The Mitrokhin archive: KGB defector's copied files reveal Soviet dismay at ‘constantly drunk’ Guy Burgess

Soviet defector’s newly opened collection names KGB spies – but one remains a secret

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

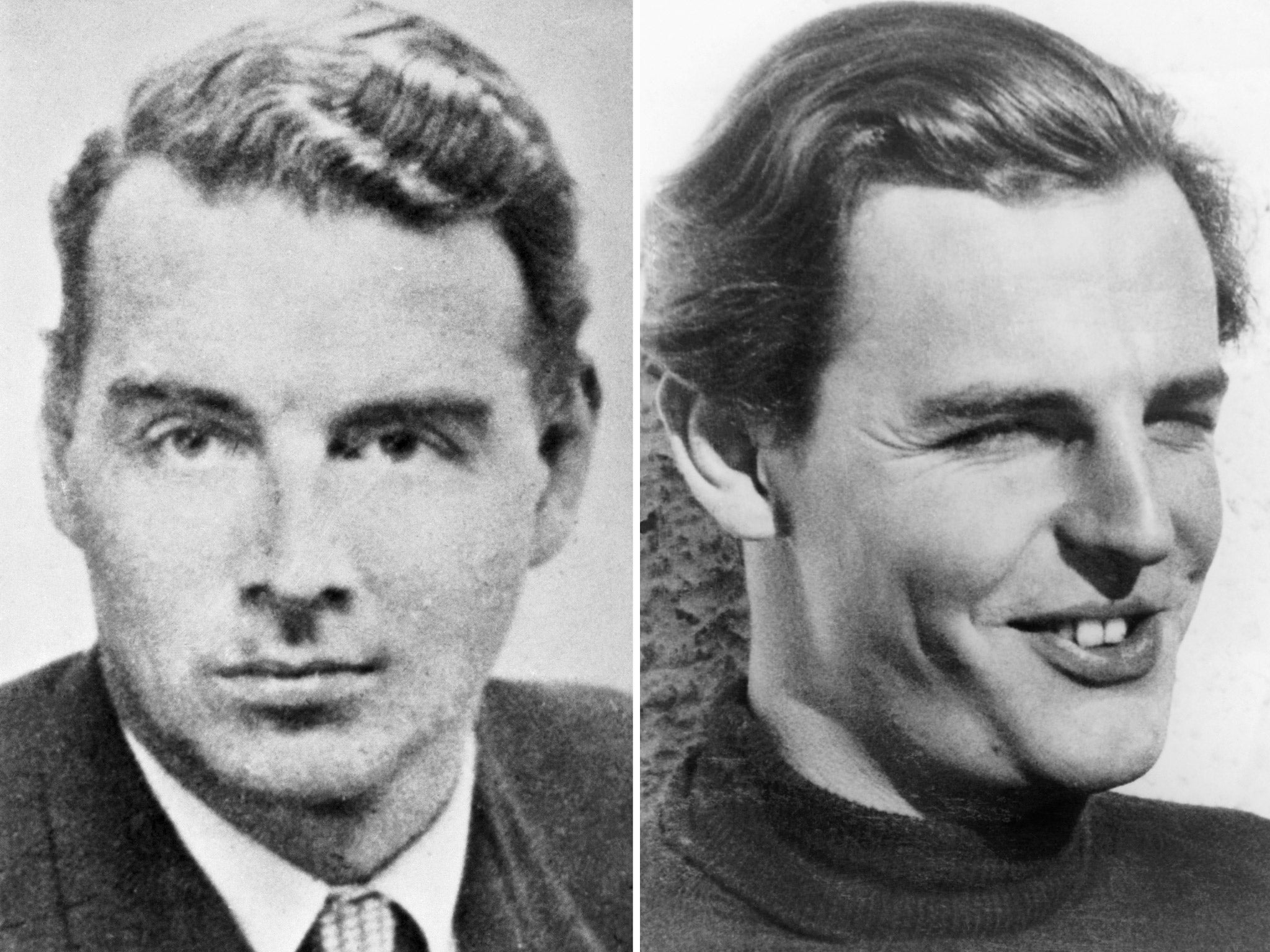

Your support makes all the difference.They were two of Britain’s most notorious double agents, responsible for passing on some of this country’s most sensitive secrets to the Russians, but documents reveal that Guy Burgess and Donald Maclean were viewed in an unflattering light by their Soviet masters.

Among thousands of typed Russian documents in the Mitrokhin archive, open to public inspection for the first time this week, they describe how Burgess, who was “constantly drunk”, horrified his KGB controllers by staggering out of a pub one evening and dropping stolen Foreign Office documents on the pavement. Moscow was also kept informed about Donald Maclean’s alcoholic binges and loose tongue.

It emerges that the spy they valued most was the remarkable Melita Norwood, nicknamed “The Spy Who Came in From the Co-op”, who died in 2005 aged 93. She was never prosecuted and would never have been exposed but for the archive of Vasili Mitrokhin, a senior officer in the Soviet political police who brought the documents to Britain after he defected.

When she was uncovered in 1999, she was living quietly in Bexleyheath and flatly refused to apologise for her past. From 1937 to 1971, she passed to the Soviet Union information she picked up as the personal assistant to the head of the British Association for Non-Ferrous Metals Research, which was working on nuclear technology. For 11 years, the Soviets paid her £20 a month. They offered to reward her when she visited the USSR in 1979, but she declined.

Another exceptionally valuable spy kept so well out of sight that his or her name is still unknown.

Russia possesses an amazing collection believed to contain every Foreign Office cable sent to or from any major British embassy between 1924 and 1936. The Mitrokhin archive reveals they were passed to Soviet intelligence by an unnamed cipher clerk working in the Rome embassy.

There is also a wealth of documents denouncing Cardinal Karol Wojtyla, the future Pope John Paul II, as a dangerous anti-communist. Other documents reveal the immense number of agents the KGB put into the field to destabilise the Czechoslovak communist leadership in 1968 during the Prague Spring, when for the first time people living under communism enjoyed the right of free speech.

Other documents – which can be inspected at the Archive Centre at Churchill College, Cambridge – show evidence that Dick Clements, who worked for Labour leaders Michael Foot and Neil Kinnock, was in the pay of the Soviet secret service.

Dick Clements was editor of Tribune from 1961 until 1982, when Michael Foot invited him to move to Labour Party headquarters to run the leader’s private office. He was retained as executive officer when Neil Kinnock succeeded Foot, until 1987. The document says that “Dan” was Tribune’s “editor” (redaktor in Russian).

Clements admitted meeting Soviet officials but denied they had influenced Tribune’s editorial line. He laughed off the idea that he might have been “Agent Dan”.

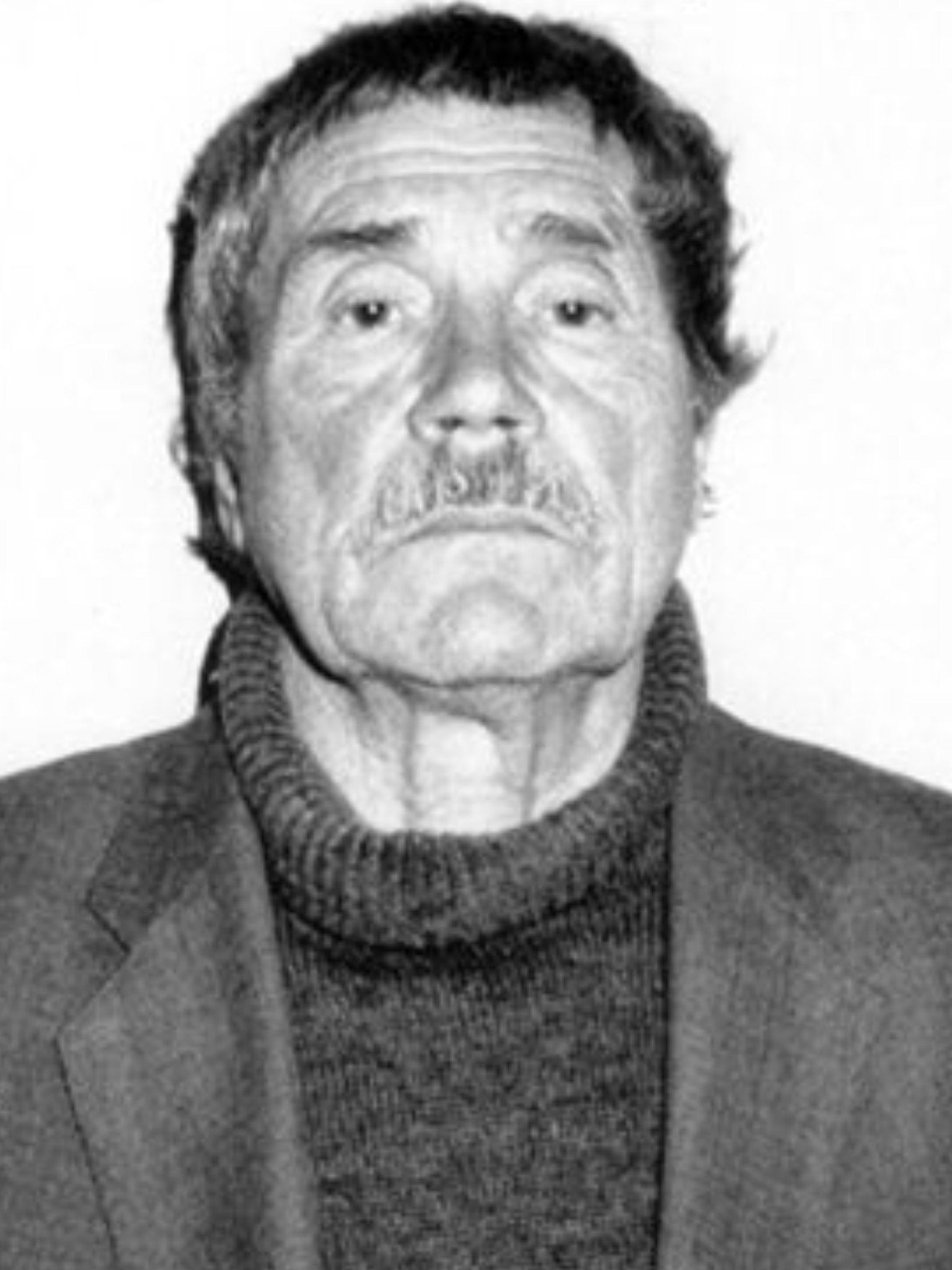

But the most remarkable story relating to the documents is Vasili Mitrokhin’s own.

In 1972, the KGB decided to rehouse its vast archive and Mitrokhin was, for 12 years, the officer responsible for transferring the documents from the Lubyanka to their new location. As he catalogued them, he meticulously copied them out by hand into little green-lined school exercise books.

He retired in 1984, aged 62, wanting this vast treasure trove preserved, but not knowing how he could smuggle it out of the USSR. When the Soviet Union fell apart in 1991 the Baltic states broke free of Russian control, but the usual tight border controls were not yet in place.

Mitrokhin travelled to one of the Baltic capitals – probably Riga – carrying a bag that contained documents hidden under dirty underwear. He deliberately looked shabby to avoid attracting the curiosity of border guards. Having failed to get anyone to listen to him at the US embassy, he visited the British embassy where member of staff offered him a cup of tea and took the documents to be examined by experts. British intelligence quickly discovered they had landed what the FBI later described as “the most complete and extensive intelligence ever received from any source”.

The documents belong to Mitrokhin’s family, who live in the UK, though no one but a select few know where or under what name.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments