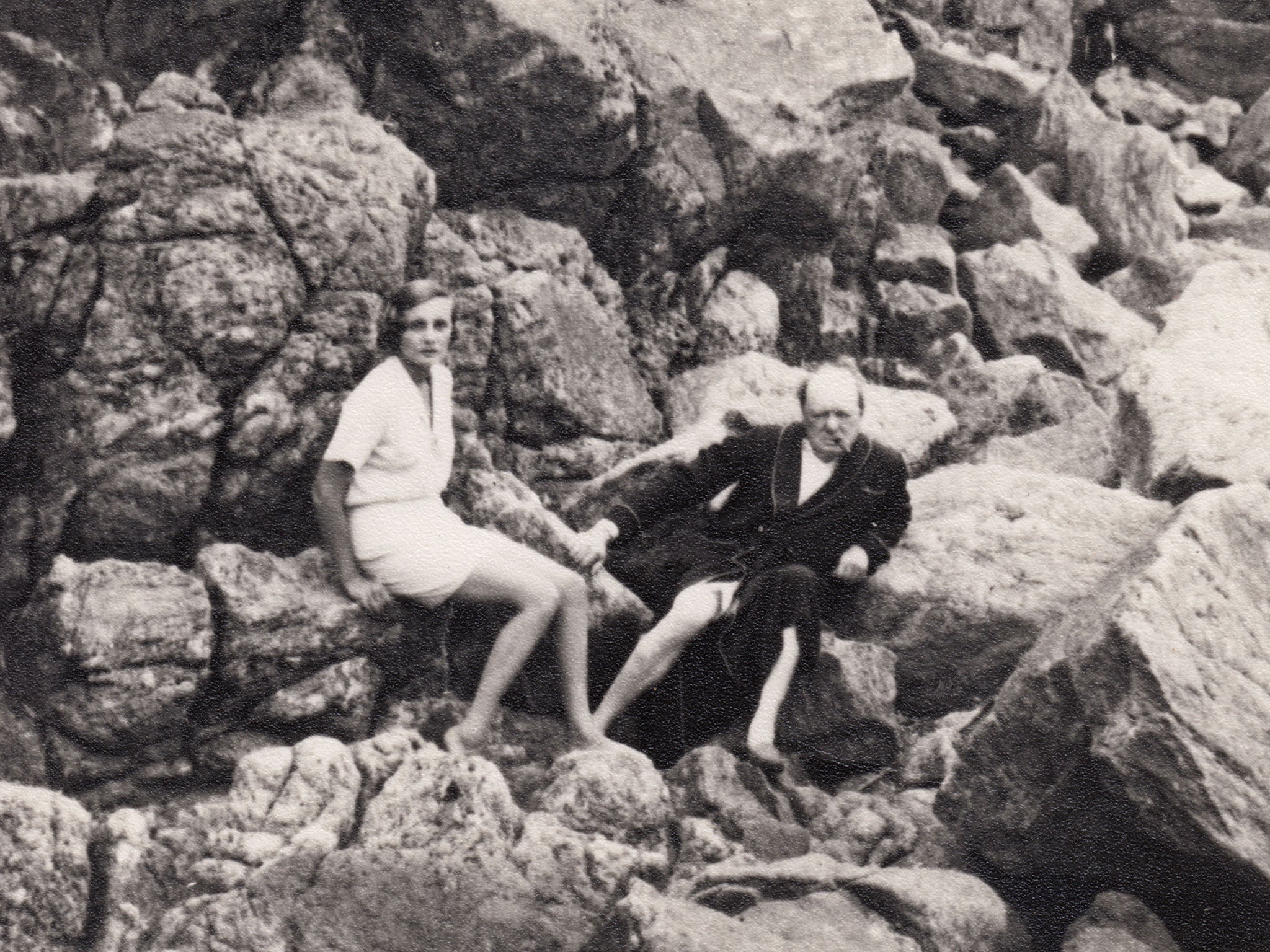

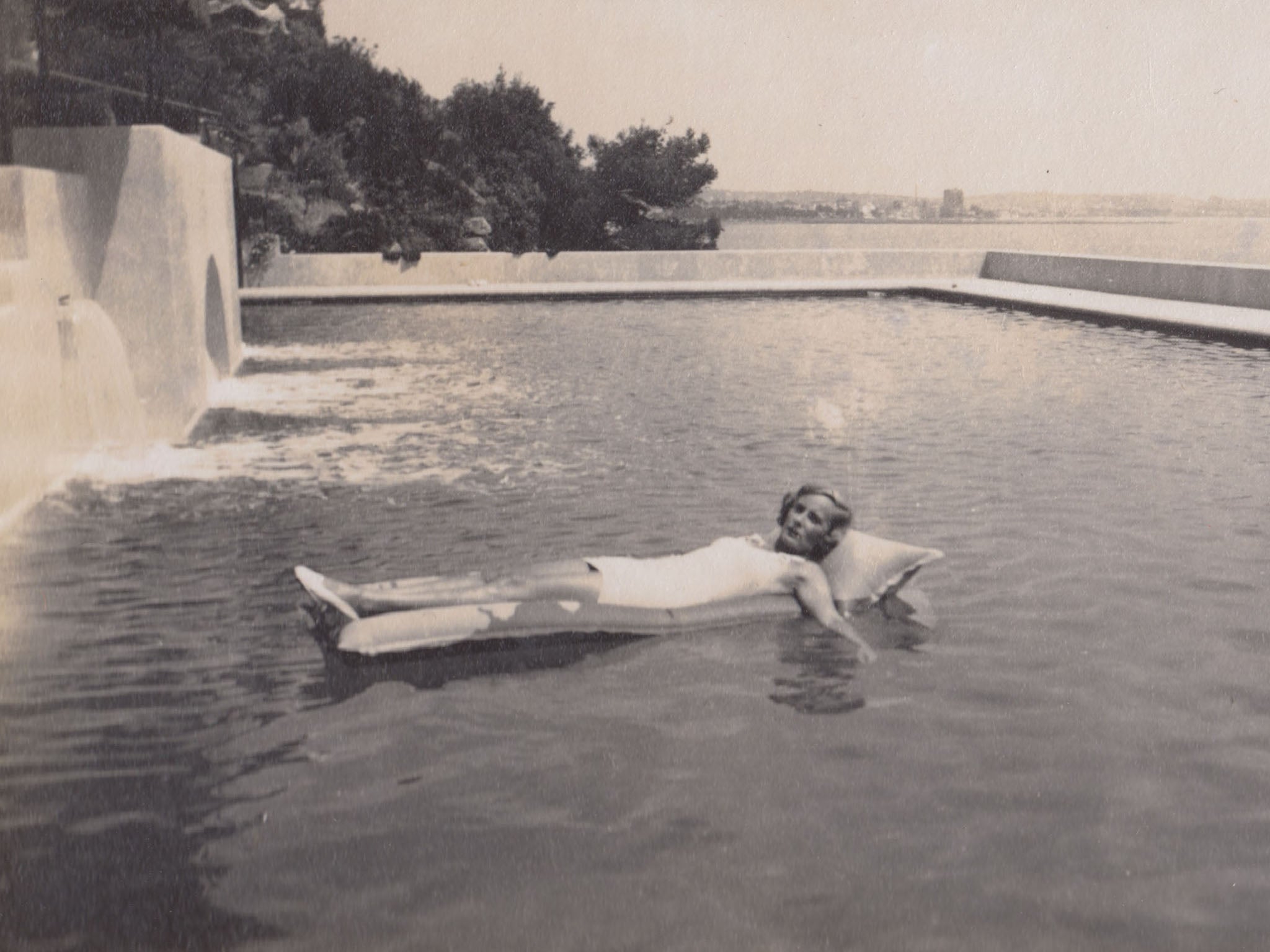

The initial seduction occurred on the French Riviera, at Chateau de l’Horizon, the clifftop villa of Maxine Elliott, herself a possible royal mistress (of King Edward VII), who invited Churchill to be one of the very few heterosexual men staying in what she called her “Adamless Eden”.

It was 1933. Churchill was enduring his “wilderness years”, before wartime duty and glory called.

His wife, who did not care for the louche Riviera set, was not there. Lady Castlerosse was.

He painted her three times, once when she was draped seductively over a chaise longue.

And, according to historians Warren Dockter and Richard Toye whose research underpins the documentary, Churchill did more than take an artist’s interest in her “flower petal complexion and blue eyes with enormously long dark lashes” – (to use the description of another admirer).

Rumour has it he told her: “Doris, you could make a corpse come.” Or “Doris, you could make a saint come,” since rumour rarely bothered to get accurate quotes.

But forget rumour. The academics Dockter, of Aberystwyth University, and Toye, a professor at Exeter, now maintain that there really was an affair and it lasted until 1937, when Doris signalled its end by writing to Churchill: “I hear you are not going to Maxine’s. I’m not dangerous any more.”

The academics are backed by Caroline Delevingne (Doris’s niece, Cara’s aunt), who the documentary makers say has become the first in the family to give a televised interview about the affair.

“My mother [Angela] had many stories to tell about when they stayed in my aunt’s house in Berkeley Square,” Caroline tells the documentary. “When Winston was coming to visit her, the staff were all given the day off.

“Doris confided in my mother about it – they were good friends as well as being sisters-in-law – and so, yes, it was known that they were having an affair.”

And it seems to get better: the apparent confirmation of the affair would suggest that when she seduced the father, Doris had already seduced the son.

It is said that Winston’s boy Randolph had enjoyed Doris’s company in 1932, when he was 21.

That, apparently, was when the maître d’ of the Cavalry Club opened an anteroom to be “confronted by a pair of long, gorgeous legs waving happily in the air”.

So famous were these legs – “the prettiest legs that ever stepped into a punt or danced a foxtrot” – that the maître d’ did not need to see a face to know the identity of their owner.

When “the man between the legs looked up”, the maître d’ saw Randolph Churchill, who was soon shouting at him to: “Get out!”

Who could resist such tales of posh indecency?

The historian Andrew Roberts, biographer of Churchill, admirer of Margaret Thatcher, that’s who.

From his blog on the website of The Spectator comes a great splutter of indignation and, it has to be acknowledged, a pretty compelling case for the defence of Winston.

“This extremely uxorious man with absolutely no track record of infidelity,” declares Roberts, “should not become the latest casualty of the post-Weinstein phenomenon, however much the media loves to drag down our heroes.

“For papers of record to present the story as true, without interviewing any of the plethora of Churchill historians, or members of the Churchill family, before they trash the reputation of the Greatest Englishman, is a disgrace.”

It was not immediately clear whether Roberts, author of Hitler and Churchill, Eminent Churchillians and the soon-to-be published Churchill: Walking with Destiny, was aware of the involvement in the documentary of Dr Dockter and Professor Toye, both of whom have written books on Winston Churchill.

But it was pretty clear he didn’t like the documentary.

Roberts said Jock Colville’s taped allegation of Churchill’s affair had not escaped the attention of previous historians.

“Having been researching a biography of Churchill for the past four years … I listened to it [the tape] many months ago, as has Allen Packwood, the director of the Churchill Archives. And Colville actually said the words to another historian, Dr Correlli Barnett, back in 1985.

“When I heard the tape, I decided to investigate the allegation closely – and found that the facts, and other correspondence in the Archive, simply do not support it.”

For one thing, says Roberts: “The alleged affair took place in 1933-37, but Colville did not become Churchill’s private secretary until May 1940, so this is at best second-hand information, and Colville does not say that Churchill ever spoke to him about it.

“He was also speaking half a century afterwards, an absurdly long period of time for historians to take oral evidence seriously.”

Churchill painting Lady Castlerosse thrice meant nothing. He painted Clemmie three times, says Roberts.

“He also painted Sir Walter Sickert’s wife Therese, Arthur Balfour’s niece Blanche Dugdale, Sir John Lavery’s wife Hazel, his own sister-in-law Lady Gwendoline Churchill, his secretary Cecily Gemmell, his wife’s cousin Marryot White, and Lady Kitty Somerset. There is no suggestion he was sleeping with any of them.”

Nor is the historian swayed by the testimony of Cara’s aunt: “The fact that the Delevingne family, including the supermodel Cara and others who were also not alive at the time, claim that an affair took place is equally flimsy evidence. Plenty of people like to claim notorious links with the famous, as Cara herself must have discovered by now.

“Similarly, the sly insinuation that servants were given the evening off so that Churchill could have sex with Lady Castlerosse can be easily explained by the fact that they wanted privacy to talk and gossip. Servants were known to sell overheard information to newspapers.

“Even palace servants were not allowed into the weekly lunches that Churchill had with the king during the war.”

At least Roberts confirms the affair with Randolph.

But he does cite, in evidence for Winston, something that might be a little hurtful to the memory of Doris.

“We know from the memoirs of people who stayed at the Chateau de l’Horizon,” says Roberts, “that Churchill believed Lady Castlerosse to be extraordinarily dim; she did not know that the League of Nations was stationed in Geneva, for example.

“Would Churchill have really put up with such an ignorant mistress for the four years alleged by this programme?”

Well, the documentary makers might wish to counter, Lady Castlerosse’s life story would suggest she was hardly dull.

She was born a humble haberdasher’s daughter in south London in 1900.

Doris followed her dad into the clothes trade by selling secondhand evening dresses to actresses and chorus girls, which gave her an entrée into the demi-monde of nightclubs and rich, louche men.

It wasn’t her dressmaking skills that made her fortune.

She mastered a sexual technique so powerful that, as one of her lovers put it: “If you come across one of those, you sign away your kingdom.”

To assist with this process, Doris is said to have simplified her surname from Delevingne to “Delavigne”, because it was easier for rich men to spell on a cheque.

Getting a real kingdom, however, allegedly eluded her because when she went for Edward VIII, she found Wallis Simpson already barring the way.

And according to Doris’s biographer, Lyndsy Spence, author of The Mistress of Mayfair, when Edward’s brother Prince George attended one of Doris’s parties he got a telling off from his father King George V.

But Doris did get a Viscount, Valentine Browne, Viscount Castlerosse. They married in 1928. He was smitten, she probably wasn’t.

The balding viscount was apparently so fat he couldn’t bend down to tie his shoelaces. And he didn’t have any money to go with his title.

When Viscount Castlerosse’s mother, Lady Kenmare, found out about the secret Hammersmith register office wedding, she disowned her son and refused to meet his bride.

Which meant Doris had to continue winning the affections of other wealthy men, to the fury of her husband.

The Castlerosses eventually opted for taking separate suites at Claridge’s, conducting their epic rows in the hotel’s corridors.

They divorced in 1938, meaning the affair with Churchill (senior) – if it happened – was conducted while Lady Castlerosse was, at least technically, married.

By then Doris had acquired tastes way beyond her beginnings, which had also included a stint as an 18-year-old pantry maid.

She could send a chauffeur on a 400-mile round trip from L’Horizon to retrieve a swimsuit left behind in London – (because, after all, it showed off those famous legs to such great advantage).

She would buy 200 pairs of couture shoes at a time, especially after she moved – with Margot Hoffman, her wealthy American lesbian lover – to the Palazzo Venier dei Leoni beside Venice’s Grand Canal.

According to Judith Mackrell, author of The Unfinished Palazzo, during her first Venice season the parties at the Palazzo Venier dei Leoni were graced by the presences of the likes of the American actor Douglas Fairbanks and a youthful Prince Philip of Greece. (No one is suggesting Doris and Prince Philip ever enjoyed Churchillian relations).

But then came the war, which made Churchill a hero and Doris’s new home of Italy enemy territory.

She fled with Margot Hoffman to New York.

Margot, though, tired of her and her behaviour.

Alone, far from home, and with her looks now fading, Doris was reduced to pawning her diamonds.

According to the Channel 4 documentary, when Churchill went to America to see President Franklin Roosevelt in the summer of 1942, the two “former lovers” dined together in Washington.

But, Toye and Dockter claim, Churchill came to worry about THAT portrait – the one of the younger Doris reclining on the chaise longue – possibly falling into the wrong hands, leaving him vulnerable to blackmail or the subject of a damaging newspaper story.

It is believed that in September 1942, one of Roosevelt’s advisers, Harry Hopkins, arranged for Doris to return home on a ship to England.

Viscount Castlerosse was waiting for her in London. According to Lyndsy Spence he had written to Doris offering to remarry her.

When she stepped off the train, in the dark of the wartime blackout, all was tender reconciliation between them. But, says Spence, when the viscount saw the older, faded Doris by the light of a Dorchester hotel room he was so shocked by her haggard appearance that he scurried back to Enid, Viscountess Furness, “an Australian wine heiress and serial widow”.

Running out of options, Doris sent a telegram to the New York pawnbroker, telling him to sell her diamonds. Little did she know that selling diamonds during wartime was illegal and her telegrams were being intercepted by Scotland Yard.

Doris was visited by detectives, and left fearing a jail sentence.

And now, in the eyes of the high society that had once embraced her as the most ecstatically beautiful woman in London, Doris had resumed her natural status as a “common little demi-mondaine” – as one of them called her.

She was even lower than that to some of them.

By heading for America Doris had, in their eyes, deserted England in time of war – during its “Darkest Hour”, to borrow the title of the latest film to celebrate her old L’Horizon companion Churchill.

In her book The Riviera Set, the author Mary Lovell recounted how, in the corridor of the Dorchester, Doris happened upon an earl with whom she had once had “a dalliance”.

“He cut her dead but muttered aloud as they passed that she was a traitorous b***h.”

And then, one morning soon afterwards, staff at the Dorchester unlocked Doris’s door with a master key and found her in bed, unconscious, an empty pill bottle at her side. The fatal overdose left her dead at the age of 42.

Churchill’s painting of her in her chaise longue glory, the documentary makers suggest, was discreetly retrieved by Churchill’s friend Lord Beaverbrook after a visit to Doris’s brother Dudley Delevingne, grandfather of the modern beauty Cara.

And so the mystery of what happened between Churchill and Lady Castlerosse remains unresolved.

But having heard of her life and her cruel end who, beside perhaps a Churchill relative and a historian or two, could begrudge this remarkable woman her moment of posthumous fame?

Perhaps the story of the lady and the leader is much like Doris in her prime: irresistible, but of questionable virtue.

Churchill’s Secret Affair is on Channel 4 at 8pm on Sunday 4 March

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments