Toynbee Hall inspired Beveridge and introduced Lenin to muffins – but it is not a place of the past

As the hall reopens after a £17m upgrade, Adam Lusher finds the east London building’s history, rooted in the poverty of the Victorian era, is repeating itself

It stands where gastropubs now jostle beside the old East End of Petticoat Lane market, where streets are overshadowed by the gleaming towers of the modern City of London. Amid such bustle, it is easy to overlook the lower rise, altogether more modest Toynbee Hall, and still easier to miss its significance. Yet this is the place that provided formative experiences for two key architects of the welfare state, William Beveridge and Clement Attlee.

This is the place that can claim a pivotal role in the creation of social justice initiatives such as the Child Poverty Action Group. It is where the Poor Man’s Lawyer scheme started in 1898, and where free legal advice is still offered today – along with debt counselling, investigation of social problems and many other community services.

More than a century after Toynbee Hall opened in 1884, it remains a place of pilgrimage for researchers and innovators the world over, seeking out the institution where so much began, and where so much is still being done. And now, after a £17m restoration and redevelopment, chief executive Jim Minton is determined the reopening of the Grade II listed building should be marked by an exhibition showcasing Toynbee Hall’s history as a “powerhouse for social change” and suggesting what it could do in the future.

“So much did happen here and so much has been inspired by here,” he says. “This is a great moment to open the place back up again, to show the community what they have achieved and to say, ‘Let’s achieve even more in the future’. Because the problems have not gone away”

There is, of course, a certain irony in that last point.

Toynbee Hall was created to help lift the East End out of poverty but continues to confront the same issues of low incomes, high debt and poor housing that affected the area in 1884 – with contemporary twists.

Since the Brexit vote, says Minton, “our free legal advice service has started dealing with questions from people from other parts of Europe who have heard something, or been told something by their employer.”

While in the 1880s the head of Toynbee Hall described casual labour – the system that saw men massing outside dockyard gates hoping to be picked for a day’s work – as “the hardest problem of east London”, there seems something of a modern echo when Minton notes: “Over the past 10 years, we have seen a significant change towards in-work poverty, among people in insecure employment, or on zero-hours contracts.”

And yet, when Toynbee Hall opened in the 1880s, it did so during a decade that was supposed to herald a new and better beginning. “It was the end of an epoch,” recalled Winston Churchill. “The great victories had been won. Slaves were free. Conscience was free. Trade was free. But hunger and squalor were also free; and the people demanded something more than liberty.”

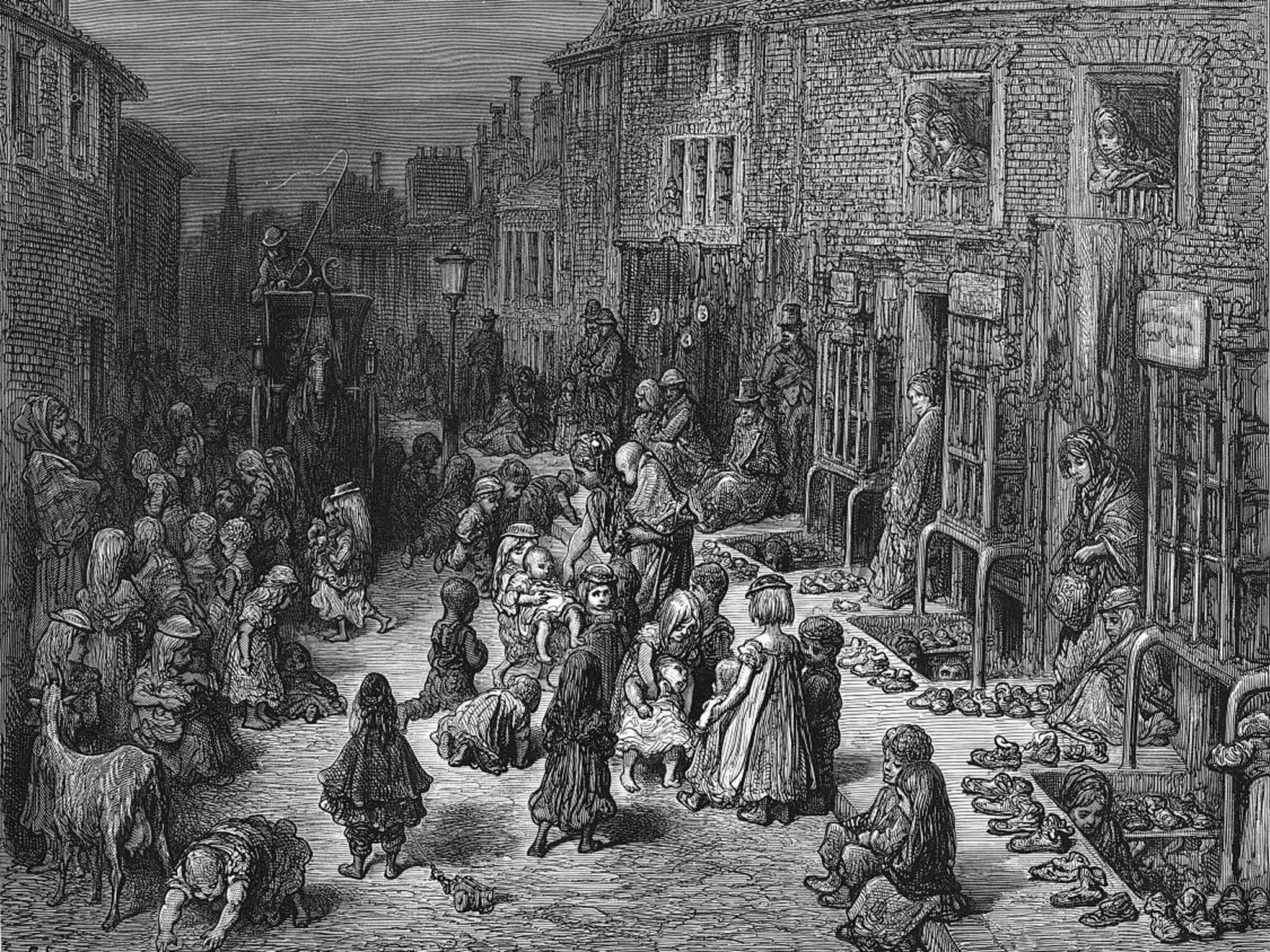

In 1883, Reverend Andrew Mearns would shock middle-class Victorians with The Bitter Cry of Outcast London, his pamphlet exposing the horrors within the “rotting and reeking tenement houses” of London’s “great dark region of poverty, misery and immorality”.

In 1888, Jack the Ripper would add fresh horror with his Whitechapel murders, virtually on Toynbee Hall’s doorstep. And in the parish of St Jude’s – occupied despite the bishop’s warning that it was “perhaps the worst district in London” – Reverend Samuel Barnett and his wife Henrietta were well-placed to separate grim reality from lurid sensationalism.

The reality was plenty bad enough. It featured whole families living in a single room, whole neighbourhoods sharing a single lavatory, with sewers running down the middle of streets. And yet the casual labourer was often paying more in rent per cubic foot than the rich of South Kensington. The precariousness of his income meant landlords felt justified in charging higher rents to cover themselves against inability to pay or moonlight flits – an early example, perhaps, of what is now known as the “poverty premium”.

In 1883 Rev Barnett was able to return to his old university to speak at the Oxford Union, and to win by unanimous vote the motion that “the condition of the poor in our large towns is a national disgrace”. And he found a receptive audience when, in November 1883, he came “as a prophet” to talk to a small group of graduates at St John’s College, Oxford, urging them, as one listener recalled, to “share the life of that dim and strange other world of east London”.

For the Barnetts, this “university settlement”, proposed eight months after Karl Marx’s death, would help show the people demanding something more than liberty that they did not need to go as far as revolution.

“The poor,” Rev Barnett wrote in 1895, “think progress is to be won by revolution.” But he believed projects such as Toynbee Hall could help preach “the good news of a unity greater than rich or poor … Humanity will help the poor see the rich as their brothers, and God as their father.”

Rev Barnett and the forceful, equally accomplished Henrietta hoped the young Oxford men would do in the city something akin to what the gentry was supposed to do in the countryside: befriending the poor and showing them how to lead better, fuller lives. The Barnetts’ vision, however, also contained large doses of humility.

Before devising any bright ideas of their own, the Oxford men were supposed to learn from the poor among whom they were going to live. “The needs of east London are often urged,” Rev Barnett told them, “but they are little understood. He who has, even for a month, shared the life of the poor can never rest again in his old thoughts.”

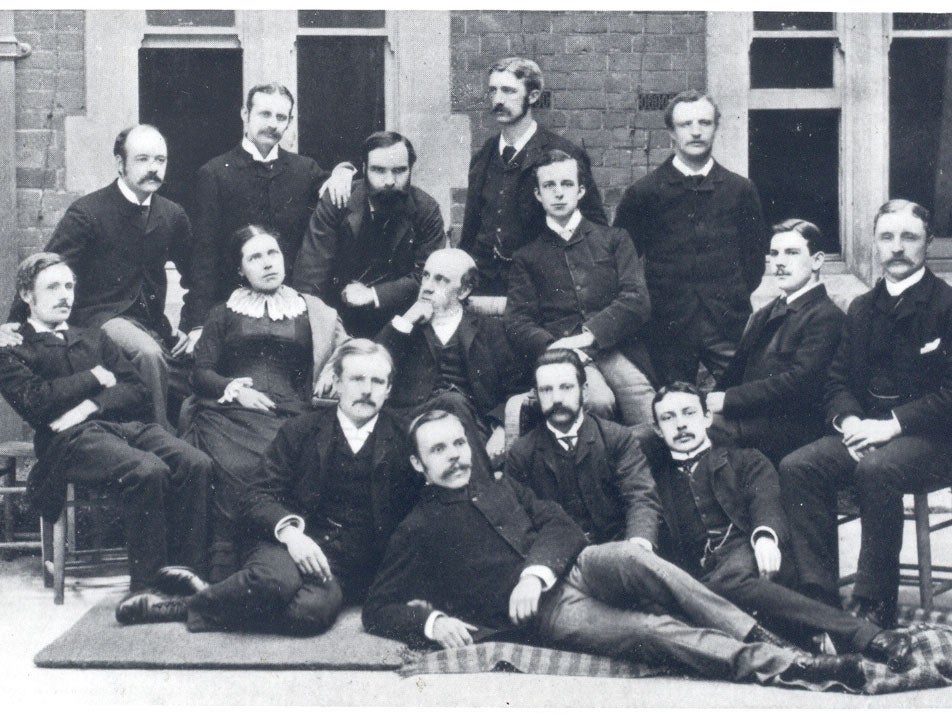

And so began the building, in the heart of the East End, of something resembling an Oxbridge college. Named Toynbee Hall, after the Barnetts’ recently deceased kindred spirit Arnold Toynbee, the Oxford historian credited with coining the term “the Industrial Revolution”, it opened its doors for the first time in 1884.

Rev Barnett was the first warden. The volunteer residents dined in a hall adorned with the crests of their old Oxbridge colleges. They were soon offering help, solidarity and a rather mind-boggling array of activities to the East End.

In one of the most definitive accounts of the early years of Toynbee Hall, Professor Emily Abel described how East End errand boy Ernest Baker found himself assisting in the running of the Toynbee Hall Elizabethan Literary Society.

The Natural History Society broadened East Enders’ horizons by taking them into the countryside, and under the tutelage of some of the more vigorous volunteer residents, the Toynbee Travellers’ Club introduced the London poor to the joys of mountain climbing in the Swiss Alps.

As Prof Abel noted, Toynbee Hall’s early residents did not always avoid being clumsily patronising – one suggested the Shakespeare Club could counteract east Londoners’ “inability to amuse themselves rationally”.

But the smoking debates seem to have been pretty egalitarian. With the men puffing on their pipes to keep everything calm and convivial, it seems every shade of opinion could be, and was heard. In their 1984 book Toynbee Hall, The First Hundred Years, the historians Asa Briggs and Anne Macartney described how in 1902 the Liberal MP John Morley introduced a debate on Our Foreign Policy.

Among those present was a shabbily dressed character who said his name was Richter. In broken English, he berated Morley for supporting the imperialist foreign policy of Britain and other “capitalist nations”.

“Go down to Limehouse or Shadwell and see how the people live,” said Richter. “Their slums, impoverishment, degradation and prostitution! That’s where your foreign policy should lie. They are the victims of your capitalist organisation which is just as powerful and cruel as the force of arms.”

Morley and others politely begged to differ – so politely that Richter was invited back to Toynbee Hall for tea a few days later.

William Bowman, a Toynbee Hall resident who was present at the tea, recalled how Richter, “who seemed hungry”, tucked into the cakes and was particularly fascinated by the buttered muffins, which he had never tried before.

But he wouldn’t budge from his belief in violent revolution.

“History has shown,” he told the Toynbee Hall residents between mouthfuls of cake and muffins, “that no great change has been brought about without the shedding of blood and revolution.”

Eventually he declared: “I have enjoyed this talk, but now my time is up. I must go to visit my friends in Limehouse.”

Richter shook hands with the assembled company and departed. Only much later did the Toynbee Hall residents realise that they had in fact been having tea with the exiled Russian revolutionary Vladimir Lenin.

In a gentler way, some of the stances taken by Toynbee Hall and its residents have been, if not revolutionary, then at least profoundly challenging to conventional wisdom. Even as the hall opened, the Barnetts were in the process of parting ways with the Charity Organisation Society (COS), which had started in 1869 as the Society for Organising Charitable Relief and Repressing Mendicity.

Much emphasis was placed on repressing mendicity – begging. Rather as some now rail against a perceived “benefits culture”, the social reformer Octavia Hill, a driving force in the COS, firmly believed that indiscriminate alms-giving “degraded” the poor, making them happy to rely on charity and unable or unwilling to support themselves through hard work.

In a possible echo of the current debates around fit-to-work benefits tests, it was believed that extensive scrutiny of applications for “relief” was needed to distinguish the virtuous but luckless worker from the “clever pauper”.

“The main tone of action,” maintained Hill, “must be severe. There is much of rebuke and repression needed, although a deep and silent undercurrent of pity may flow beneath.”

Samuel Barnett had once been an enthusiastic proponent of COS views. Henrietta began her career working for Octavia Hill. But to the consternation of the COS, the couple turned against what Samuel Barnett called those who “neglect the fact that wages … cannot provide sufficient income to make a man independent in sickness and old age [and who] demand reform which will make relief impossible for anyone desiring to retain his self-respect.”

In the eyes of the Fabian Beatrice Webb, the Barnetts “discovered that there was a deeper evil than unrestrained charity, namely unrestricted and unregulated capitalism and landlordism.”

And so in 1888 the matchgirls of the East End found allies in Toynbee Hall when they went on strike, protesting against pitiful wages and factory conditions that included white phosphorous fumes destroying jawbones, giving match-makers “phossy-jaw”.

In an early example of Toynbee Hall residents learning from their East End neighbours, a group of them made their own investigations, then helped shape public opinion with letters to The Times detailing the matchgirls’ “deplorable conditions” and below-subsistence wages.

The matchgirls – “these courageous girls [with] neither funds, organisations, nor leaders,” as Fabian socialist Harry Snell called them – won a famous victory. And in 1889 when the dockers went on strike, Rev Barnett himself privately admitted: “My feelings are with the men”.

Five years later he would publicly rebuke those who accused trade unions of putting workers’ self-interest above the good of the country. “The same charge,” he wrote, “could be made [against] capitalists [who] form trusts and provide companies for their own people which raise the price of the necessities of life against workmen.”

After its first warden Samuel Barnett died in 1913, it could be said that Toynbee Hall rose to other challenges. On Sunday 4 October 1936 Oswald Mosley tried to march his uniformed blackshirts through the East End. Jewish groups, trade unionists and leftwingers mobilised to block the fascists’ path with barricades and cries of “They shall not pass!”

When the police tried to clear a route for the British Union of Fascists, the “Battle of Cable Street” began. The fascists did not pass. Defeated by the dogged East Enders, police commissioner Sir Philip Game was forced to tell Mosley to march west, out of the area.

A week later, however, in what became known as the Mile End Pogrom, about 200 fascists smashed up Jewish shops and houses in the Mile End Road, even throwing a young child and elderly Jewish man through a window.

Toynbee Hall warden Jimmy Mallon was appalled. He called a meeting at Toynbee Hall that led to the creation of a Council of Citizens of East London, which then issued a notice to be displayed in shops and workplaces. “Citizens of East London,” the notice warned. “Forces are at work to destroy the common sense and toleration and good humour on which we pride ourselves. We must work against these forces. Boycott provocative demonstrations. Maintain calm and good temper. Stand together for fair play.”

Meanwhile, Jimmy Mallon joined a delegation that persuaded the government of the need for what became the Public Order Act 1936.

It banned the wearing of uniforms for political purposes, as well as enhancing police powers to deal with marches.

Such achievements are, perhaps, one answer to the sour aside of East Ender and future Labour leader George Lansbury, who in 1928 wrote that Toynbee Hall was used as a stepping stone by ambitious young careerists who would eventually claim that: “The interests of the poor were best served by leaving east London to stew in its own juice while they became members of parliament, cabinet ministers, civil servants.”

Had he lived long enough, Lansbury might have added that Toynbee Hall was also used by at least one ex-cabinet minister to forge a new, post-scandal career.

It is often recalled that in 1963, after being caught lying to parliament about his affair with Christine Keeler, John Profumo began a new career washing dishes at Toynbee Hall, rising to become chairman in 1982 and “learning humility” in the process. But it is often forgotten how much Profumo achieved at Toynbee Hall. He raised funds, helped ease overcrowding through involvement in the Toynbee Housing Association, and backed potentially controversial schemes like the “Grendon outpost”, providing aftercare for former psychiatric-prison inmates.

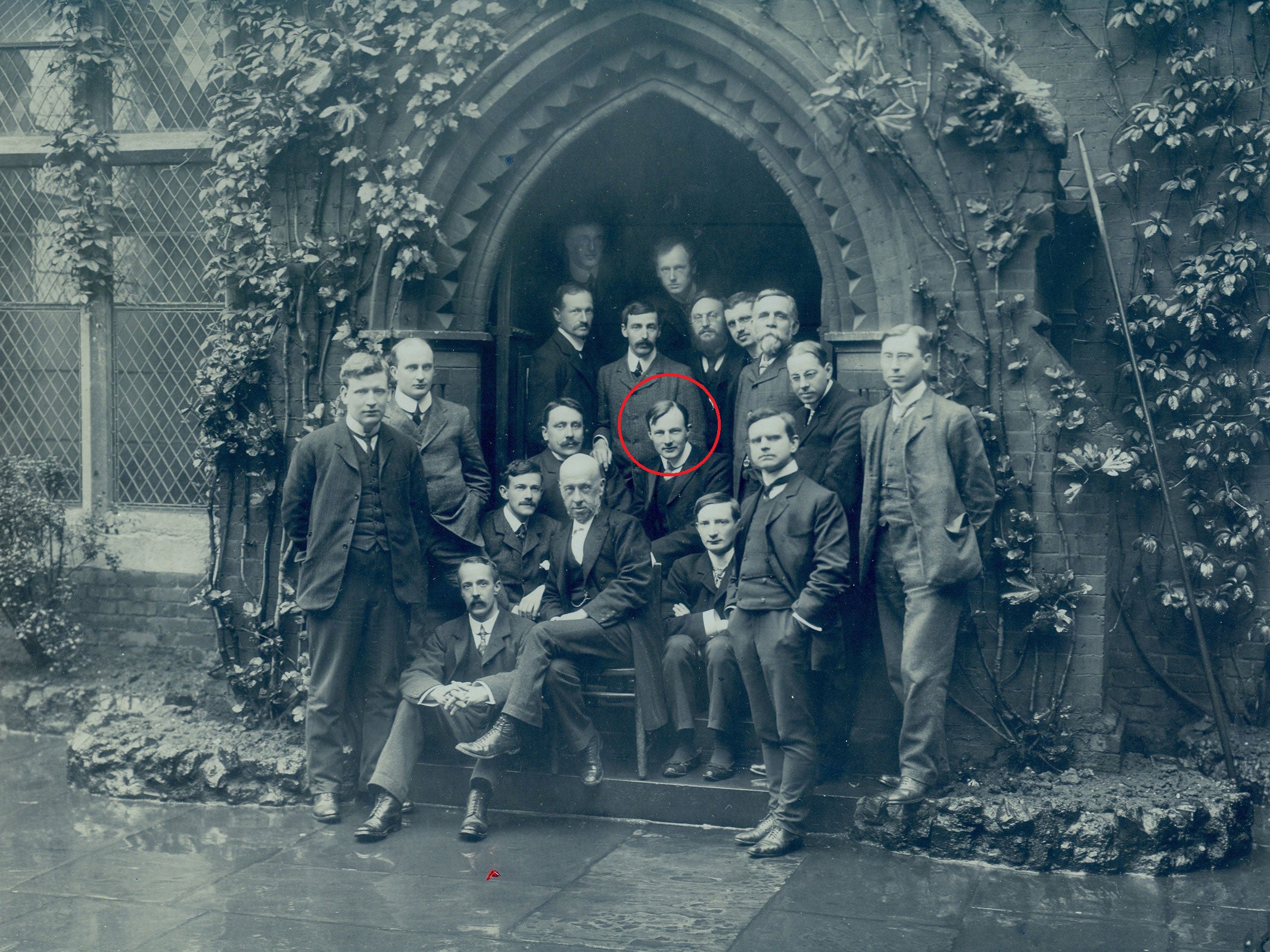

In what could have been another riposte to George Lansbury, William Beveridge freely acknowledged that his coming to Toynbee Hall, aged 24, in 1903 had been the stepping stone to other things. But in the same breath, he said that none of his later achievements would have been possible without the “special knowledge … gained in Whitechapel”.

During his two years at Toynbee Hall, Beveridge was able, he later recalled, “to learn about the main economic problem of those days, not from books, but by interviewing unemployed applicants for relief”.

Beveridge, who arrived in Whitechapel telling his father he had “a vision of Toynbee [Hall] speaking one day with a voice of thunder,” would go on to write the 1942 report that became the blueprint for Britain’s welfare state, with its NHS and “cradle-to-grave” social security.

And Beveridge’s recommendations were implemented by the post-war government of fellow Toynbee alumnus Clement Attlee, who spent a year as the hall’s secretary in 1910. Attlee came to Toynbee Hall with prior experience of the East End, having been the manager of Stepney Boys’ Club and an assistant to Beatrice Webb.

In his 1920 book Social Worker, the Oxford-educated former public schoolboy revealed some of the lessons the East End had taught him.

Attlee wrote:

I met a small boy in the street one day.

“Where are you off to?” said he.

“I’m going home to tea,” said I.

“Oh, I’m going home to see if there is any tea,” was his reply.

Echoing the Barnetts’ growing distaste for the COS, while seemingly anticipating some of the thinking behind – and modern arguments about – the welfare state, Attlee inveighed against “the suggestion that those in need of relief should be passed through a sort of sieve”

“A right established by law, such as that to an old-age pension,” he suggested, would involve less “loss of dignity” than “a [charitable] allowance made by a rich man to a poor one dependent on his view of the recipient’s character and terminable at his caprice.”

And talking about caprice, he added: “The very people who object to the law being used to prevent sweated wages or high rents will [say that] the purchase of a piano by a working man outrages their sense of what is fitting.

“They will spend much time finding ways in which small wages may be made to go a long way, without considering whether those wages should not be raised, or recognising that the claim to a share in the better things of life which is expressed in the purchase of luxuries is a more hopeful thing than submission to low wages.”

In the newly restored Toynbee Hall, Jim Minton expresses pride in the connection to men like Attlee and Beveridge. But he is careful to temper such pride with a recognition of the work still to be done.

Despite 134 years of “progress”, despite the wealth represented by those gleaming City of London towers, the East End – still – contains two of the three worst-rated UK parliamentary constituencies for child poverty. And in 2015, the last time such official statistics were compiled, the east London boroughs of Tower Hamlets, Hackney and Newham were ranked the worst local authority areas in the country for income-deprivation among older people.

Tower Hamlets, Toynbee Hall’s local borough, has about 2,000 homeless families in temporary accommodation and in 2015 just over a quarter of its population was found to be living in income deprivation.

“We are talking every day to people who have financial problems,” says Minton. “There are still huge amounts of poverty in east London.

“The learning process that Attlee and Beveridge and hundreds of other less famous people would have gone through at Toynbee Hall,” says Minton, “would have been about challenging, and saying: ‘This is unacceptable. Why is this happening, and what can we do about it?’”

“That,” he declares, “is very much the spirit we want to keep alive.”

‘Toynbee Hall: A Powerhouse for Social Change’ is open Monday-Friday and on the third weekend of every month at Toynbee Hall, 28 Commercial Street, London, E1 6LS

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments