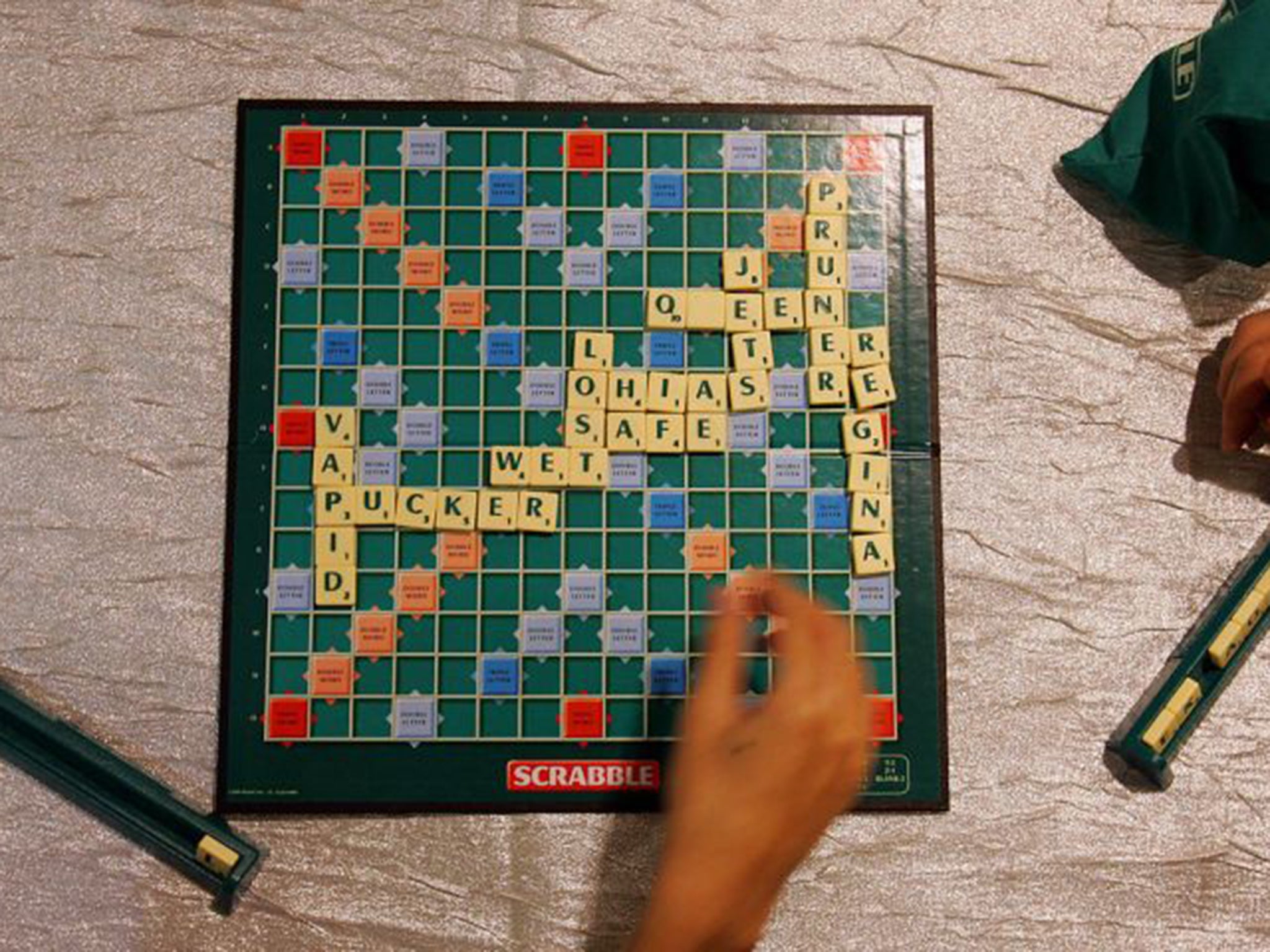

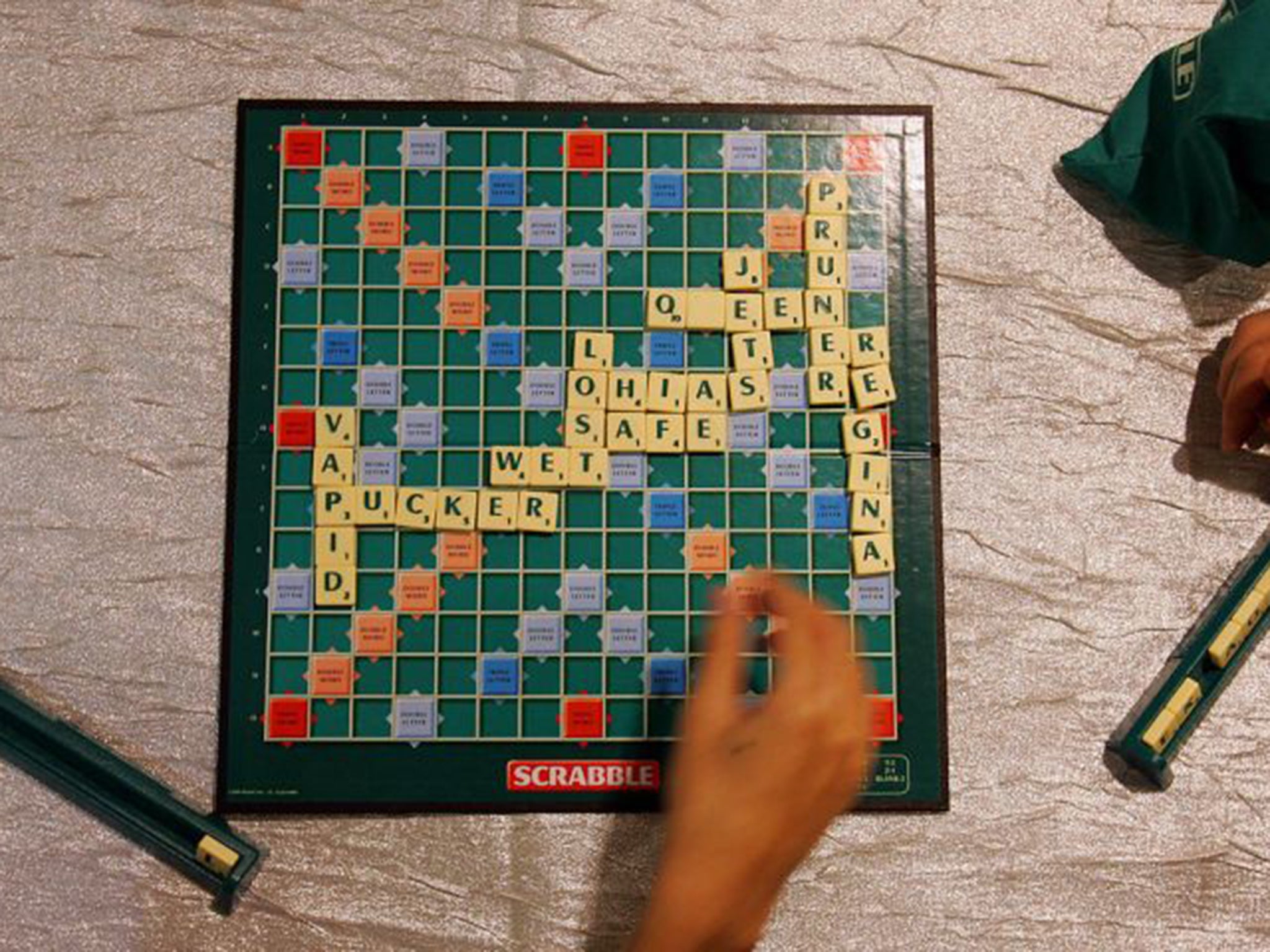

The UK National Scrabble Championship is not for the faint-hearted

Some of the hardest words are not the ones on the board

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.A hush descends upon Scrabble’s Theatre of Dreams: Orchard Suite 2 at the Holiday Inn, Milton Keynes. The UK National Scrabble Championship begins.

The only sound is the occasional rattle of a bag of Scrabble tiles as a player picks out their next letters.

A middle-aged lady in a cardigan peers intently through her spectacles and writes her latest move into her scorebook.

I have already been warned: this could get feisty.

Steve Perry, 66, the chairman of the Association of British Scrabble Players, the tournament’s governing body, told me: “This will be the first major British tournament played to the new dictionary: Collins Official Scrabble Words 15.”

The book lists 276,663 allowed words, 6,000 of them new, and Mr Perry confidently predicted: “There are going to be many challenges, with players contesting what their opponent has put down.”

Two days of contest, 52 contenders seeking the £1,000 first prize, and a game nicknamed Squabble even before the new dictionary stirred things up: they had chosen Peter Thorpe, their tournament director, wisely. His other game is rugby. He plays prop forward.

“I once had to report a respectable middle-aged lady for palming tiles,” said Mr Thorpe, 51, of Gravesend. “I have seen people pulling their hair out and banging the table…”

Other players whispered of tantrums, overturned boards and a “catfight” between two grey-haired ladies at the British Matchplay Championship some years ago.

Even the big beasts suffer. Mark Nyman, 48, of Knutsford, Cheshire, the 1993 Scrabble World Champion, lost the key game of the 1999 world final by one point. “I was mentally destroyed,” he said. “I lost sleep for a year.”

As predicted, on the third game the new dictionary produced its first disturbance. Donna Stanton, a social worker from Manchester, used a blank tile as an R to make “relined”, the N sitting next to a U and a G already on the board to form the newly permissible “nug” (a chunk of wood sawn from a log).

But she was fretting so much about whether nug really was allowed that she absent-mindedly circled the letter N instead of R on her competition card when recording how she had used her blank tile.

Her opponent challenged. Mr Thorpe had no choice but to apply the letter of the law and reduce Ms Stanton’s score for that turn from a game-changing 74 to zero.

After apologising to Mr Thorpe for snapping at him, she spent the lunch break fuming about embracing the spirit of the game, not just the technicalities.

“I could have been up there with the big boys,” she said. “I could have had three wins out of three…”

She was so stressed, she initially gave her age as 51, not 50.

But there was no angst about what these new words represent: a world that accepts “wuz”, “lolz”, “lotsa” and “thanx”. It might have been End of Days for English teachers. It wasn’t for players in Orchard Suite 2.

“Nobody cares,” said Ms Stanton, after making peace with her opponent, “as long as we can get it on a Scrabble board.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments