British institutions 'prioritise reputation of political leaders over children', warns child sex abuse inquiry

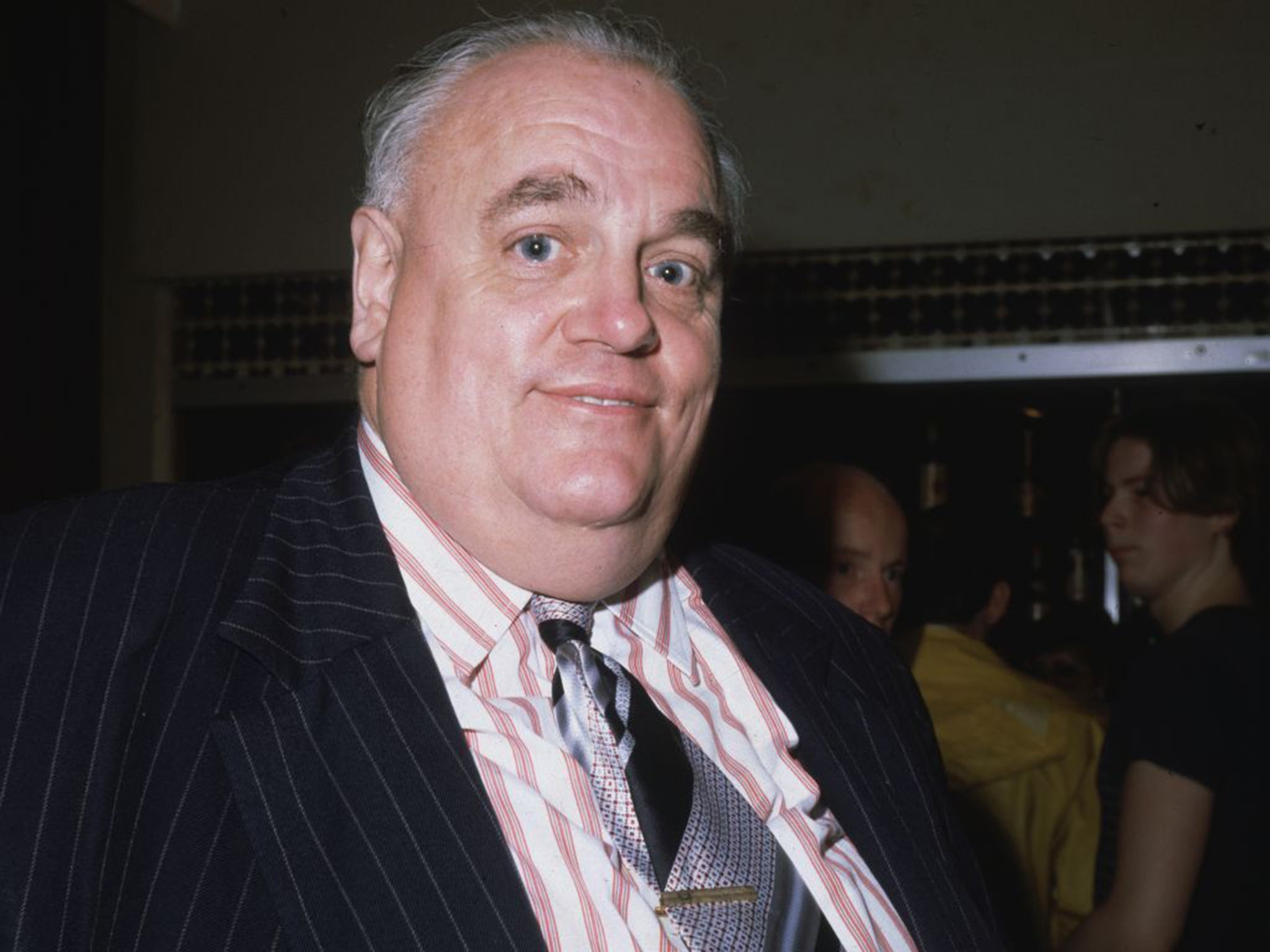

Liberal politician Cyril Smith is among the high-profile figures considered by the inquiry

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.British institutions are prioritising the reputation of political leaders and their staff over the sexual abuse of children, an inquiry has found.

The Independent Inquiry into Child Sexual Abuse (IICSA), which was started in 2014 in the wake of the Jimmy Savile scandal, has heard evidence of horrific crimes linked to children’s homes, schools, the Catholic and Anglican churches and government migration programmes.

“The inquiry considers that all too often institutions are prioritising the reputation of political leaders or the reputation of their staff, or avoiding legal liability, claims or insurance implications, over the welfare of children and tackling child sexual abuse,” an interim report concluded.

“Government must demonstrate the priority and importance of tackling child sexual abuse through its actions.”

One survivor described being abused by an unnamed “pillar of the local establishment”, who had powerful friends and considerable influence.

“It was an open secret that he molested the boys in his charge,” he added. “All child molesters are lowlifes. But some are lowlifes in high places.”

Cyril Smith, the late Liberal politician who was knighted by Margaret Thatcher's government even after police pushed for him to be prosecuted over the sexual abuse for young boys, is the most high-profile figure considered by the wide-ranging investigation so far.

It will go on to examine allegations of child sexual abuse by “people of public prominence” in Westminster and potential cover-ups, grooming gangs in Telford, Rotherham and other areas, youth detention centres, the church, Nottingham councils and other authorities.

The inquiry warned that for decades responsibility for child sex abuse has been deflected away from perpetrators and institutions, who have failed to accept the crimes ever took place or denied the harm caused.

More than 1,000 people have taken part in the inquiry’s Truth Project so far and there have been five public hearings, seven seminars and several published reports.

“Society is still reluctant to discuss child sexual abuse openly and frankly ‒ this must change to better protect children,” the report concluded.

“Children are still accused of ‘child prostitution’, ‘risky behaviour’ and ‘promiscuity’ and, as a result, continue to feel blamed or responsible for the sexual abuse they have suffered rather than being the victims of serious criminal acts.”

A third of survivors giving evidence to the inquiry’s Truth Project reported depression and a lack of trust in authority, while 28 per cent had considered suicide. One fifth had tried to kill themselves and another 22 per cent had self-harmed.

Panic attacks, low self-confidence, obsessions, eating disorders, and alcohol and drug use were also reported by people who gave distressing accounts of the impact of flashbacks and trauma throughout their adult lives.

“I could be in a party and having the best time of my life, but I could smell something or somebody could say something or somebody could touch me and I’m right back to the abuse,” said one survivor. “Until the day I die that’s never going to change.”

Around 53 per cent of victims participating in the inquiry are female and 46 per cent male, aged 21 to 95.

The overwhelming majority – 94 per cent – were sexually abused by men. For six out of 10 the ordeal started when they were aged four to 11.

Around a quarter were abused by teaching or educational staff and 12 per cent were abused by other professionals such as medical practitioners, social workers or police.

One in 10 female victims became pregnant and some children contracted sexually transmitted diseases from attackers.

The inquiry also heard that abuse is increasingly taking place online, with police seeing an 700 per cent increase in referrals since 2012/13 and perpetrators going to ever greater lengths to hide their activity.

IICSA’s research found that more than two thirds of British adults did not feel comfortable discussing child sexual abuse and called for an urgent change of attitude to better protect the vulnerable as one of 18 recommendations.

It also called on a new law to ensure victims of child sexual abuse are given the same protections in civil courts as vulnerable witnesses in criminal courts, amid reports of aggressive cross-examination by barristers and even the perpetrators themselves.

The inquiry repeated long-running calls by campaigners for the Criminal Injuries Compensation Authority (CICA) to stop denying claims for victims committed crimes as a result of their abuse and allow applications from people rebuffed because of the archaic “same roof” rule.

Officials said all police officers wishing to progress to senior rank must be accredited in preventing and responding to child sexual abuse and the departments for education and health should increase checks on care workers and chaperones.

Professor Alexis Jay, chair of the inquiry, said: “We have much work still to do and evidence to hear – we will hold a further eight public hearings in the next 12 months alone, but we are making good progress.

“I believe we are on target to do make substantial progress by 2020 and to make recommendations which should help to ensure that children are better protected from sexual abuse in the future.”

Theresa May established the inquiry, which is expected to cost up to £100m as home secretary in 2014, to examine how UK institutions handled their duty to protect children from sexual abuse following the Savile scandal.

But it quickly became the subject of controversy following the resignation of its first two intended chairs – Baroness Butler-Sloss and Fiona Woolf – within just four months.

Amid objections to the probe’s formation and scope, it was reconstituted in February 2015 as a statutory inquiry and given increased powers to compel sworn testimony and to examine classified information.

Dame Lowell Goddard, a New Zealand high court judge, was the third chair appointed but she too stepped down over the magnitude of the investigation and its “legacy of failure” in August 2016 and was succeeded by Professor Jay.

Controversy has continued, with the Survivors of Organised and Institutional Abuse formally withdrawing in June, calling IICSA “not fit for purpose” and accusing it of marginalising victims.

Presenting the report to the Houses of Parliament, Amber Rudd said the government would give its findings “careful and proper consideration”.

The home secretary added: “I would like to thank Professor Jay and the Panel for their continued work to uncover the truth, expose what went wrong in the past and to learn the lessons for the future.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments