The demise of blue plaques: it's not about just bricks and mortar

As budget cuts look set to bring an end to London’s Blue Plaques, Jerome Taylor laments the demise of a cultural landmark

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.There’s something both deliciously ironic and fitting that the earliest surviving commemorative blue plaque – a tradition that is as synonymous with London as beefeaters and black cabs – is for a Frenchman. Years before Napoleon III became the last emperor of France he lived a life of temporary exile in a house on the appropriately named King Street in St James’ where he plotted his eventual return across the Channel.

London – that most international of capitals – has played host to multiple troubled monarchs over the centuries and you don’t need to dive into books to unearth such historical gems. Hit the streets, look up and blue plaques will take you on a fascinating historical tour entirely free of charge.

As the sculptor Sir William Reid Dick, who is himself commemorated in a plaque, put it in 1953: “Buildings are… more than just bricks and mortar: they are the theatres in which our lives are enacted.”

Now the scheme which began a trend that has been copied around the country and the wider world looks set to end thanks to government cuts. English Heritage, the latest conservation group to run the official blue plaque scheme in London, says it will be forced to abandon putting up any new plaques after 2014 because their annual budget has been slashed from £130m to £92m.

Unless a new body – or a new system – is found to take over from English Heritage, a 145-year-old tradition which weathered two world wars and multiple recessions will be no more.

It wasn’t until 1867 that the first circular plaque went up when the Royal Society of Arts chose to pay tribute to Lord Byron’s home on Holles Street.

Byron’s marker was brown because the copper needed to create a blue glaze was considered prohibitively expensive. The plaque was demolished just a few years later when the poet’s house was pulled down. But the trend soon caught on. Napoleon III was the next marker to go up and still survives to this day.

Fast forward to the 21st century and any visitor to London can explore more than 850 plaques commemorating a smorgasbord of the great and the good who made Britain’s capital the world famous city it is today. Type in any postcode into English Heritage’s search engine and you are soon presented with a dizzying array of ghosts to uncover.

Within a one-mile radius of The Independent’s offices off Kensington High Street, for example, there are an astonishing 288 plaques commemorating characters as varied as the libertarian J S Mill, the author William Thackeray, Norway’s king in exile during the Second World War, Haakon VII, John Lennon and the wonderfully named Cetshwayo kaMpande, a Zulu monarch who once delivered a crushing military blow to British forces in South Africa and later lived out a quiet retirement in Holland Park.

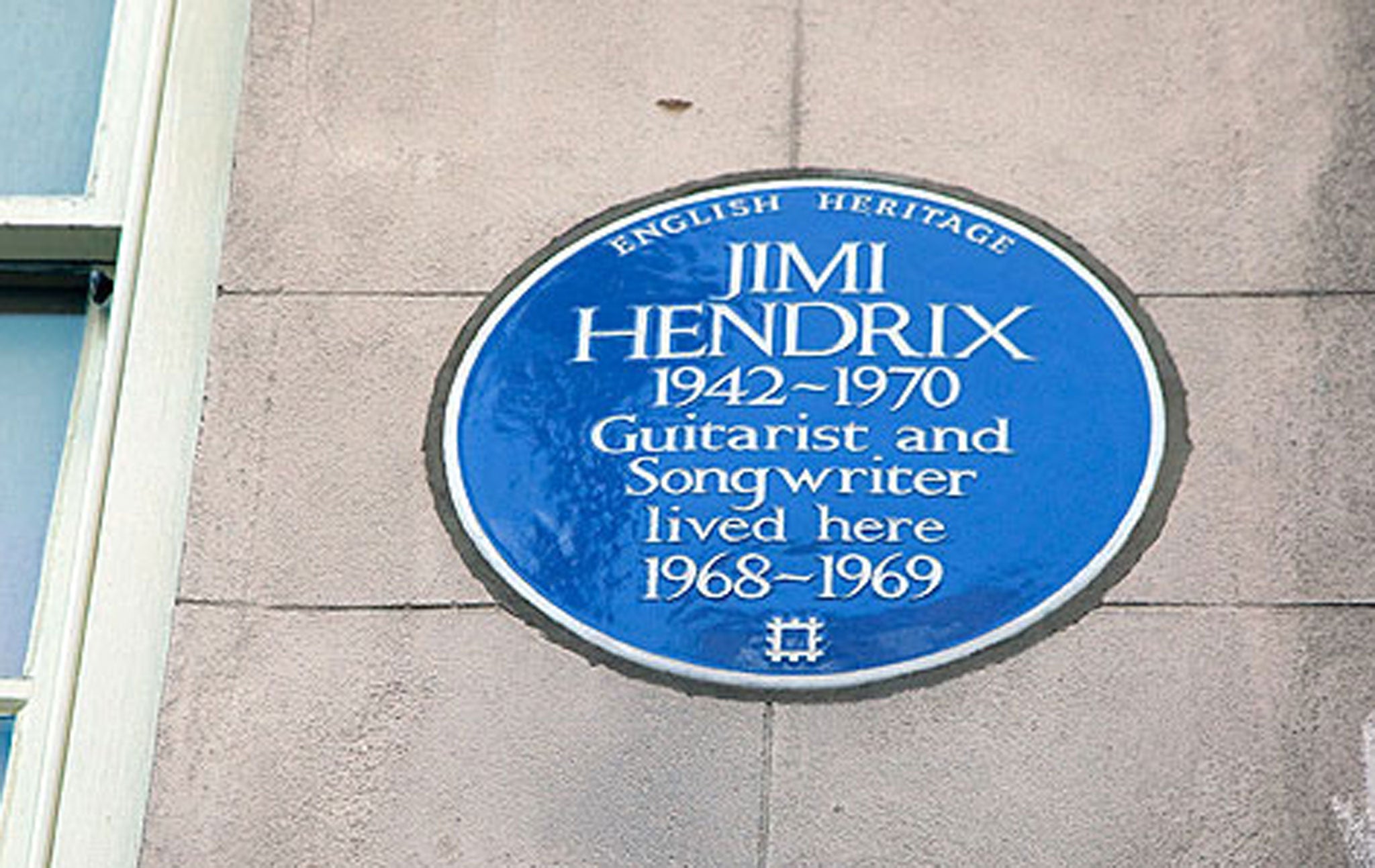

Some streets even have multiple plaques – Brook Street in Mayfair has plaques next to each other celebrating two musical maestros from two very different ages: Jimi Hendrix and George Frideric Handel.

At the turn of the 20th century, the Royal Society or Arts handed over responsibility for the blue plaques to the London County Council until that was subsumed by the Greater London Council. English Heritage took over in 1986 and has employed a panel of historical experts to decide who should be commemorated.

Apart from a brief pilot scheme to expand it in the late 1990s the original blue plaque scheme has always been London-focused but local authorities and conservation groups up and down the country have all come up with their own variations. Historical markers have also cropped up in Europe, North American and Australia.

Under the rules governing the original scheme, candidates are submitted by members of the public and must either be dead for at least 20 years or approaching the centenary of their birth. The plaques can only be placed on a building that has a direct connection to the famous figure.

The current panel of experts, which currently includes luminaries such as Stephen Fry, Bonnie Greer and the Poet Laureate, Andrew Motion, has been disbanded in the wake of budget cuts.

The decisions made over the decades have not been without controversy – Edward VII’s lover Wallis Simpson, the Scientology founder, L Ron Hubbard, and The Who drummer, Keith Moon, are just three recent examples of famous figures whose rejection has caused rows.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments