The Big Question: What is legal aid and should we be providing so much of it?

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Why are we asking this now?

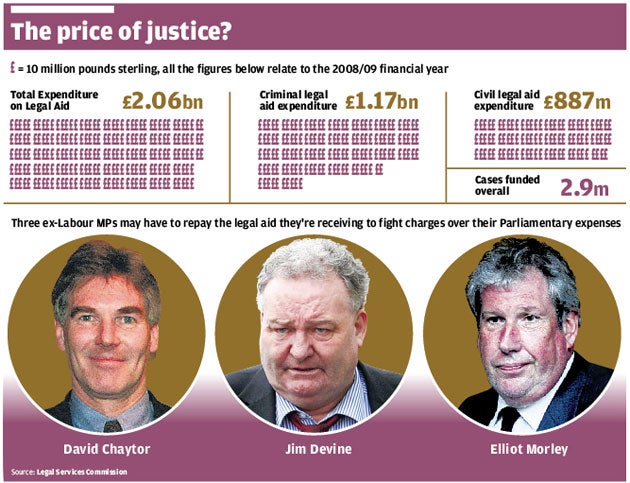

On Monday, it was announced that three former Labour MPs – David Chaytor, Jim Devine and Elliot Morley – had won the right to receive legal aid to fight charges of false accounting relating to their parliamentary expenses. The news thrust MPs' expenses back into the spotlight and did no favours to the legal aid system, so often the butt of politicians' ire.

David Cameron denounced the move as an "outrage" and pledged yet another review of the legal aid system if the Tories win the election. He said the outcome of a review could not be prejudged but it would definitely mean "there won't be legal aid available for MPs who accused of fiddling their expenses".

Why is legal aid such a popular target?

The animus some feel against legal aid is part of a wider phenomenon; a broad suspicion – which all parties tend to indulge for populist reasons – that criminals have too easy a life because liberal judges and lawyers have weighted the criminal justice system in their favour, against the interests of victims of crime.

The idea that £2bn of public money is given each year to defendants, some of whom are charged with heinous crimes, strikes some sections of the public as offensive. The fact that the radical Islamic cleric, Abu Hamza, ran up a whopping legal aid bill while fighting terrorism charges a few years ago did not exactly make legal aid more popular.

So that was a disgrace then?

Not necessarily. Abu Hamza was as entitled to receive legal aid as anyone else, as are the former MPs accused of fiddling their expenses. Whether the politicians should have decided to seek legal aid is another matter. The system of paying for people to be defended in court when they cannot afford their own lawyers, which dates back to the welfare state reforms of the 1940s, does not judge the recipients of the aid on the grounds of whether they are particularly nice or sympathetic; the question is whether they can afford a court case.

Andrew Katzen, a lawyer from Hickman and Rose, a firm which specialises in legal aid cases, stresses that "it should apply especially to people accused of serious and high-profile cases as the interests of society are best served if they are well rather than poorly represented." What complainants about legal aid fail to realise (partly because politicians have no interest in pointing it out) is that however annoying it may be to think of public money going to so-called "hate preachers", for example, were these people forced to defend themselves their cases might drag on ad infinitum. This would probably cost the public purse far more than it would were they to have a lawyer. Justice would also be ill-served by people having to defend themselves in court when they were manifestly not capable or trained to do so.

So the system needs no reform then?

Politicians' easy rants against the system aside, numerous things have gone wrong. As the number of court cases has ballooned vastly over the years, legal aid has cost more. Various reforms have been imposed – usually at the behest of governments wanting to tighten up loopholes and cut costs. But these changes have created such a confusing mishmash of rules about who is eligible for legal aid that even lawyers specialising in the field have a hard time working them out. One problem is that piecemeal reforms intended to "simplify" matters rarely function in the manner intended. Partially replacing means-testing with criteria based also on the severity of the crime have just made the system more confusing than ever.

The latest reforms to legal aid, now being phased in and piloted in certain parts of the country, result in a broadly two-tier system. In magistrates' courts in the pilot areas, legal aid is decided on the basis of the merit or severity of the case. If a defendant passes that, a means test follows, based on his or her income. In higher courts, eligibility for legal aid also depends on first passing a merit test and, if the case is deemed sufficiently severe, a defendant may receive aid. But at the end of the case, he or she may have to pay back some costs from his or her capital. However, it is not certain whether the ex-Labour MPs involved in the expenses case will have to repay their legal aid. Gordon Brown has indicated that they will – but their case is not being heard by one of the courts involved in the pilot scheme. When the Prime Minister's spokesman was asked to clarify his comments, it was significant that he emphasised the likelihood of them repaying the money as a result of public pressure, not because they were legally bound to do so.

Anything else wrong?

Plenty. A tiny percentage of cases consumes a disproportionate proportion of the annual legal aid budget, limiting the money available for the huge majority of cases. And because lawyers are now paid fixed fees rather than by the hour, fewer highly qualified law firms wish to undertake such cases, resulting in more work going to lawyers who are poorly trained, or who do not charge much money – for a good reason.

What can we do to reduce this muddle?

There could be better quality control. Too many law firms are out there touting for the work and not all of them offer the best value for money. If quality standards were raised, the number of providers could be reduced and the service improved at the same time. It would be possible to weed out the less skilled, poor performing lawyers and get a smaller group of legal experts doing the work more efficiently. Another reform could involve the so-called "very high cost" cases which, though few in number, consume such a huge amount of the legal aid budget. In theory, the management of these cases, including costs, is assessed by civil servants but in practice this does not happen. Tighter assessment of costly cases is needed; that way the money could be shared out more fairly and go further.

Will any of this happen?

Labour has said it intends to cut the number of firms able to undertake legal aid, tightening standards and at the same time cutting costs. But legal aid is all too often a "Cinderella issue" – the instinct of most politicians is to ignore it most of the time, and then lay into it with a fury when public anger is roused.

The worry is that, while the temptation has always been to cut, and while the cost should certainly not be allowed to rise indefinitely, it could end up being decimated as part of some broader package of spending cuts to popular, "wasteful" services. That might be a vote- grabber in the short term. But in the long term, it is far from clear that much money would be saved, and justice would certainly suffer.

Is it time this entitlement was drastically cut?

Yes...

* The cost has ballooned from £1.5bn in the mid-1990s to more than £2bn now

* The main beneficiaries of this exponential growth over the years have been lawyers

* Indiscriminately allowing so many people to get legal aid brings the justice system into disrepute

No...

* It is not legal aid that is the root problem but the vast increase in court cases

* The biggest victims of cuts to legal aid won't be lawyers but poor and middle-income defendants

* Targeted reforms rather than knee-jerk reactions could answer complaints levelled at the system

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments