The private thoughts of Dr Livingstone, I presume

Historians decipher Scottish explorer's letters from deepest Africa

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.In the eyes of his fellow Victorians, Dr David Livingstone was a swashbuckling explorer; a man fuelled by missionary zeal who bravely trekked through vast swathes of central Africa in search of the source of the Nile.

When his body was returned to Britain following his death from malaria in 1873, he was hailed as a hero and was even given a state burial in Westminster Abbey.

Most of what we know about Livingstone's final years emanate from his friend and biographer Horace Waller, who carefully censored the doctor's letters to portray him as a heroic and saintly martyr.

But now an international team of historians and scientists have started unlocking his final letters, in a project they hope will provide a definitive account of the famous explorer's state of mind during his final years in Africa.

For the past 140 years, most of Livingstone's manuscripts and private thoughts have been indecipherable because of the circumstances in which they were written. The Scottish-born physician's final expedition to look for the source of the Nile in what is now the Democratic Republic of Congo was cursed by problems from the outset. Supplies were short and Livingstone was forced to write many of his observations in the margins of torn out pages from books and scraps of newspaper, using ink made from berries – which subsequently faded.

But by using advanced imaging technology, academics have managed to retrieve a large portion of Livingstone's precious words. Scientists at UCLA in California have been using mutli-spectral imaging to peer through the separate layers of each page and rebuild what he wrote. Historians at Birkbeck, University of London, meanwhile, have started to transcribe the data from UCLA to recreate the doctor's letters, which they hope to eventually publish online in full. Their task has been somewhat complicated by Livingstone's erratic method of writing, which weaves an unsteady course around the margins of the page before meandering vertically across the horizontal print of the books he reused.

The first deconstructed letter was written by Livingstone in 1871 from the village of Bambarre, where the explorer was held as a virtual prisoner. Written to his friend Waller, it provides an insight into the state of his mind as he lay thousands of miles from home, wracked with disease and still no closer to finding the Nile's source.

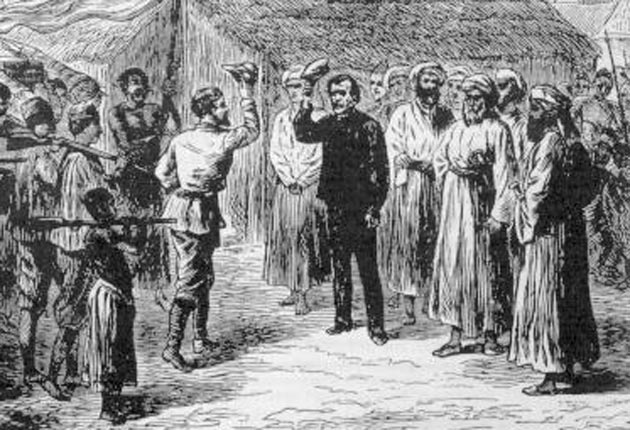

Livingstone, it seems, was keen to make sure that the press in Britain were kept in the dark about his failing health. "I am terribly knocked up but this is for your own eye only," he wrote to Waller in the letter. "[Am] in my second childhood [referring to his lack of teeth – several of which he extracted himself] a dreadful old fogie. Doubtful I'll ever see you again." In the same letter he also railed against slavery, something which Livingstone grew to abhor the more he travelled around Africa. Historians believe the missive only arrived in Britain after Livingstone's death and was carried by Henry Stanley, the reporter who tracked down the doctor with the (now disputed) words: "Dr Livingstone, I presume?" Dr Debbie Harrison, the project's contributing editor, said: "His closing line to Waller indicates Livingstone's anxious and depressed state of mind. He did not know that in just a few months Stanley would arrive, bringing desperately needed food, medicines and the longed-for news from an outside world he thought had forgotten him."

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments